When someone hears "inflammatory bowel disease," they might think it’s just one condition. But it’s not. It’s two very different diseases that look similar on the surface but behave in completely different ways. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis both cause chronic gut inflammation, pain, and fatigue - but where they strike, how deep they go, and how they respond to treatment? Those differences change everything.

Where the Inflammation Lives

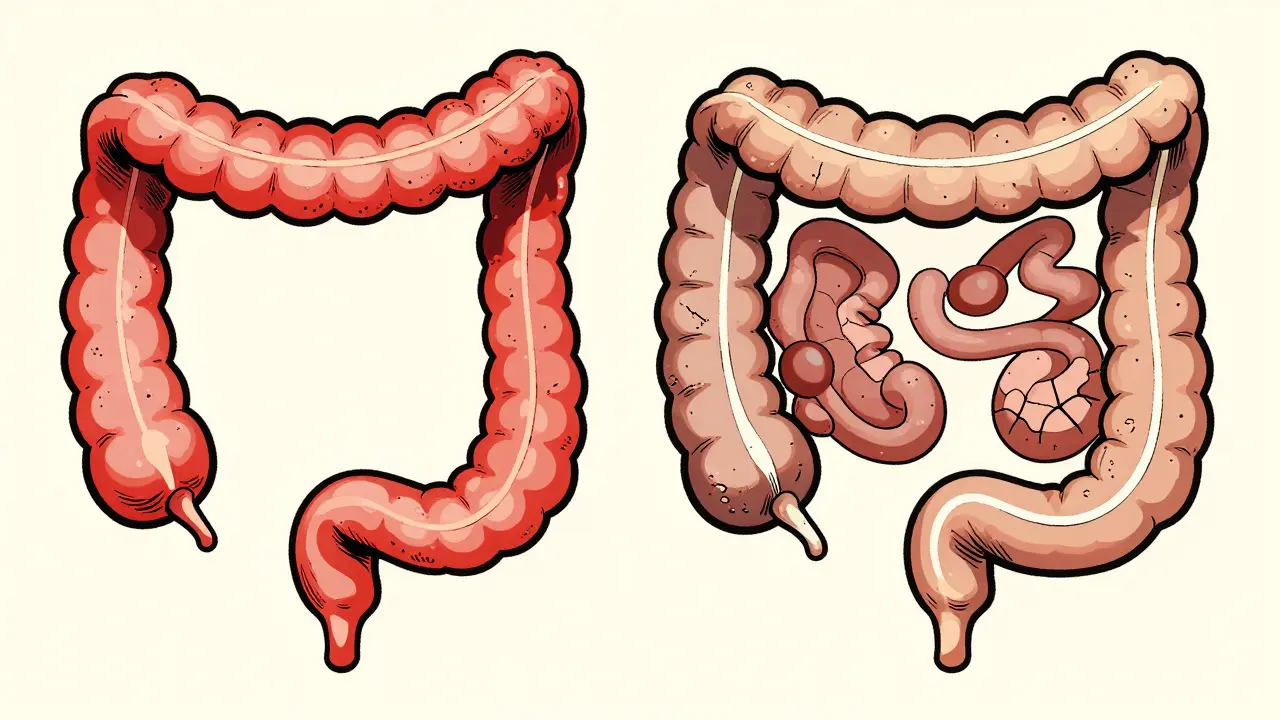

- Ulcerative colitis (UC) sticks to one place: the colon and rectum. It starts at the rectum and creeps upward in a continuous line, like a tide moving through the large intestine. If you have UC, your small intestine, stomach, and even your mouth are untouched.

- Crohn’s disease doesn’t care where it shows up. It can hit anywhere from your mouth to your anus. Most often, it lands in the last part of the small intestine (the terminal ileum) or the beginning of the colon. But it can skip around. One patch of your intestine might be destroyed, the next one healthy, then another wrecked. These are called "skip lesions," and they’re a dead giveaway for Crohn’s.

This isn’t just a detail - it’s the core of how doctors tell them apart. A colonoscopy will show continuous redness and ulcers in UC. In Crohn’s, you’ll see patchy inflamed areas with healthy tissue in between, sometimes with a cobblestone look from deep cracks in the lining.

How Deep Does It Go?

- Ulcerative colitis stays shallow. It only eats away at the innermost layer of the bowel wall - the mucosa. Sometimes it reaches the next layer down (submucosa), but that’s it.

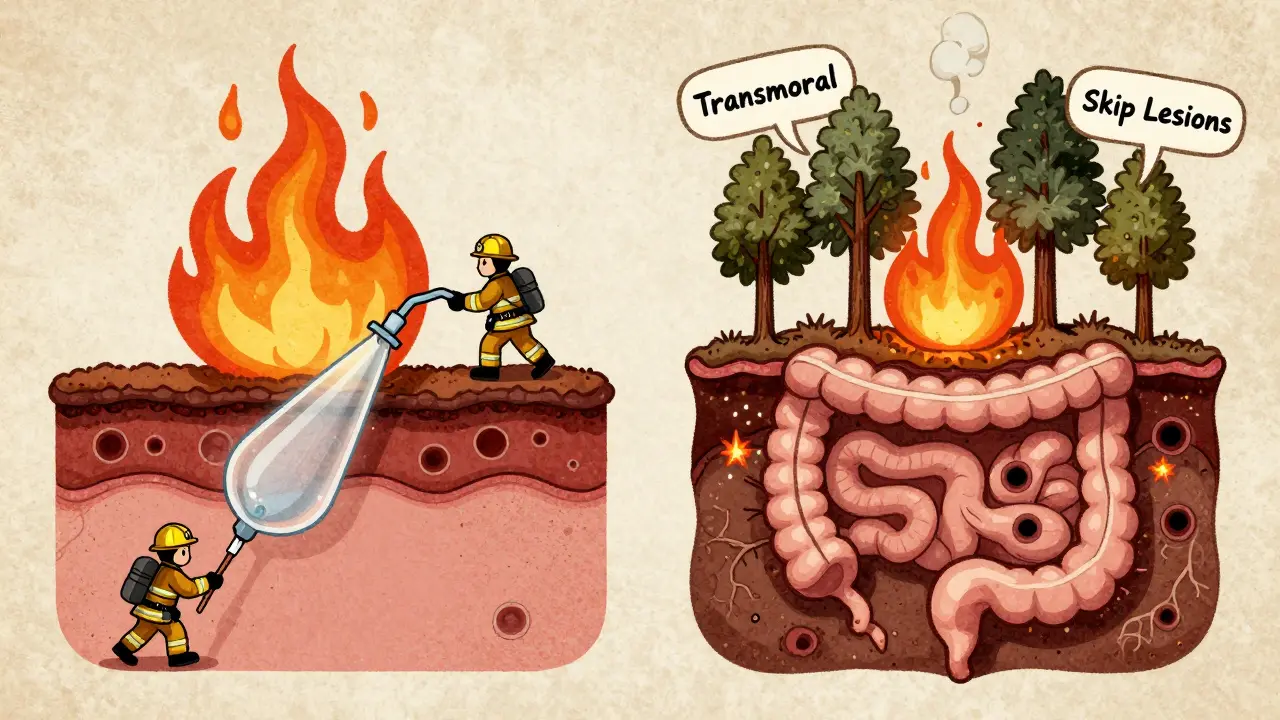

- Crohn’s disease goes all the way through. It’s transmural. That means it punches through every layer: mucosa, submucosa, muscle, and even the outer covering (serosa). This is why Crohn’s patients are at risk for fistulas - tunnels that form between loops of intestine, or between the bowel and bladder, skin, or vagina.

Think of it like a fire. UC is a brush fire that burns the surface. Crohn’s is a wildfire that burns through the roots, the soil, and the trees beneath. That’s why Crohn’s can cause abscesses, strictures (narrowing from scar tissue), and perforations. UC rarely does.

Complications: What You’re Really Up Against

Both diseases can lead to weight loss, fatigue, and anemia. But their big dangers are different.

- Crohn’s patients have a 1 in 3 chance of developing strictures over their lifetime. About 1 in 4 will get a fistula. These complications often need surgery - and even then, the disease comes back. About half of Crohn’s patients need a second surgery within 10 years.

- Ulcerative colitis rarely causes fistulas or strictures. But it can trigger toxic megacolon - a life-threatening swelling of the colon during severe flares. It happens in about 5% of UC cases. This is rare in Crohn’s.

Outside the gut, both can cause joint pain, skin rashes, and eye inflammation. But one condition has a special link: primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a liver disease. Around 3 to 7% of UC patients develop it. For Crohn’s patients? Less than 1%. If you have PSC, you’re far more likely to have ulcerative colitis.

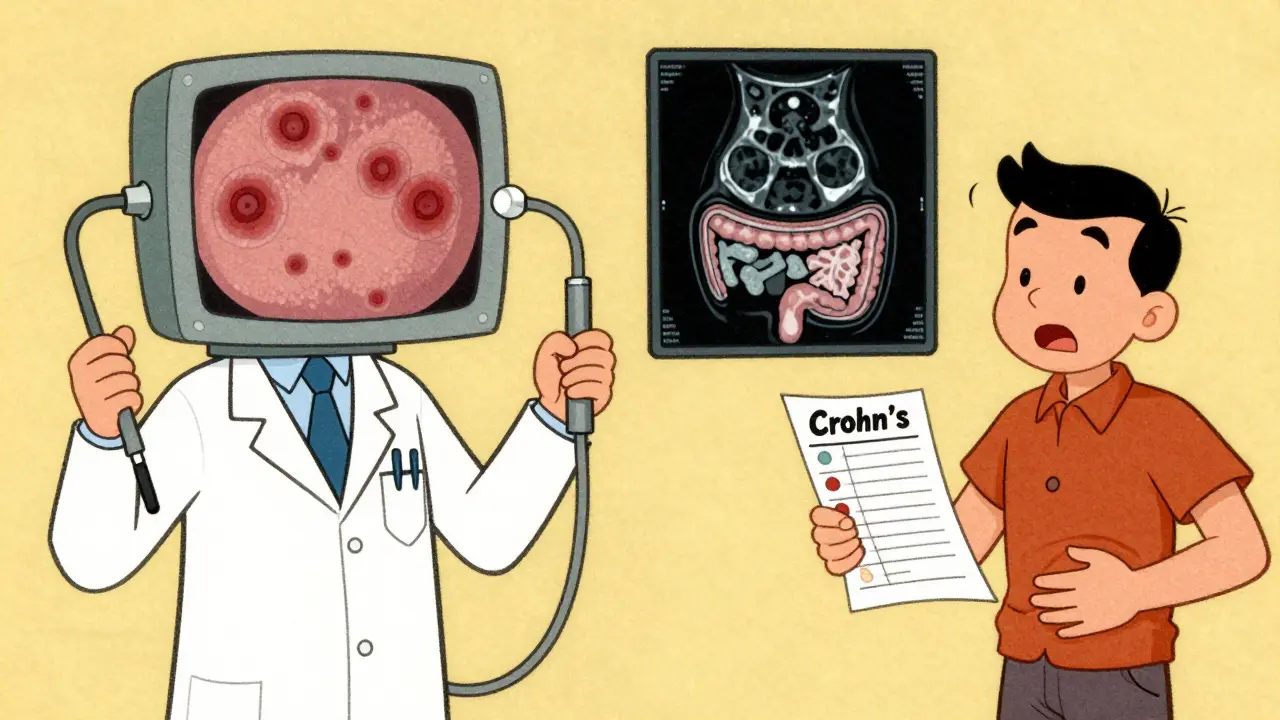

Diagnosis: What Tests Reveal

There’s no single blood test that tells you which one you have. Colonoscopy with biopsy is still the gold standard.

- In UC, biopsies show inflammation limited to the top layers. You’ll see crypt abscesses and pseudopolyps - little bumps of healing tissue.

- In Crohn’s, biopsies reveal granulomas (clumps of immune cells) in about half the cases. That’s a strong clue, though not everyone has them.

Imaging helps too. If your colon looks normal but you still have pain, diarrhea, or weight loss, a capsule endoscopy or MRI enterography might show inflammation in the small intestine - a sign of Crohn’s. UC won’t show up there.

Blood and stool markers add more clues. Fecal calprotectin is high in both, but pANCA (a type of antibody) is positive in 60-70% of UC patients and only 10-15% of Crohn’s patients. That’s a big divider.

Treatment: Why One Size Doesn’t Fit Both

Both use anti-inflammatories, immunosuppressants, and biologics. But the approach is different.

- For mild-to-moderate UC, topical treatments work wonders. Suppositories and enemas deliver 5-ASA drugs (like mesalamine) right to the inflamed rectum and colon. Up to 80% of patients respond.

- Crohn’s can’t be treated locally. You need drugs that work systemically - pills or infusions that travel through the whole body. Azathioprine, methotrexate, and biologics like infliximab or adalimumab are standard. The SONIC trial showed about 45% of Crohn’s patients go into remission with these within 17 weeks.

Biologics help both, but not equally. In the GEMINI trials, anti-TNF drugs like infliximab got 30-40% of Crohn’s patients into remission at 54 weeks. For UC? Only 20-30%. That gap matters.

Here’s the biggest difference: surgery.

- For UC, removing the entire colon and rectum (proctocolectomy) is a cure. Many patients get an internal pouch created from the small intestine - so they still go to the bathroom normally. About 10-15% of UC patients end up with this surgery within 10 years.

- Crohn’s surgery? It’s not a cure. You remove the damaged section, but the disease always comes back - often right next to the new connection. Half of Crohn’s patients need another surgery within a decade.

What Patients Really Experience

Surveys from patient communities show real-world patterns.

- UC patients talk about urgency - the sudden, uncontrollable need to go. About 87% say it’s a daily struggle. Rectal bleeding? 75% report it. It’s hard to ignore.

- Crohn’s patients talk about malnutrition. Because the small intestine absorbs nutrients, damage there leads to vitamin deficiencies, weight loss, and fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest. 65% say nutrition is their biggest challenge.

Triggers differ too. On Reddit’s r/IBD, UC patients most often blame stress. Crohn’s patients point to food - dairy, high-fiber veggies, or greasy meals. It’s not just coincidence. The location of inflammation shapes what bothers you.

The Gray Zone: Indeterminate Colitis

Not every case is clear-cut. About 10-15% of patients get diagnosed with "indeterminate colitis" - meaning doctors can’t tell if it’s Crohn’s or UC at first. This happens when the signs are mixed. A 2022 study from Switzerland found that over 12% of people initially labeled as UC were later reclassified as Crohn’s after five years, once fistulas or skip lesions appeared.

That’s why follow-up matters. What looks like UC today might be Crohn’s tomorrow. Doctors monitor for new symptoms, imaging changes, or complications over time.

The Future: What’s Coming Next

Research is moving fast. Fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) - basically, poop transplants - showed 32% remission rates in UC in the VERSUTIL trial. For Crohn’s? Only 22%. That suggests the gut microbiome responds differently to treatment based on disease type.

New drugs are on the horizon. Etrolizumab, targeting gut-specific immune pathways, is in late-stage trials for UC. Mirikizumab, which blocks a key inflammatory signal, is being reviewed for Crohn’s and could get FDA approval by late 2024.

Costs reflect the complexity. The average annual medical cost for severe Crohn’s is nearly $40,000 - higher than severe UC at $38,000. That’s because Crohn’s often needs more scans, surgeries, and biologics over time.

Bottom Line: Two Diseases, One Name

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis both fall under IBD. But they’re not the same. One is a continuous, surface-level attack on the colon. The other is a patchy, full-thickness rebellion that can strike anywhere. One can be cured with surgery. The other can’t. One responds well to enemas. The other needs whole-body drugs.

Knowing the difference isn’t just academic. It changes your treatment plan, your surgery options, your long-term risks, and even how you manage food and stress every day. If you or someone you know has IBD, ask: Is it Crohn’s? Or UC? The answer shapes the next decade of your life.

Can you have both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis at the same time?

No, you cannot have both diseases simultaneously. They are distinct conditions with different patterns of inflammation. However, about 10-15% of people are initially diagnosed with "indeterminate colitis" because their symptoms or test results don’t clearly point to one or the other. Over time, as the disease progresses, doctors usually reclassify it as either Crohn’s or UC based on new findings like fistulas, skip lesions, or small bowel involvement.

Does stress cause Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis?

Stress doesn’t cause either disease. Both are autoimmune conditions triggered by a mix of genetics, immune dysfunction, and environmental factors like diet or antibiotics. But stress can make symptoms worse. In ulcerative colitis, stress is the most commonly reported flare trigger. In Crohn’s, food and infections are more often cited. Managing stress won’t cure either condition, but it can help reduce flare frequency and severity.

Is ulcerative colitis more dangerous than Crohn’s disease?

Neither is "more dangerous" - they’re dangerous in different ways. Ulcerative colitis carries a small risk of toxic megacolon and colon cancer after 8-10 years of disease. Crohn’s has higher risks of fistulas, strictures, and repeated surgeries. Both can lead to hospitalization, disability, or needing biologics. The long-term outlook depends more on how well the disease is controlled than which type you have.

Can diet cure Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis?

No diet can cure either disease. But diet can help manage symptoms. Crohn’s patients often need low-fiber, low-residue diets to reduce blockages. UC patients may benefit from avoiding dairy or spicy foods during flares. Some people find relief with specific diets like the low-FODMAP diet, but these are tools for symptom control - not cures. Always work with a dietitian who understands IBD.

Do I need surgery if I have ulcerative colitis?

Not everyone does. Most people manage UC with medications. But if medications fail, or if you develop precancerous changes in the colon, surgery may be recommended. Removing the entire colon and rectum is the only permanent cure for UC. About 10-15% of patients have this surgery within 10 years. Many go on to live normal, active lives afterward, especially with an internal pouch.

Jonathan Noe

Man, this post broke it down better than my gastroenterologist did. I’ve had Crohn’s for 12 years and no one ever explained skip lesions like that. The cobblestone visual? Chef’s kiss. I always thought it was just random ulcers, turns out my gut looks like a cracked sidewalk after a freeze-thaw cycle.

Rachidi Toupé GAGNON

UC is just the colon throwing a tantrum. Crohn’s? It’s the whole digestive system staging a coup. 😅

Jim Johnson

Hey OP, massive thanks for this. I’ve been struggling to explain the difference to my sister since she got diagnosed with UC last year. This is the clearest thing I’ve ever read. Seriously, you should turn this into a PDF and share it with every new IBD patient. You just made someone’s life easier today 🙌

andres az

They’re hiding something. Why does Big Pharma push biologics so hard for Crohn’s but barely mention FMT for UC? 32% remission? That’s not science - that’s a marketing campaign. And why no mention of the glyphosate studies? The real cause is in your food, not your genes. Wake up.

Stephon Devereux

What fascinates me isn’t just the medical distinctions - it’s how our bodies tell stories. UC is a protest in one room. Crohn’s is a revolution across the whole country. One’s localized rage. The other’s systemic uprising. We treat symptoms, but maybe we should be listening to what the gut is trying to say. Not just patching it up - understanding why it’s burning.

Neha Motiwala

Did you know that the government has been secretly injecting aluminum into the water supply to make IBD worse? It’s in the CDC’s leaked memos. My cousin had UC and after she stopped drinking tap water, her flares vanished. Now they’re trying to ban alkaline water. You think that’s a coincidence? I don’t. And don’t even get me started on 5-ASA drugs - they’re just sugar-coated poison.

athmaja biju

In India, we treat IBD with turmeric, ginger, and yoga. No biologics needed. Western medicine overcomplicates everything. You don’t need expensive infusions - you need discipline. My uncle had Crohn’s for 20 years. He drank warm water with lemon every morning. No surgery. No hospital. Just discipline. You people are too lazy to heal yourselves.

Robert Petersen

Just wanted to say this is one of the most thoughtful, clear breakdowns I’ve seen. I’ve been living with UC for 8 years and I finally understand why my doctor keeps pushing enemas. It’s not just ‘try this’ - it’s ‘this is the only thing that targets the actual problem.’ Huge thanks for writing this. You’re helping people feel less alone.

Craig Staszak

Reminded me of the time I had to explain to my mate why I couldn’t just ‘eat better’ and get over it. He thought I was being dramatic. Then I showed him the cobblestone images. Silence. Then he bought me a coffee. Sometimes a picture says more than a thousand words.

alex clo

Thank you for the comprehensive overview. The distinction between transmural and mucosal inflammation is critical for treatment planning. The pANCA serological marker’s utility in differentiating UC from Crohn’s remains underutilized in primary care settings. Further education on serological profiling could improve diagnostic accuracy.

Alyssa Williams

My mom had UC and she swore by the low-FODMAP diet. I tried it too - not a cure but it kept me out of the ER. I still eat garlic though. Screw it. Life’s too short to be scared of food. 🤷♀️

Joanne Tan

I’m 23 and just got diagnosed with indeterminate colitis. This post made me feel less freaked out. I thought I was broken. Turns out I’m just confusing the doctors. That’s kinda funny. And kinda comforting. Thanks.

Annie Joyce

Did you know that Crohn’s patients are 3x more likely to have vitamin B12 deficiency because of terminal ileum damage? That’s why so many of us feel exhausted even when we’re sleeping 10 hours. I started taking sublingual B12 - my brain fog lifted within 2 weeks. It’s not magic. It’s biology. And no one told me. Please, if you have Crohn’s - get your B12, iron, and D checked. Seriously. It changes everything.

Rob Turner

Love how you mentioned the Swiss study on indeterminate colitis reclassification. I’m from Edinburgh and we’ve seen the same pattern. My friend was labeled UC at 22. Five years later, fistulas showed up. They reclassified it as Crohn’s. He had to get a new treatment plan. It’s wild how the body keeps rewriting its own story. Never stop monitoring.