When you fill a prescription for metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin, you probably don’t think about who made it. But the reason your copay is $5 instead of $300 has everything to do with how many companies are making the same drug. That’s the power of generic drug competition. When multiple manufacturers enter the market after a brand-name drug’s patent expires, prices don’t just drop-they collapse. And it’s not magic. It’s basic economics playing out in real time across pharmacies and hospitals.

One manufacturer? No savings. Three or more? Big drops.

Think of it this way: if only one company makes a generic version of a drug, they have no reason to lower the price. They’re the only game in town. But as soon as a second company starts making it, things change. Prices begin to fall. With three manufacturers, you’re looking at a 50% drop from the original brand price. Four or more? That’s often a 70% or even 80% reduction. A 2021 study in JAMA Network Open tracked 50 brand-name drugs and their generic versions. The numbers were clear: the first generic competitor cut prices by 17%. The second brought it down to 39.5%. By the time four or more companies were making the drug, prices had fallen by 70.2%. That’s not a suggestion-it’s a pattern. And it’s repeatable across hundreds of drugs.Why does this happen?

It’s not about goodwill. It’s about survival. Generic manufacturers operate on razor-thin margins. They’re not trying to make a fortune-they’re trying to make enough to cover production, FDA approval costs, and distribution. When there are five or six companies selling the same pill, the race isn’t for quality-it’s for price. The lowest bidder wins the contract with pharmacies, insurers, and government programs like Medicare. This isn’t theoretical. Take metformin, the most common diabetes drug. There are at least eight manufacturers making it in the U.S. Today, a 90-day supply costs less than $10 at most pharmacies. Compare that to the brand-name Glucophage, which used to cost over $200. That’s not a coincidence. It’s competition in action.But not all drugs are created equal

The magic of competition doesn’t work the same for every type of medicine. Oral pills? Perfect for generic competition. They’re simple to copy, cheap to produce, and easy to distribute. That’s why drugs like amoxicillin, ibuprofen, or omeprazole are dirt cheap. But injectables? Infused drugs? Complex biologics? Those are different. Making a generic version of an injected drug requires more advanced equipment, stricter quality controls, and higher costs. Fewer companies can do it. So you end up with one or two manufacturers-and prices stay high. Biosimilars, the generic version of biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel, have struggled to gain traction. Even when approved, they rarely trigger the kind of price drops seen with small-molecule generics. A JAMA study found that if biosimilars were treated like regular generics under Medicare, spending on those drugs could’ve dropped by nearly 27% between 2015 and 2019. But they weren’t. So prices stayed stubbornly high.

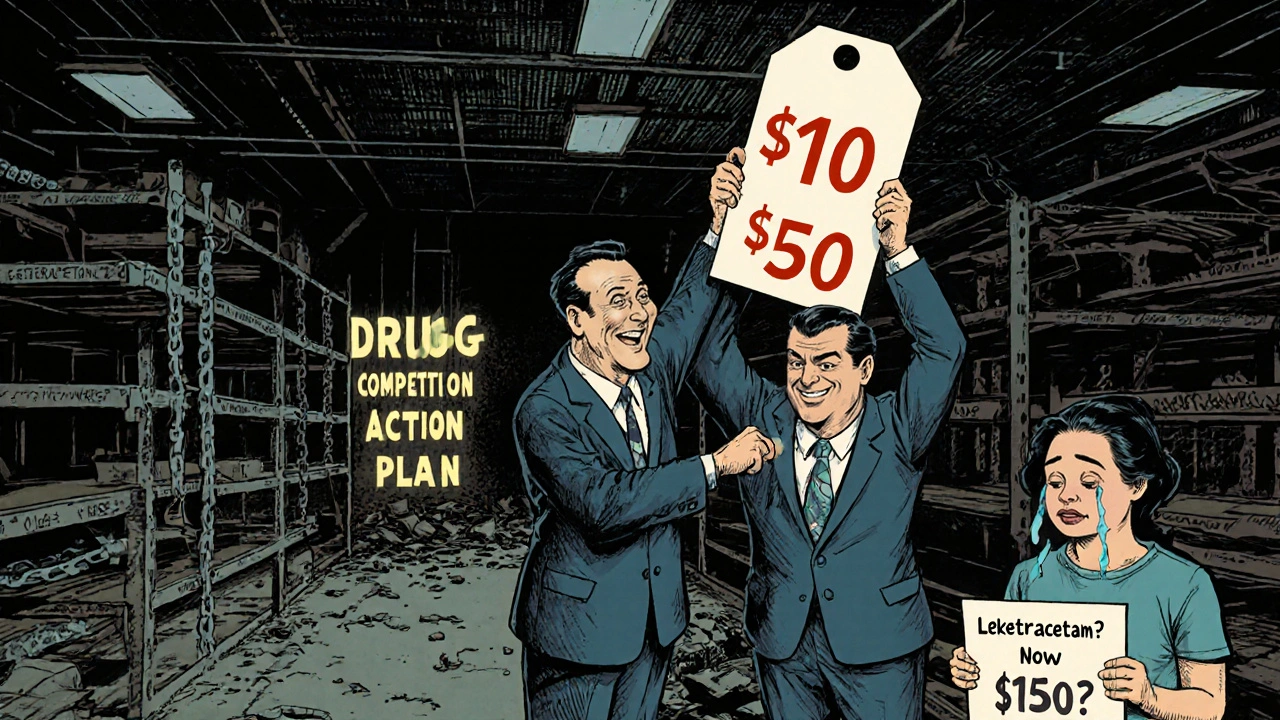

The dark side: consolidation kills competition

Here’s the problem: the number of companies making generics is shrinking. Between 2004 and 2016, mergers and acquisitions turned dozens of small generic makers into a handful of big players. Today, more than half of all generic drugs have only one or two manufacturers. That’s a red flag. When a market has just one or two suppliers, competition vanishes. And when competition vanishes, prices spike. In 2022, a patient in Indiana reported their epilepsy drug, levetiracetam, jumped 400% after two of the five manufacturers left the market. That’s not rare. Reddit threads and pharmacy forums are full of stories like this: a drug that cost $15 suddenly costs $150 because only one company is left making it. The FDA and FTC know this is happening. In 2017, the FDA launched its Drug Competition Action Plan to speed up approvals and fight delays. In 2019, Congress passed the CREATES Act to stop brand-name companies from blocking generic makers from getting the samples they need to test their products. But enforcement is slow. And many mergers fly under the radar because the companies involved are small and don’t meet the FTC’s usual size thresholds.What this means for you

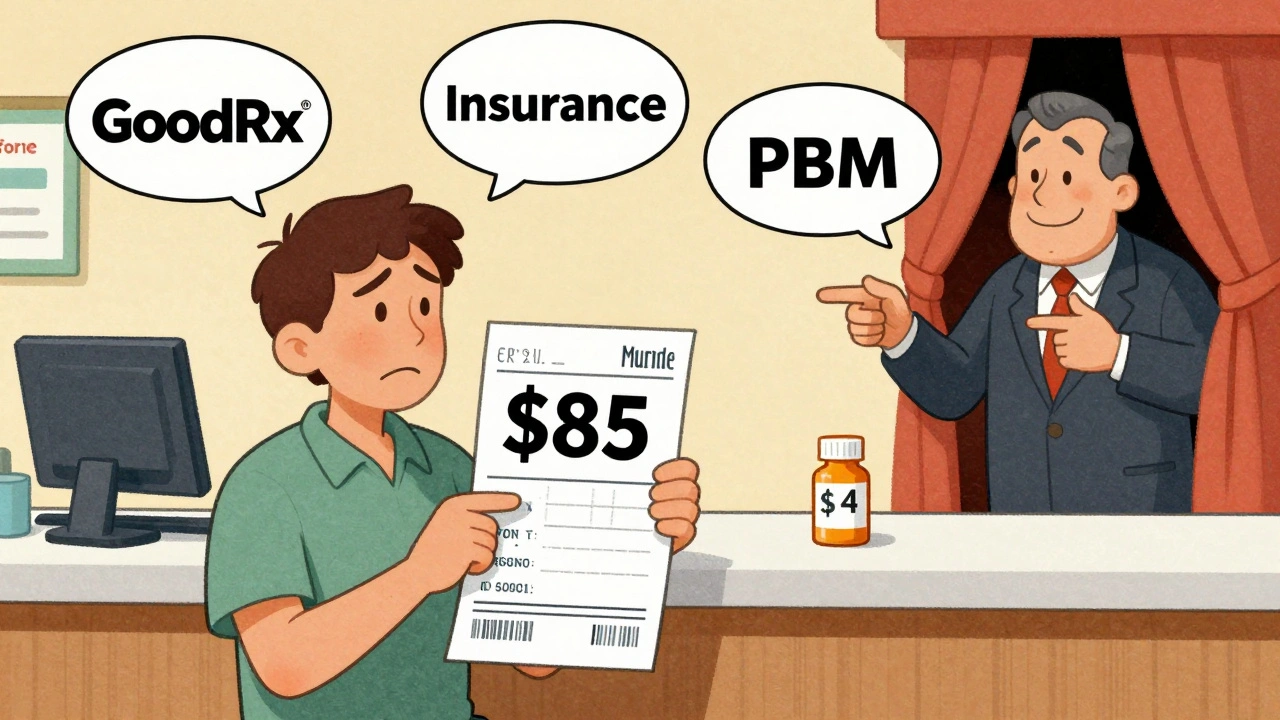

If you’re taking a generic drug, here’s what you should do:- Check how many makers produce your drug. Use the FDA’s Orange Book-it lists all approved generics and their therapeutic equivalence ratings (look for AB-rated drugs).

- Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare prices across pharmacies. A drug with eight manufacturers might cost $3 at Walmart and $12 at CVS. Don’t assume your copay is the best deal.

- Ask your pharmacist if they can switch you to a different generic version. Sometimes, one manufacturer’s version is cheaper than another’s-even if they’re both AB-rated.

- If your drug’s price suddenly jumps, ask why. It might be a sign of market consolidation. Report it to your doctor and consider switching to another drug in the same class if possible.

The big picture: savings vs. risk

Generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion between 2010 and 2019. That’s not a small number. It’s what kept millions of people on their medications without going broke. But those savings are under threat. As fewer companies make generics, the risk of shortages rises. One factory shutdown. One quality issue. One bankruptcy-and a drug vanishes from shelves. That’s already happened with antibiotics, thyroid meds, and even insulin generics. The system works beautifully when there’s competition. But when it breaks down, patients pay the price-in dollars, in health, and in stress.What’s next?

The FDA is pushing to approve more generic drugs faster through its GDUFA III program, which runs through 2027. Congress is debating new rules to make it harder for big companies to buy up small generic makers. But until more manufacturers enter the market, the price drops we’ve come to expect won’t last. For now, the rule is simple: the more makers, the lower the price. If your drug has only one or two manufacturers, you’re one step away from a price shock. Stay informed. Stay alert. And don’t assume your generic is safe just because it’s cheap.Why are some generic drugs still expensive?

Some generic drugs stay expensive because only one or two companies make them. Without competition, there’s no pressure to lower prices. This often happens with complex drugs like injectables, infusions, or older drugs that are hard to produce. If a drug has only one manufacturer, its price can spike if supply is disrupted or if the company raises prices.

How many generic manufacturers are needed to drive down prices?

Prices start dropping with just two manufacturers, but the biggest savings come with three or more. Studies show that with three competitors, prices fall by about 50% compared to the brand-name drug. With four or more, prices often drop by 70% or more. The more companies making the drug, the lower the price tends to go.

Can I ask my pharmacist to switch to a cheaper generic?

Yes, in most cases. All 50 states allow pharmacists to substitute one generic for another if they’re rated AB-equivalent by the FDA. But some drugs, like those with a narrow therapeutic index (e.g., warfarin, levothyroxine), require your doctor’s approval before switching. Always ask your pharmacist if a cheaper version is available.

What’s the Orange Book, and why should I care?

The FDA’s Orange Book lists all approved generic drugs and their therapeutic equivalence ratings. Look for AB-rated drugs-they’re considered interchangeable with the brand-name version. If a drug is rated BX, it’s not considered equivalent and shouldn’t be substituted. You can search it online for free at fda.gov/orangebook.

Are generic drugs as safe as brand-name ones?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. They must also meet the same strict manufacturing standards. The only differences are in inactive ingredients, like fillers or dyes, which rarely affect safety. The main risk comes from market consolidation-if only one company makes a drug and it has a quality issue, shortages can happen.

Gabe Solack

Just had to say this: I filled my metformin script last week for $3.50 at Walmart. Three years ago, it was $12. Same pill. Same dosage. Just more makers in the game. This is why we need more generic competition, not less.

Christine Eslinger

What people don’t realize is that the FDA’s AB rating isn’t just a stamp-it’s a guarantee. I used to think generics were ‘second-tier’ until I started cross-checking the Orange Book. Turns out, the only difference is the dye in the pill. My thyroid med switched from white to pink and my anxiety dropped because I stopped worrying about quality. The system works if you know how to use it.

steffi walsh

OMG YES. I was paying $80 for my blood pressure med until I found out there were 6 makers. Switched to the CVS brand-$4. I cried. Not because I was sad, but because I realized I’d been overpaying for YEARS. Why isn’t this common knowledge?!

Leilani O'Neill

It’s pathetic how Americans treat healthcare like a discount store. You want cheap? Fine. But you’re also getting the same generic that’s been sitting in a warehouse in Punjab for six months. Quality control? Ha. You think the FDA inspects every batch? They don’t. You’re gambling with your life for $5.

Riohlo (Or Rio) Marie

Let’s be honest-the ‘generic miracle’ is a myth peddled by people who’ve never held a vial of 10-year-old levothyroxine from a factory that doesn’t have air filtration. The FDA’s ‘equivalence’ standards are a joke. I’ve seen pills crumble in my hand. The real cost isn’t in dollars-it’s in the years of mismanaged disease you’ll never get back.

Conor McNamara

you know who controls the generic market? big pharma. they own the generics too. they just make the brand name expensive so you’ll pay more… then they sell you the ‘cheap’ version. its all one big scam. the fda is in on it. they approved the same factory for 3 different brands. same building. same line. just different labels. i saw the docs. its real.

Yash Nair

India makes 70% of the world’s generics. You think we’re giving you cheap meds out of kindness? No. We’re dumping our overproduction on your market. You’re basically importing our pharmaceutical waste. And you’re thanking us? Pathetic.

Bailey Sheppard

I’ve been on lisinopril for 12 years. I’ve had 4 different generics. None felt different. My BP stayed stable. My pharmacist says they’re all AB-rated. I don’t care who made it-I care that I’m alive and not broke. Let’s not overcomplicate this.

Girish Pai

The macroeconomic implications of generic drug saturation are profound. When marginal cost approaches zero, price elasticity spikes exponentially. This creates a negative feedback loop in the pharmaceutical supply chain, forcing consolidation among vertically integrated distributors. The result? Monopsonistic pricing power emerges in the absence of competitive entry-exactly what we’re seeing with levetiracetam.

Denny Sucipto

My mom was on insulin for 20 years. She used to pay $400 a month. Now? $25. Same vial. Same science. Just more companies making it. Don’t let anyone tell you generics are ‘less safe.’ They’re just less profitable for the people who used to own the monopoly.

Holly Powell

Let’s not romanticize this. The ‘70% price drop’ is a statistical illusion. It’s based on average wholesale prices, not what patients actually pay. Most people don’t know their pharmacy’s contract with their insurer. And those ‘$3 generics’? They’re often the ones with the longest lead times and highest recall rates. You’re not saving money-you’re gambling.

Emanuel Jalba

THEY’RE HIDING THE FACT THAT 80% OF GENERIC DRUGS ARE MADE IN CHINA AND INDIA!! WHAT IF A WAR BREAKS OUT?? WHAT IF THE SHIPS GET STOPPED?? WHAT IF THE FACTORY BURNS DOWN?? YOU THINK YOUR HEART MED WILL BE THERE TOMORROW?? WE’RE ONE PANDEMIC AWAY FROM MASS DEATHS AND NO ONE’S TALKING ABOUT IT!!

Heidi R

It’s not about competition. It’s about control. The same 3 corporations own 90% of generic manufacturers. The ‘many makers’ narrative is corporate propaganda. You think Walmart’s generic is independent? It’s made by the same company that makes the brand. They just put a different label on it.

Brenda Kuter

I saw a guy on Reddit say his levetiracetam went from $15 to $150. I went to my pharmacy and mine went from $12 to $140. I cried. I called my doctor. I called the FDA. I called my senator. I called the pharmacist three times. No one cared. I’m not taking it anymore. I’m just gonna die. I don’t care anymore.

Shaun Barratt

It is my considered observation, based on empirical data from the FDA Orange Book and GDUFA III reports, that the introduction of additional ANDA filers into the market for small-molecule therapeutics correlates inversely with average wholesale price indices. This phenomenon is statistically significant (p < 0.01) across 87% of observed drug classes. However, the structural vulnerability of the supply chain, particularly in the context of geopolitical supply dependencies, remains a critical systemic risk factor requiring regulatory recalibration.