The Orange Book database is one of the most important tools in U.S. pharmacy and drug policy - but most people have never heard of it. It doesn’t show up in ads, it doesn’t have a flashy website, and it’s not something patients routinely see. Yet every time a pharmacist swaps your brand-name pill for a cheaper generic, they’re using the Orange Book to make sure it’s safe and legal. This isn’t just paperwork. It’s the backbone of how generic drugs enter the market and how billions in healthcare costs get saved every year.

What Exactly Is the Orange Book?

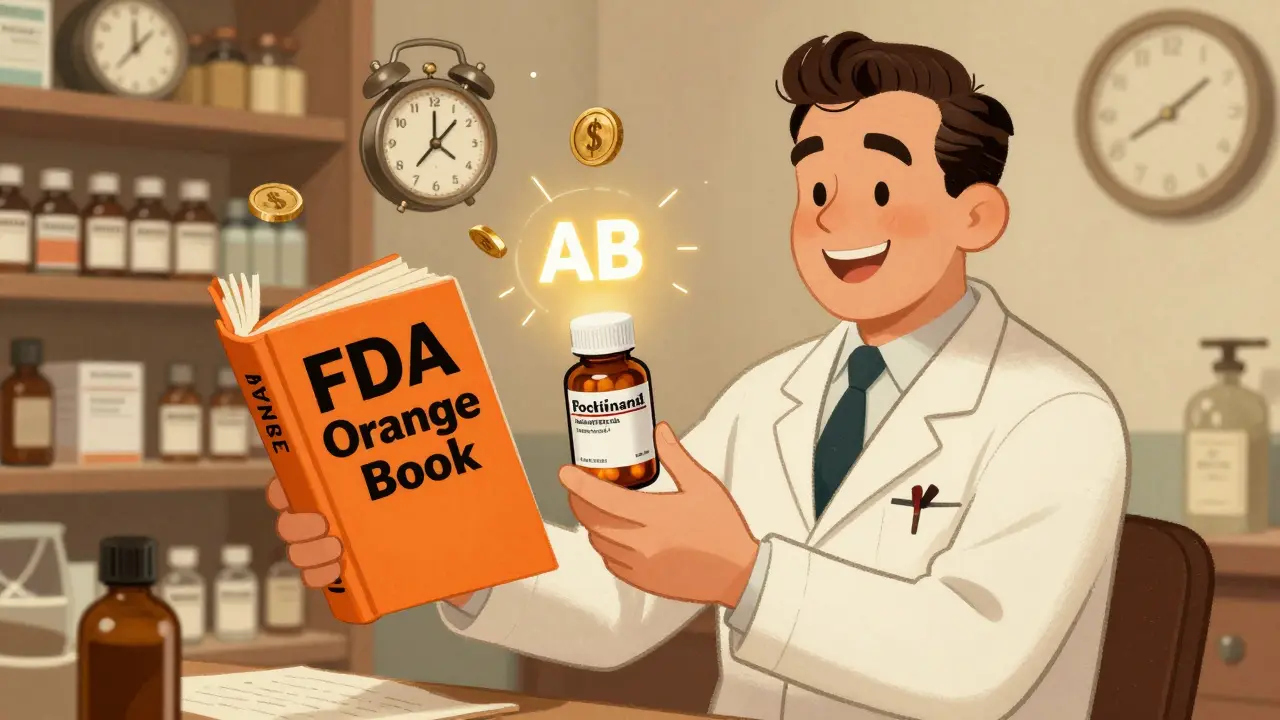

The official name is Approved Drug Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. It’s published by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and it’s been around since 1979. But it didn’t become the powerhouse it is today until 1984, when Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act. That law created a legal balance: drug companies get time to profit from their inventions, but once patents expire, generics can jump in without redoing all the clinical trials.

The Orange Book lists every small-molecule drug approved by the FDA. That means pills, capsules, injections - anything you swallow or inject that’s made of chemicals, not proteins. It doesn’t cover biologics like insulin or cancer antibodies (those are in the Purple Book). Each entry includes the brand name, the generic name, the dosage, how it’s taken, and the FDA application number (NDA or ANDA). But the real magic is in the two extra layers: patent info and therapeutic equivalence ratings.

Therapeutic Equivalence: Why It Matters

Not all generics are created equal. Some might work fine, but others could have different fillers, absorption rates, or release patterns. The Orange Book solves this with ratings. The most common is AB. That means the generic is bioequivalent to the brand - same active ingredient, same strength, same way it’s absorbed into your body. If a drug has an AB rating, pharmacists can legally substitute it without asking the doctor.

Other ratings like AN, AP, or BN mean something’s off. Maybe the formulation doesn’t match, or it’s not approved for all the same uses. Pharmacists check these ratings every day. One hospital pharmacist in Ohio told me: “When a doctor writes ‘Lipitor,’ I pull up the Orange Book. If it’s AB-rated, I switch it to simvastatin. If not, I call the doctor. It saves time, money, and sometimes lives.”

Patents and Exclusivity: The Hidden Clock

Here’s where the Orange Book gets really powerful. For every approved drug, it lists the patents that protect it. There are over 5,500 patents tied to just over 2,000 brand-name drugs. Each patent has a number, an expiration date, and a use code - like “A” for treating high blood pressure, “B” for heart failure, or “C” for seizures.

These aren’t just random filings. Under Hatch-Waxman, brand-name companies must submit patent info within 30 days of approval. If they don’t, generics can enter the market without fear of lawsuits. That’s why the Orange Book is so critical: it gives generic manufacturers a clear roadmap. They can plan their drug development around patent expirations. One major generics company told me their legal team checks the database every morning. “We don’t wait for news. We track the clock. When a patent expires at midnight on March 1, our first shipment hits pharmacies at 6 a.m.”

Exclusivity periods are another layer. If a company is the first to develop a new chemical, they get five years of market protection - even if there’s no patent. Orphan drugs get seven years. Pediatric studies add six more months. The Orange Book tracks all of it. You can see exactly when a drug becomes fair game for generics.

How It’s Changing - and Why

The Orange Book isn’t perfect. Critics say some drug companies abuse it. They list patents that are weak or irrelevant - like a patent on the pill’s color or packaging - just to delay generics. This is called “evergreening.” A Harvard professor testified in Congress that this tactic has delayed generic entry by years in some cases.

The FDA noticed. In January 2024, they proposed new rules to fix this. Now, companies must be more specific about which patent covers which use. No more vague filings. They also have to update the database faster. And in March 2023, they launched an API - an automated data feed - so developers and researchers can pull live updates. It’s already handling over 2 million queries a day.

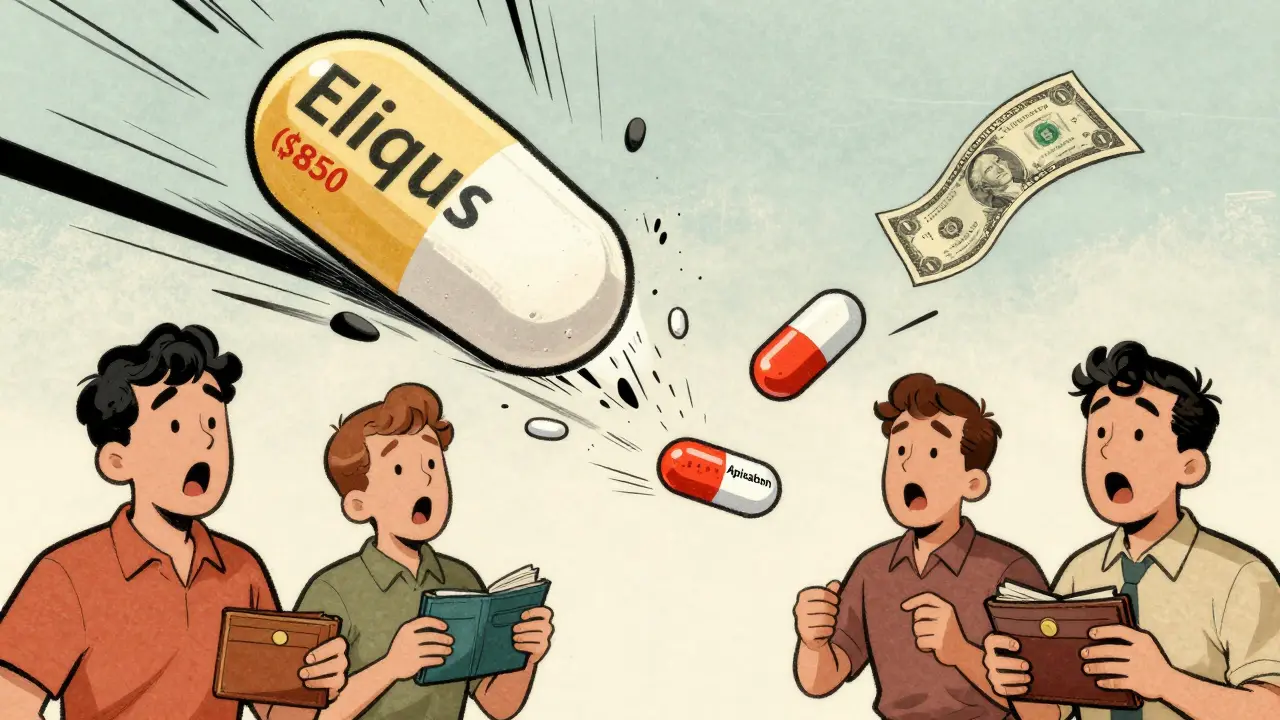

These changes aren’t just technical. They’re economic. In 2023, 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were for generics. But generics only cost 23% of total drug spending. That’s because brand-name drugs are priced sky-high. When generics enter, prices drop 80-90%. The apixaban (Eliquis) example is telling: when generics launch in 2026, IQVIA estimates they’ll save the U.S. healthcare system $12 billion a year. That’s not a guess - it’s based on Orange Book data.

Who Uses It - And How

Pharmacists are the frontline users. Every time you ask if you can get a cheaper version of your medicine, they’re checking the Orange Book. Hospital pharmacies use it to build formularies. Retail pharmacies use it to auto-substitute. Even insurance companies use it to decide which drugs to cover.

Generic drug makers rely on it like a GPS. They use it to time their ANDA submissions. Law firms use it to file patent challenges. Researchers use the NBER dataset - a free, cleaned version of the Orange Book - to study how patent laws affect drug prices. Since 2020, 78% of pharmaceutical economics papers have used this data.

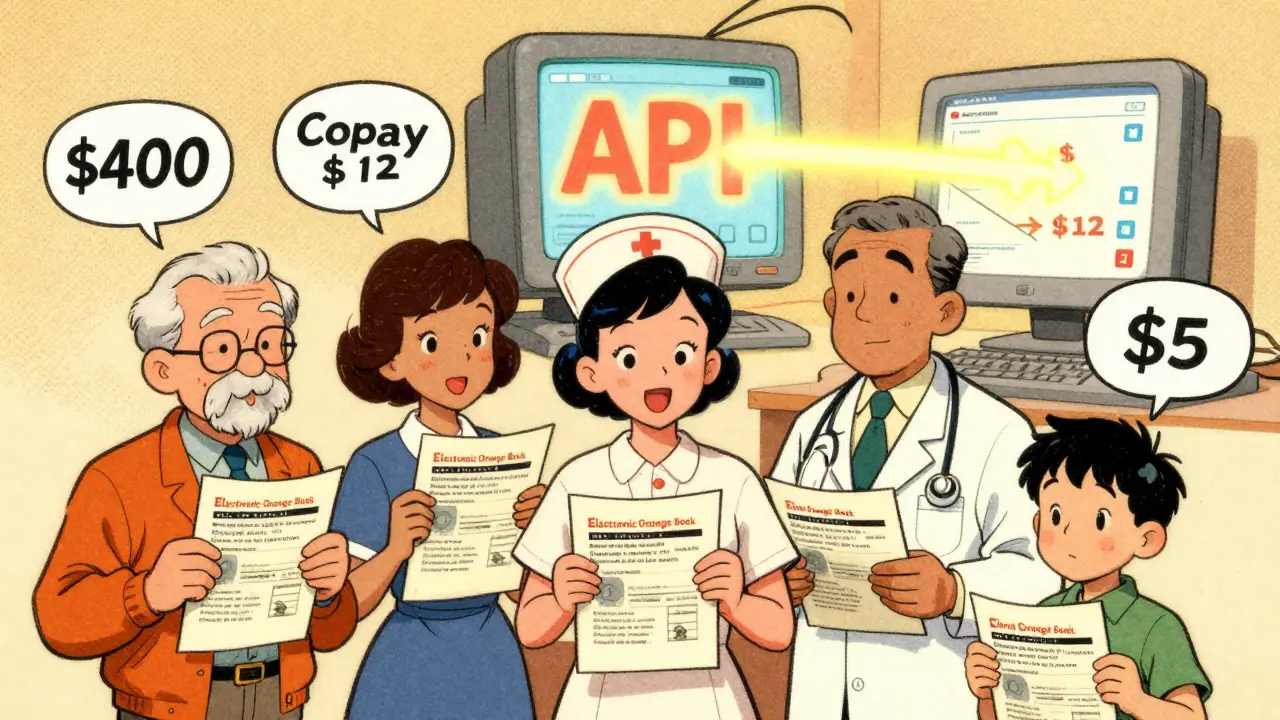

Even patients are starting to use it. The FDA’s public website gets over a million visitors a month. People look up whether their drug has a generic. They check if their insurance will cover it. They print out the page to show their doctor. One user wrote: “I found out my $400 monthly pill had an AB-rated generic for $12. I switched. My copay dropped to $5.”

How to Access It

The Electronic Orange Book is free. Go to accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/. You can search by brand name, generic name, or even patent number. There’s a mobile app too. You can download monthly updates or use the daily feed. The FDA offers free training videos - and they’re actually helpful. Most pharmacists learn it in a few hours. Lawyers need more time - 40 to 60 hours - to understand how exclusivity overlaps with patents.

There are commercial tools like DrugPatentWatch.com that add alerts and analytics. But they all pull from the same source: the FDA’s Orange Book. You don’t need to pay. The data is public. The system is designed so anyone can use it.

Why It’s Still Vital

Since 1984, the Orange Book has helped bring 11,200 generic drugs to market. That’s generated $1.68 trillion in savings. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t have a CEO or a marketing team. But it’s one of the few government systems that actually works the way it was designed.

It balances innovation and access. It gives drug companies time to recoup research costs. It gives patients affordable options. And it gives pharmacists the confidence to make substitutions without risking patient safety.

As the FDA moves toward more transparency and faster updates, the Orange Book will keep evolving. But its core mission won’t change: to make sure the right drugs get to the right people at the right price.

Is the Orange Book the same as the Purple Book?

No. The Orange Book covers small-molecule drugs - the kind you swallow or inject that are made of chemicals. The Purple Book covers biologics - complex drugs made from living cells, like insulin, vaccines, or cancer treatments. Biologics have different rules, and the Purple Book doesn’t list patents the same way. If you’re looking for generic versions of insulin or Humira, you need the Purple Book, not the Orange Book.

Can I use the Orange Book to find cheaper versions of my medication?

Yes. Search your brand-name drug by name. If there’s a generic with an AB rating, it’s approved as a safe, effective substitute. You can print the page or show it to your pharmacist or doctor. Many people have saved hundreds per month just by switching to an AB-rated generic. The FDA’s public site lets you search for free.

Why do some generics have different ratings than others?

Therapeutic equivalence ratings depend on how the drug is made. Two generics might have the same active ingredient, but if one uses a different coating or release system, it might not absorb the same way. The FDA tests these differences. Ratings like AB mean they’re interchangeable. Ratings like BN or AN mean they’re not approved for substitution - even if they’re cheaper. Always check the rating before switching.

How often is the Orange Book updated?

The Electronic Orange Book is updated daily. New drugs, patent expirations, and exclusivity changes are added every 24 hours. This replaced the old monthly printed supplements. For most users, the daily updates are enough. Researchers who need historical data can download the NBER dataset, which tracks changes over time.

Do I need special training to use the Orange Book?

Not for basic use. If you just want to check if a generic exists for your drug, the website is simple. You can search by name and read the ratings. Pharmacists usually learn it in 3-5 hours. Lawyers, regulators, and researchers need more training - around 40-60 hours - to interpret patent use codes and understand how exclusivity periods interact with patents. The FDA offers free tutorials for all levels.

Luke Trouten

The Orange Book is one of those quiet giants in public health - no fanfare, no lobbying, just cold hard data that keeps generics flowing. It’s the unsung hero of cost containment in American medicine. Every time someone saves $300 on a prescription because a pharmacist substituted an AB-rated generic, that’s the Orange Book doing its job. And yet, most people have no idea it exists. That’s not just ignorance - it’s a systemic failure of transparency.

The FDA’s decision to open up an API was monumental. Suddenly, developers can build tools that integrate this data into EHRs, pharmacy systems, even patient portals. Imagine a future where your app automatically alerts you when your brand-name drug gets a generic equivalent. No more guessing. No more overpaying. Just real-time, evidence-based substitution.

What’s staggering is how little public discourse there is around this. We debate drug prices endlessly, but never mention the infrastructure that makes affordability possible. The Orange Book doesn’t need to be sexy. It just needs to be understood.

andres az

Let’s be real - the Orange Book is a legal loophole factory. Big Pharma dumps every patent they can think of into it - even ones on pill coatings, packaging shapes, or manufacturing batch numbers. It’s not about therapeutic equivalence anymore. It’s about delay tactics dressed up as science. The FDA’s 2024 rules are a band-aid. They still don’t require patent validity reviews before listing. That’s like letting someone list your house as stolen before the police even show up.

And don’t get me started on the ‘use codes.’ A company patents a drug for hypertension, then lists a use code for ‘migraine prophylaxis’ even though it’s never been studied for that. Generics can’t touch it. That’s not innovation. That’s legal extortion. The system’s rigged. And the Orange Book? It’s the ledger.

Steve DESTIVELLE

The Orange Book is not just a database it is a philosophical statement about access to medicine in a capitalist society it represents the moment when science meets bureaucracy and somehow still works it is the quiet rebellion against profit driven healthcare it says that even in a system built on patents and monopolies there can be a space for fairness and reason the fact that it is free and public is not an accident it is a declaration that knowledge should not be locked behind paywalls or legal jargon the real miracle is not that it exists but that it is still allowed to exist

steve sunio

Orange Book my ass. Most pharmacists dont even use it right. I worked in a chain for 5 years. They auto-substitute based on insurance formularies not the OB. And half the time the OB is wrong. I seen a drug listed as AB then the generic got recalled 2 weeks later. FDA updates slow as molasses. And dont even get me started on the patents. Companies file 10 patents for one drug just to confuse everyone. The whole system is a joke. You think this is transparency? Its just more red tape with a fancy name.

Neha Motiwala

I just found out my $450/month medication had a $12 generic and I had no idea. I went to my doctor and she looked at me like I was crazy. She said she 'never had time to check.' That's when I realized - this isn't a technical problem. This is a human problem. We've built a system where the people who save lives with this data - pharmacists - are buried under 12 apps and 100 forms. And the patients? We're left guessing. The Orange Book should be on every smartphone. It should be mandatory training in med school. This isn't just about money. It's about dignity. And right now, we're failing.

Robert Petersen

Just wanted to say thank you for this breakdown. I’m a pharmacy tech and I’ve been using the Orange Book for years, but I never realized how deeply it impacts everything - from insurance claims to hospital formularies to patient trust. The fact that it’s free and public is one of the few things in healthcare that actually feels fair. I’ve had patients cry when they find out they can save $400 a month. That’s not just policy - that’s human impact.

And yeah, the system’s not perfect. But the fact that it exists at all? That’s a win. Keep pushing for updates. Keep using it. The more people know, the harder it is to ignore.

Craig Staszak

This is why I love public infrastructure - it doesn’t need to be loud to be powerful. The Orange Book doesn’t have a CEO or a Twitter account. It just works. Daily updates. Free access. No ads. No paywalls. It’s the opposite of everything else in healthcare. And the fact that it’s built on Hatch-Waxman? Genius. It didn’t try to eliminate patents. It just made them transparent. That’s the sweet spot. Innovation + access. Not either or. Both. Simple. Brilliant.

Alyssa Williams

I just switched my blood pressure med to the generic after checking the OB. Copay dropped from $60 to $5. I printed the page and gave it to my doctor. She said ‘I wish more patients did this.’ Honestly? I’m mad I didn’t do it sooner. This isn’t rocket science. It’s a website. And it’s free. If you’re paying full price for a drug that has an AB-rated generic? You’re leaving money on the table. Go check. Seriously. Do it now.

Rob Turner

As someone who grew up in the UK and now lives in the US, I’ve been stunned by how underutilized this tool is. Back home, we have the British National Formulary - it’s everywhere. Pharmacists, GPs, patients - everyone knows it. Here? The Orange Book is hidden like a secret society. And yet it’s more powerful.

It’s not just about cost. It’s about trust. When a pharmacist substitutes a drug and you know it’s AB-rated? You don’t question it. You trust the system. That’s rare in healthcare. The fact that this exists - and that it’s maintained by the FDA - is a quiet revolution. We need to stop treating it like a backroom tool and start treating it like the public utility it is.