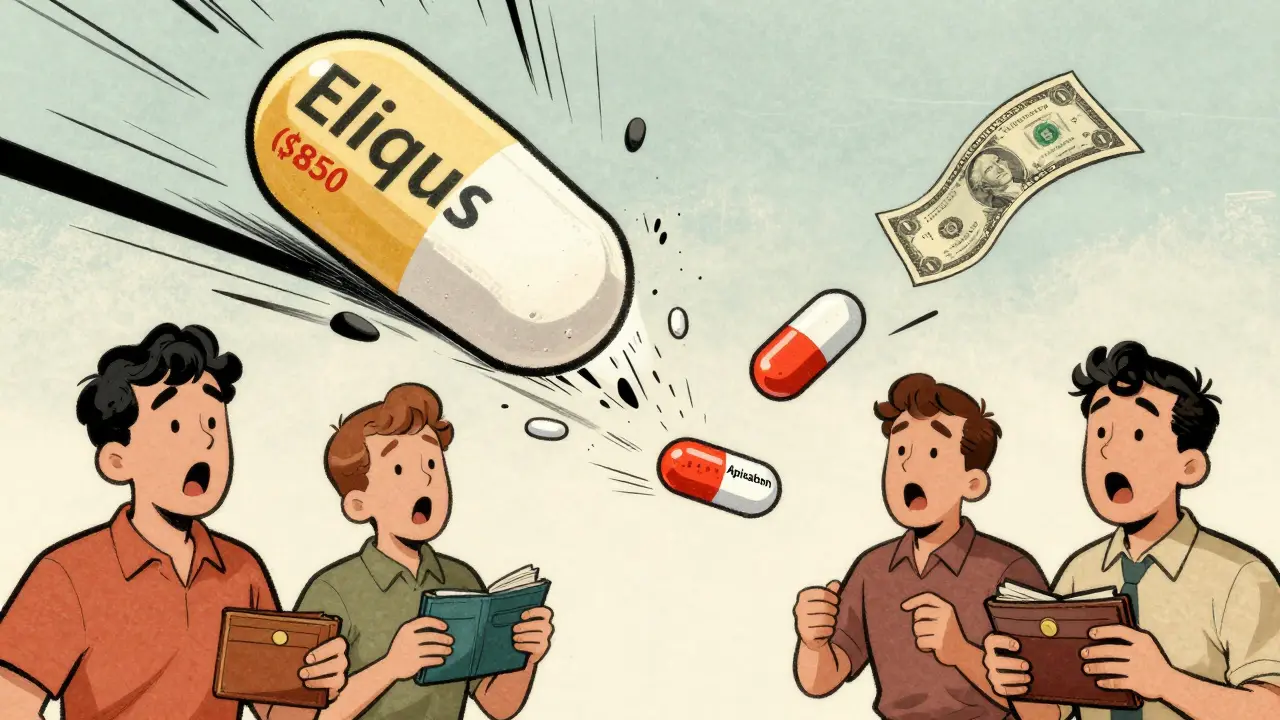

When a drug’s patent runs out, prices don’t just dip-they plummet. For patients paying hundreds a month for brand-name medications, this isn’t just a business detail-it’s a life-changing moment. Take apixaban, the blood thinner sold as Eliquis. Before its patent expired in 2020, a 30-day supply cost over $850. Within months of generic versions hitting the market, the same dose dropped to under $10. That’s not a typo. That’s the real-world impact of patent expiration.

Why Patents Exist-and Why They End

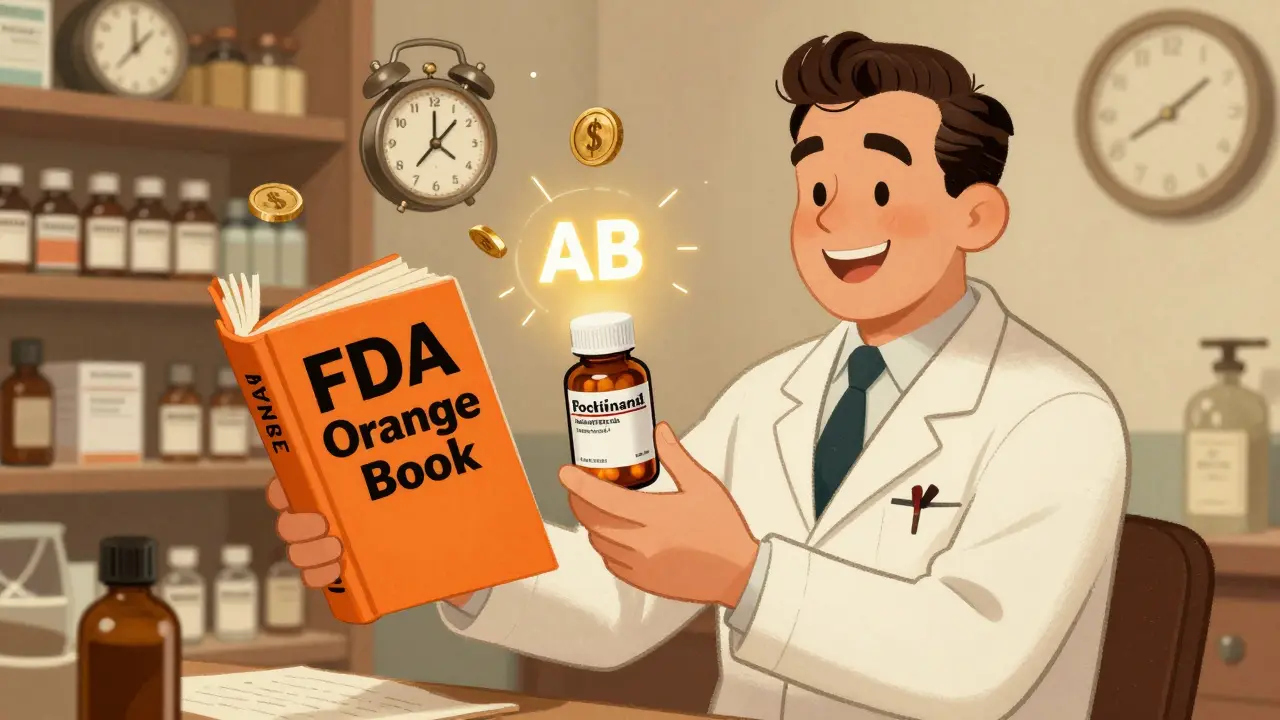

Pharmaceutical companies spend over $2 billion on average to bring a new drug to market. Patents give them 20 years of exclusive rights to sell that drug without competition. This monopoly is meant to reward innovation and fund future research. But once the patent expires, the rules change. Generic manufacturers can step in, copy the formula, and sell the same medicine at a fraction of the cost. The system was designed this way on purpose. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act in the U.S. created a legal pathway for generics to enter the market without repeating costly clinical trials. In return, brand-name companies got a small extension on their patent if they had to delay approval due to regulatory reviews. It was a trade-off: innovation protected, but competition guaranteed.How Fast Do Prices Drop After Patent Expiration?

The drop isn’t gradual-it’s explosive. The first generic competitor usually cuts the price by 15% to 20%. The second drops it another 30%. By the time five or more generics are on the shelf, the price often falls below 20% of the original. A 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum tracked 505 drugs across eight countries and found that in the U.S., prices fell 82% over eight years after patent expiry. In Germany, it was 58%. In Switzerland, only 18%. Why such a big difference? It’s not just about how many generics enter-it’s about how fast. In the U.S., the average generic arrives 30 months after patent expiration. In Europe, it’s often 12 to 18 months. That delay means patients pay higher prices longer. And it’s not just time-it’s strategy.The Patent Thicket Problem

Not all patent expirations are equal. Some drugmakers don’t just rely on one patent. They build a “patent thicket”-a web of dozens, sometimes over a hundred, secondary patents on tiny changes: a new pill coating, a slightly different dosage schedule, a packaging tweak. These don’t make the drug better-they just delay competition. Take Humira (adalimumab), the top-selling drug in history. Its original patent expired in 2016. But AbbVie filed over 130 follow-up patents. By the time the first biosimilar, Amjevita, launched in January 2023, it was seven years late. Even then, prices didn’t crash right away. Why? Rebates and contracts between drugmakers and insurers kept Humira’s list price high. Patients didn’t see the savings until their pharmacy tried to substitute the cheaper biosimilar. The same pattern happened with Ozempic and Wegovy (semaglutide). The base compound patent expires in 2026, but the manufacturer has filed 142 patents across different formulations. Experts estimate these thickets extend effective exclusivity by 12 to 14 years beyond the original patent. That’s not innovation-it’s delay.

Why Some Drugs Don’t Get Cheaper Right Away

Even when generics are approved, they don’t always reach patients quickly. Insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) control which drugs are covered and at what cost. Many keep brand-name drugs on preferred formularies because they get rebates from the manufacturer. So even if a generic is cheaper, your plan might not cover it unless you jump through hoops. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 22% of insured adults said their insurance made it harder to switch to a generic, even after patent expiration. Pharmacists in 49 U.S. states can automatically substitute generics-but only if the doctor didn’t write “dispense as written.” Many don’t know this rule. Patients assume the brand is still the best option. They’re not wrong to be confused.Biologics Are Different-and Harder to Copy

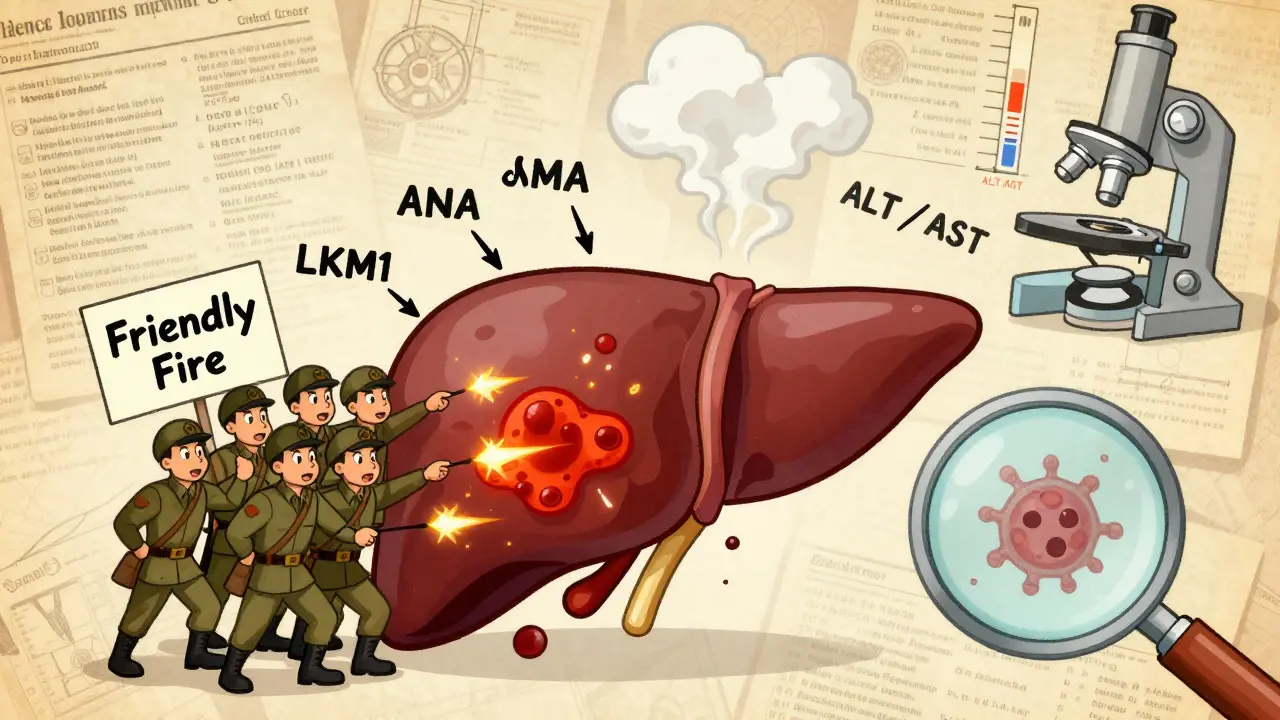

Not all drugs are pills. Biologics like Humira, Enbrel, and insulin are made from living cells. They’re complex, expensive to produce, and nearly impossible to copy exactly. So instead of generics, we get “biosimilars”-drugs that are highly similar but not identical. The approval process is longer, costlier, and more technical. That’s why biosimilars take longer to arrive and drop less in price. The FDA approved its first biosimilar in 2015. By 2023, only 45% of the market for reference biologics was made up of biosimilars. Europe is ahead-they aim for 70% by 2027. In the U.S., the average time from patent expiry to biosimilar launch is still 4 to 6 years. And the cost to develop one? $2 million to $5 million per product. That’s a high barrier for small manufacturers.Who Benefits the Most?

The biggest winners are patients and public health systems. The Congressional Budget Office estimates generic and biosimilar competition will save the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion over the next decade. Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers all see lower spending. Patients pay less out of pocket. A 2023 study showed 68% of insured adults saw lower costs when generics became available. But the savings aren’t automatic. They require competition. They require transparency. And they require regulators to stop letting companies game the system with patent thickets. The FDA approved 870 generic drugs in 2023-up 12% from the year before. That’s progress. But the I-MAK 2025 report found that 78% of new patents filed in the U.S. weren’t for new drugs-they were for old ones with minor tweaks.

What’s Changing Now?

There’s momentum to fix this. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 let Medicare negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs starting in 2026. That’s a direct challenge to the monopoly model. The U.S. Patent Office has started rejecting obvious secondary patents. The European Commission proposed caps on supplementary protection certificates. The FDA is speeding up reviews for complex generics. But the biggest shift is cultural. Patients are asking more questions. Pharmacists are pushing for substitution. Doctors are prescribing generics by default. And insurers are starting to drop rebates that keep brand drugs on top.What You Can Do

If you’re on a brand-name drug with an expired patent:- Ask your doctor if a generic or biosimilar is available.

- Call your pharmacy and ask why you’re not getting the cheaper version.

- Check your insurance formulary-sometimes switching to a generic requires a prior authorization.

- Use tools like GoodRx to compare cash prices-often the cheapest option isn’t covered by insurance at all.

What’s Next?

The next wave of patent expirations will hit hard. Between 2025 and 2030, drugs worth over $220 billion in annual sales will lose protection. That includes more biologics, more insulin products, and more heart and diabetes drugs. The savings could reshape healthcare spending. But only if we don’t let patent thickets and rebate tricks block the way. The math is simple: more competitors = lower prices. The challenge is making sure those competitors can actually enter the market. Until then, the real winners aren’t the drugmakers-they’re the patients who know how to ask for the cheaper option.Do drug prices always drop after a patent expires?

Not always, but they usually do. Prices drop sharply when multiple generic manufacturers enter the market. However, if the brand company uses patent thickets, rebate deals with insurers, or delays biosimilar entry, the price drop can be delayed or minimized. In some cases, like with Humira, prices stayed high for years after patent expiry because of complex contracts.

How long does it take for generics to appear after a patent expires?

In the U.S., generics typically arrive 18 to 30 months after patent expiry. In Europe, it’s often 12 to 18 months. Delays happen due to legal battles, complex manufacturing requirements, or patent thickets. For biologics, biosimilars can take 4 to 6 years to appear because of stricter approval rules.

Why are some generics still expensive?

Sometimes, only one or two companies make the generic, so there’s little competition. Other times, insurance plans favor the brand drug because they get rebates from the manufacturer. Also, some complex drugs (like inhalers or injectables) are harder to copy, so fewer companies can make them, keeping prices higher.

Can I ask my pharmacist to switch me to a generic?

Yes, in 49 U.S. states, pharmacists can automatically substitute a generic for a brand-name drug unless the doctor specifically wrote “dispense as written.” Always ask your pharmacist if a cheaper generic is available-even if your insurance doesn’t list it as preferred. Cash prices at pharmacies like Walmart or Costco are often lower than insurance copays.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule pills, like aspirin or metformin. Biosimilars are highly similar but not identical versions of complex biologic drugs made from living cells, like Humira or insulin. Biosimilars are harder to produce, take longer to approve, and usually cost less but not as dramatically as generics.

Will Medicare negotiate prices after patent expiration?

Yes. Starting in 2026, Medicare will negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs each year, including some that just lost patent protection. This could push manufacturers to lower prices faster to avoid negotiation. It’s a new tool to make sure patent expiration leads to real savings, not just paperwork.

Glendon Cone

This is the kind of post that makes me believe in progress. I used to pay $700 for my dad's blood thinner. Now he pays $8. No magic, just competition.

Pharmacists are heroes. Just ask them to swap it.

Hayley Ash

Oh please. The ‘generic miracle’ is a myth. Prices drop because insurers force it. Patients? Still paying more than they should. And don’t get me started on how the FDA approves generics like they’re cereal boxes.

Kelly Gerrard

The system works exactly as designed and you’re all acting like it’s broken because you didn’t get a free vacation

Patents expire so innovation can be rewarded then shared

Stop whining about capitalism working

Aayush Khandelwal

Patent thicketing is the ultimate financial engineering play-layering IP like a lasagna of legal nonsense. The real innovation isn’t in the molecule anymore, it’s in the litigation department.

Big Pharma’s R&D budget is now 80% lawyers, 20% chemists. And we call this progress?

srishti Jain

Why do we even care? They’ll just make a new drug and charge $10k anyway.

henry mateo

i didnt know pharmacists could switch stuff automaticly?? i thought u needed a new script??

im gonna ask mine tomorrow lol

Kunal Karakoti

There’s a quiet tension here between innovation and access. The patent system was meant to balance them. But when the scales are bent by corporate strategy rather than science, we’re no longer incentivizing medicine-we’re incentivizing delay.

Henry Ward

You people act like generics are some kind of moral victory. They’re not. They’re just cheaper versions of something that cost billions to create.

And now you’re mad because the people who risked everything aren’t getting paid?

Pathetic.

Joseph Corry

Ah yes, the naive belief that ‘competition’ = ‘lower prices.’ As if markets are pure and regulators are saints.

The real story? PBMs are the invisible oligarchs. They pocket rebates. They control formularies. And they don’t care if you’re bankrupt-you’re just a data point in their quarterly report.

Colin L

I’ve been in this game for 22 years. I’ve seen the same script play out. The brand drug drops 10% in the first month, then 5% every quarter, then it flatlines because the generics are all owned by the same three conglomerates.

There’s no competition. Just a redistribution of monopoly rent.

And the FDA? They’re too busy approving 870 generics a year to notice that 70% of them are made in the same two factories in India and China.

So yes, prices are lower. But safety? Quality? That’s the real question you’re all ignoring.

kelly tracy

So what? The rich still get the best care. The rest of us just get cheaper pills that might not work as well.

And don’t even get me started on how the FDA lets generics skip Phase 3 trials.

It’s not healthcare. It’s a lottery.

Cheyenne Sims

America invented the modern pharmaceutical industry. We don’t need Europe’s socialist pricing models. If you want cheap drugs, move to Canada. But don’t expect us to break the system that made cures possible.

Shae Chapman

I just switched my Ozempic to the generic and my copay went from $400 to $12 😭😭😭

My doctor didn’t even know I could do it. I had to beg my pharmacist.

Y’all need to talk to your pharmacy. It’s not hard. It’s just not obvious.

Nadia Spira

The entire system is a performance art piece funded by taxpayer money.

Patent expiration? A theatrical illusion.

The real value extraction happens in the formulary negotiations, the rebate pipelines, and the silent collusion between PBMs and manufacturers.

You think you’re saving money? You’re just being funneled through a different funnel.

Sandeep Mishra

Let me tell you something. Back in India, my uncle got his diabetes meds for $2 a month. Not because of generics. Because the government broke the patent under public health emergency.

There’s a difference between innovation and exploitation.

We don’t need more patents. We need more humanity.