Autoimmune encephalitis isn’t something you hear about every day-but when it happens, it changes everything. Unlike infections that cause brain swelling, this condition is your own immune system turning against your brain. It attacks proteins on nerve cells, triggering seizures, memory loss, hallucinations, and even coma. The good news? If caught early, most people recover. The bad news? It’s often mistaken for a psychiatric disorder or the flu. That delay can cost you months-or worse.

What Are the Red Flags That Shouldn’t Be Ignored?

Most people with autoimmune encephalitis don’t wake up one day with a diagnosis. Symptoms creep in over days or weeks. At first, it might feel like a bad case of the flu: headache, fever, nausea, or diarrhea. But then something shifts. You start forgetting names. You can’t focus at work. You feel anxious for no reason-or suddenly become aggressive, paranoid, or withdrawn. These aren’t just "stress symptoms." They’re neurological red flags. In over 85% of cases, memory problems show up early. You forget conversations, repeat questions, or get lost in familiar places. Seizures are common too-especially if they’re new, unexplained, or don’t respond to typical epilepsy meds. About 60% of people with anti-LGI1 antibodies have sudden, brief muscle jerks in the face or arm, called faciobrachial dystonic seizures. These look like twitches, but they’re a hallmark of this specific type of encephalitis. Autonomic dysfunction is another clue you’re not dealing with a typical mental health issue. Your heart races without cause. Your blood pressure drops when you stand up. You sweat excessively or stop sweating altogether. Sleep gets wrecked-insomnia one night, sleeping 14 hours the next. These aren’t side effects of anxiety. They’re signs your brainstem is under attack. If you or someone you know has had these symptoms for more than a week, especially with no clear infection, get tested. Don’t wait for a psychiatrist to call it "psychosis." Autoimmune encephalitis can mimic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or dementia. But it’s treatable-if you catch it fast.Which Antibodies Are Behind the Damage?

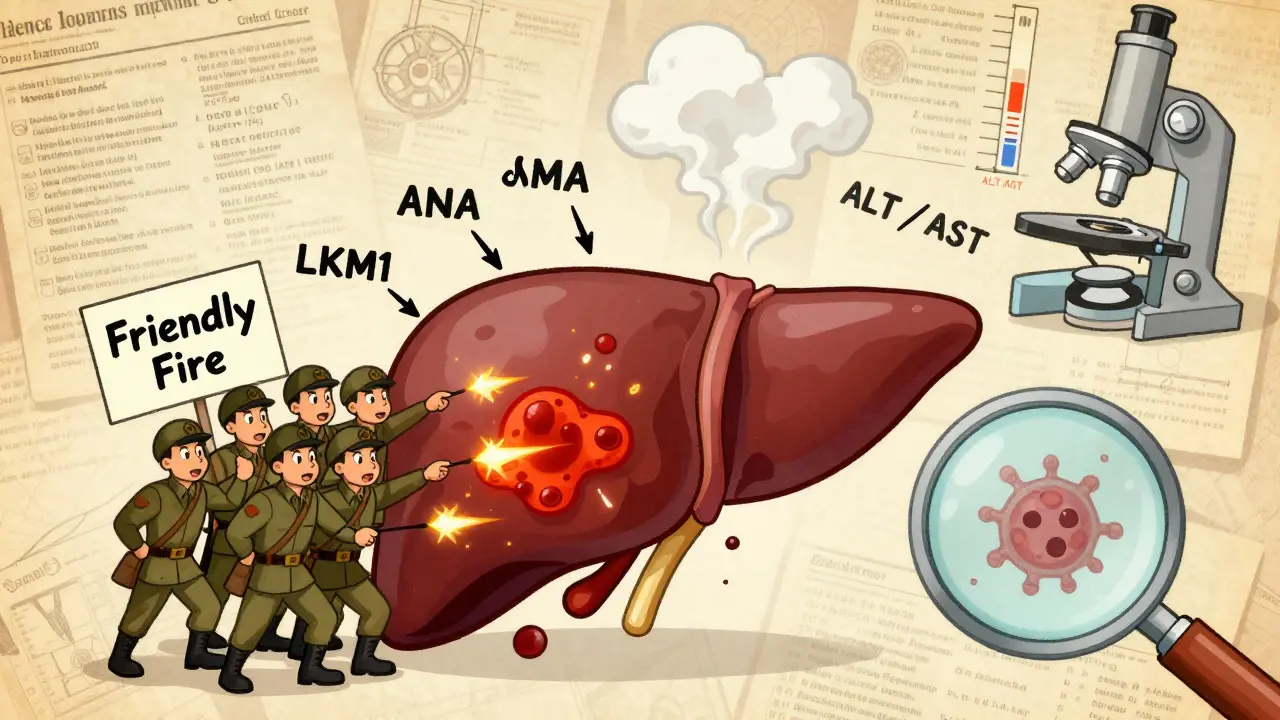

There are over 20 known antibodies linked to autoimmune encephalitis. They’re grouped by where they attack: on the surface of nerve cells or inside them. Surface antibodies are usually treatable. Intracellular ones often mean cancer is hiding somewhere. Anti-NMDAR is the most common, making up about 40% of cases. It hits young women hardest-median age 21. Half of these patients have an ovarian teratoma, a benign tumor that tricks the immune system into attacking the brain. Remove the tumor, and many patients improve dramatically. Even if no tumor is found at first, screening must be repeated every 4-6 months for two years. Some tumors show up months later. Anti-LGI1 shows up in 15% of cases, mostly in men over 60. It’s tied to low sodium levels (hyponatremia) in 65% of patients. The faciobrachial seizures are so specific, doctors can often suspect this type before antibody results come back. Recovery is good-55% fully recover by two years-but recurrence happens in 35% of cases. That’s why long-term follow-up is critical. Anti-GABABR is rare (5% of cases) but dangerous. Half the people with this antibody have small cell lung cancer. If you’re over 50 and have seizures with memory loss, this needs to be ruled out immediately. Mortality is higher here-not because of the brain inflammation, but because of the cancer. Less common but still important: anti-CASPR2 (often with neuromyotonia or Morvan’s syndrome), anti-AMPAR (linked to thymoma or lung cancer), and anti-GFAP (affects the brain’s support cells, often with spinal cord involvement). Each one has its own pattern. That’s why testing both blood and spinal fluid matters. CSF is 15-20% more sensitive for detecting anti-NMDAR antibodies, for example.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single test. Diagnosis is a puzzle made of clinical signs, lab work, and imaging. The 2016 international criteria, updated in 2023, help doctors piece it together. First, they rule out infection. Infectious encephalitis usually has a much higher white blood cell count in spinal fluid-sometimes over 1,000 cells/μL. In autoimmune cases, it’s usually under 100. Protein levels are only mildly raised. Oligoclonal bands? Usually negative. That’s a key difference. MRI scans can be normal in up to half of cases. But when there’s a change, it’s often subtle: swelling in the hippocampus (part of the limbic system), with contrast enhancement. That’s why limbic encephalitis is a common term-it points to inflammation in the memory and emotion centers of the brain. EEGs almost always show something abnormal-generalized slowing, or epileptiform activity. But they don’t show the periodic spikes you’d see in viral encephalitis like herpes. That’s a clue. Antibody testing is the gold standard. Serum (blood) is tested first, but CSF is often needed for confirmation. Labs like Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, and specialized university centers run these panels. Results can take weeks. But here’s the catch: if the clinical picture is strong, don’t wait. Start treatment while you wait.What’s the Treatment Plan?

Treatment is fast, aggressive, and tiered. The goal: shut down the immune attack before it kills brain cells. First-line therapy starts within days. High-dose IV steroids-1 gram per day for five days. Most patients (68%) show improvement in 7-10 days. Alongside that, IV immunoglobulin (IVIg) is given: 0.4 grams per kilogram of body weight daily for five days. About 60-70% respond. These treatments don’t cure the disease-they calm the immune system enough to let the brain heal. If a tumor is found-like an ovarian teratoma or lung cancer-removing it is step one. In anti-NMDAR cases, 85% of patients improve within four weeks after surgery. No tumor? Still treat the immune attack. Don’t assume no tumor means no cancer. Repeat scans and PET/CT every 4-6 months for two years. Second-line treatments kick in if there’s no improvement after two weeks. Rituximab (a B-cell depleter) is given weekly for four weeks. It works in 55% of cases. Cyclophosphamide, a stronger chemo-like drug, is used in 48% of refractory cases. Tocilizumab, an IL-6 blocker, is newer but shows 52% response in stubborn cases. Plasma exchange (plasmapheresis) is used for critically ill patients-those in ICU, with seizures or breathing problems. Five to seven sessions over two weeks clear out the bad antibodies. About 65% improve within two weeks.

Praseetha Pn

This is why I stopped trusting Western medicine. They call it 'psychosis' for years while your brain gets eaten alive. I know a woman in Bangalore who was misdiagnosed for 18 months-her family had to fly her to Germany because no one in India even knew anti-NMDAR existed. They finally found it because her cousin was a neuro grad student. Who the hell lets this happen? 🤬

Dayanara Villafuerte

I’m a nurse in Texas and I’ve seen this twice. First time, the ER doc sent the girl home with Xanax. Second time? Mom showed up with a printed copy of this exact post. We started steroids that night. She’s back at college now. 🙌❤️

Kristin Dailey

America’s healthcare system is broken. If this happened in a country with real medicine, they’d test for antibodies within hours.

Naomi Keyes

I must point out-your claim that CSF is 15-20% more sensitive for anti-NMDAR is outdated. The 2023 update from the International Consensus Group states that paired serum/CSF testing increases sensitivity by 31% when both are positive, not CSF alone. Also, oligoclonal bands are not 'usually negative'-they're positive in 38% of cases. You're oversimplifying.

kenneth pillet

i read this last night. my sister had all the symptoms but got diagnosed as anxiety. she’s better now but still has bad memory days. thanks for writing this. really helped me understand.

Ryan Otto

The real issue here is not the medical system-it’s the decline of neuroscientific literacy among clinicians. The fact that a condition with such a distinct clinical profile is routinely misattributed to psychiatric etiologies speaks volumes about the erosion of neurological training in residency programs. Furthermore, the commercialization of diagnostic testing has created a two-tiered system: those who can afford to pay for antibody panels out-of-pocket receive timely intervention, while others languish in psychiatric limbo. This is not medicine. It is systemic negligence masked as protocol.

Jay Clarke

They don’t want you to know this. Big Pharma doesn’t profit from steroids and IVIg. They profit from antidepressants and antipsychotics that keep you docile for life. This is the exact same playbook they used with Lyme disease. Wake up.

Eric Gebeke

I can't believe people are still falling for this. You're all just being manipulated by fear. Autoimmune encephalitis is extremely rare. The real problem is that people are too lazy to take responsibility for their mental health. If you're having 'memory loss' and 'hallucinations', maybe you need to stop scrolling TikTok and get some sleep. This post is just fearmongering dressed up as science.

Chuck Dickson

Hey everyone-this is such an important post. I’ve been through this with my brother. He didn’t recover fully, but rehab and melatonin changed his life. If you or someone you love is struggling, please don’t give up. There’s hope. And if you’re a doctor reading this? Please, please test for antibodies early. You could save someone’s future. 💪🧠

Jodi Harding

It’s not about antibodies. It’s about who gets listened to. A woman with memory loss is 'hysterical'. A man with the same symptoms is 'neurological'. The system is rigged.

Zoe Brooks

I’m so glad this exists. I’ve been telling my friends for years: if something feels wrong in your brain, trust it. Even if the doctors shrug. Keep pushing. I’m alive today because my mom refused to accept 'it’s just stress'. 🌱