When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same results as the brand-name version. But what if your body reacts differently-not because the medicine is weaker, but because of your genes? This isn’t rare. It’s happening more often than you think. And your family history might hold the key.

Why Your Body Responds Differently to the Same Drug

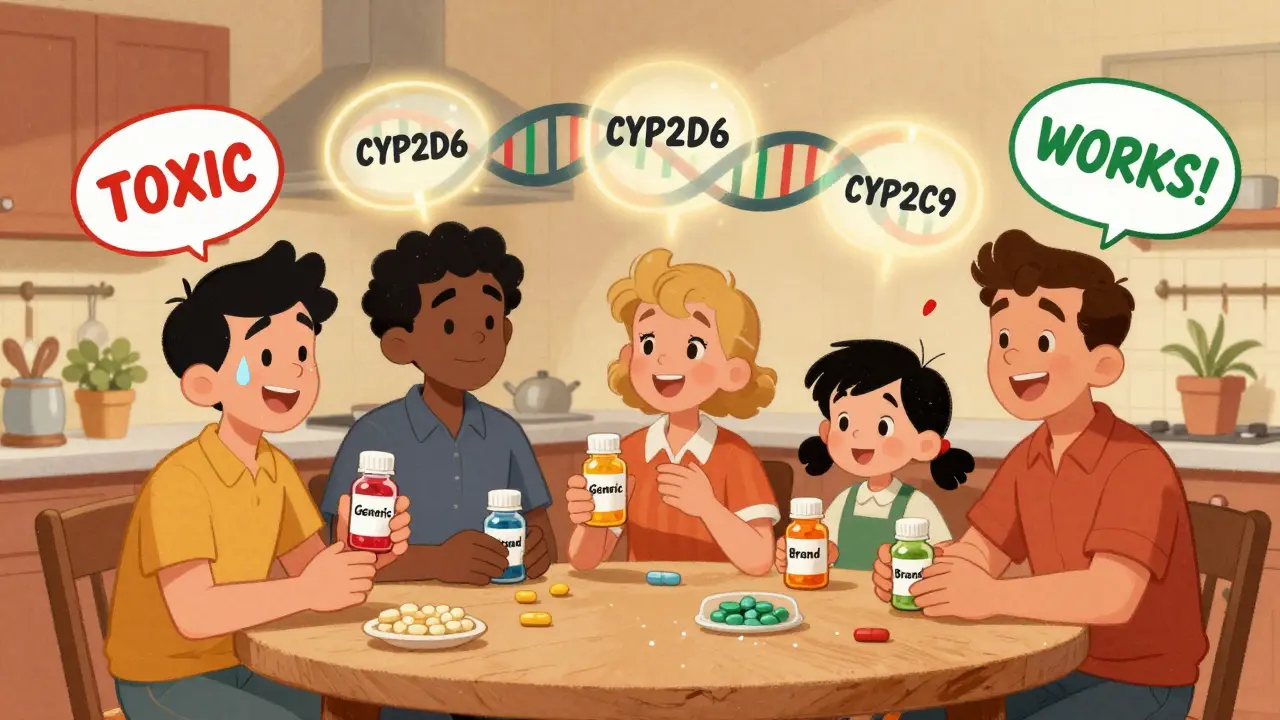

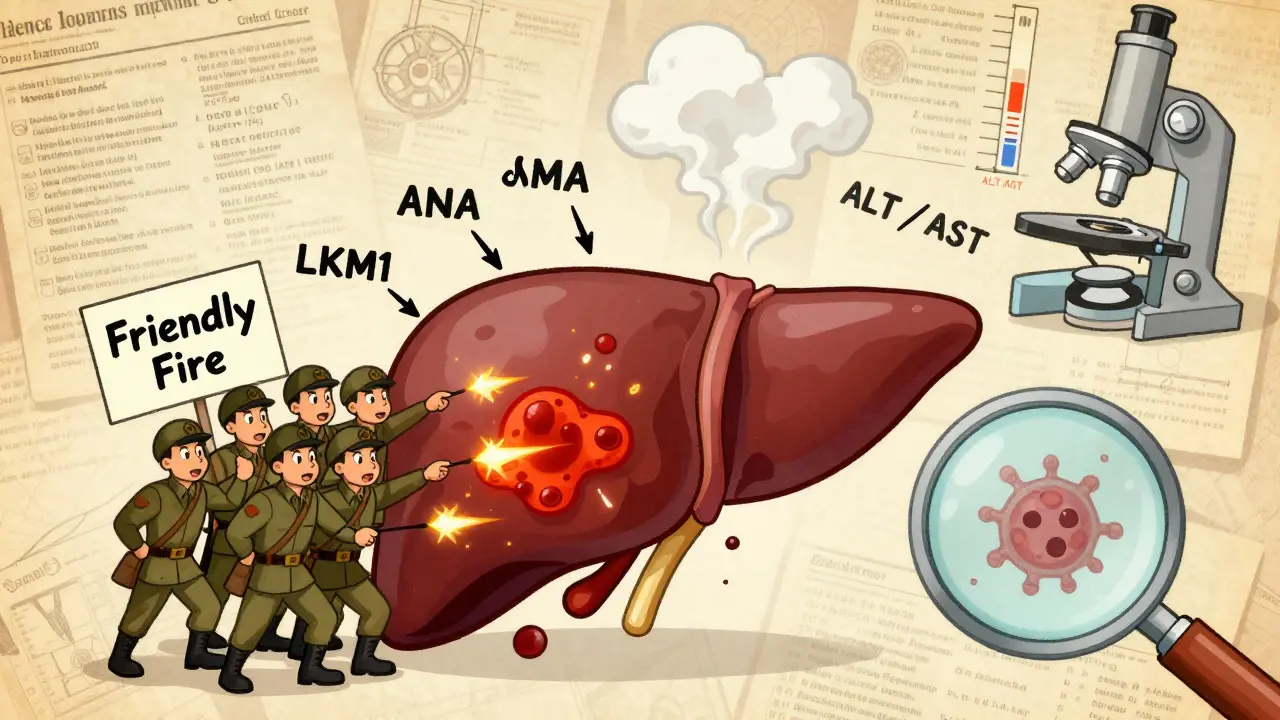

Not everyone processes medications the same way. Two people taking the same dose of a generic antidepressant or blood thinner can have wildly different outcomes. One feels better. The other gets sick. The difference? Genetics. Your genes control how fast your liver breaks down drugs. Some people have versions of genes that make them metabolize medications too quickly-so the drug leaves their system before it can work. Others break it down too slowly, causing toxic buildup. These variations are called pharmacogenes. The most common ones involve enzymes in the cytochrome P450 family, especially CYP2D6 and CYP2C9. CYP2D6 handles about 25% of all prescription drugs, including common antidepressants like sertraline and paroxetine. Over 80 different versions of this gene exist worldwide. If you’re a poor metabolizer, even a standard dose can cause serotonin syndrome. If you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer, the drug might not work at all. These aren’t guesses. They’re measurable, documented biological facts.Your Family’s Drug History Is a Clue

If your mother had a bad reaction to a generic version of warfarin, or your father needed three different painkillers before finding one that worked, that’s not coincidence. It’s inheritance. Warfarin, a blood thinner, is one of the best-studied examples. The FDA now recommends genetic testing before prescribing it. Two genes-CYP2C9 and VKORC1-determine how much warfarin you need. People of African descent often need higher doses than those of European or Asian descent, not because of weight or diet, but because of inherited genetic variants. A 2023 Mayo Clinic study found that 42% of patients who got preemptive genetic testing had at least one high-risk gene-drug interaction. In two-thirds of those cases, doctors changed the medication or dose-and adverse events dropped by 34%. Same goes for chemotherapy drugs like 5-fluorouracil. If you have a DPYD gene variant, your body can’t break it down. Standard doses cause life-threatening toxicity. One patient on Reddit shared that after a $250 genetic test showed the variant, her oncologist cut her dose from 1,200 mg/m² to 800 mg/m². She finished chemo without severe side effects. Her mother had died from the same drug years earlier-no one knew why.Genetic Differences Across Populations

Your ancestry matters. Not because of stereotypes, but because of real, measurable genetic differences. About 15-20% of Asians are poor metabolizers of proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole) due to CYP2C19 variants. That means the drug doesn’t work well for them. In contrast, only 2-5% of Caucasians have this issue. In Sub-Saharan African populations, a variant in the HMGCR gene makes pravastatin less effective. A 2024 study comparing Tunisian and Italian populations found that certain gene variants linked to metformin intolerance were far more common in one group than the other. This isn’t about race. It’s about genetic ancestry. And it’s why blanket dosing doesn’t work. A doctor prescribing the same generic statin dose to a patient of Thai descent and one of Nigerian descent might be doing harm to one of them-without even knowing it.

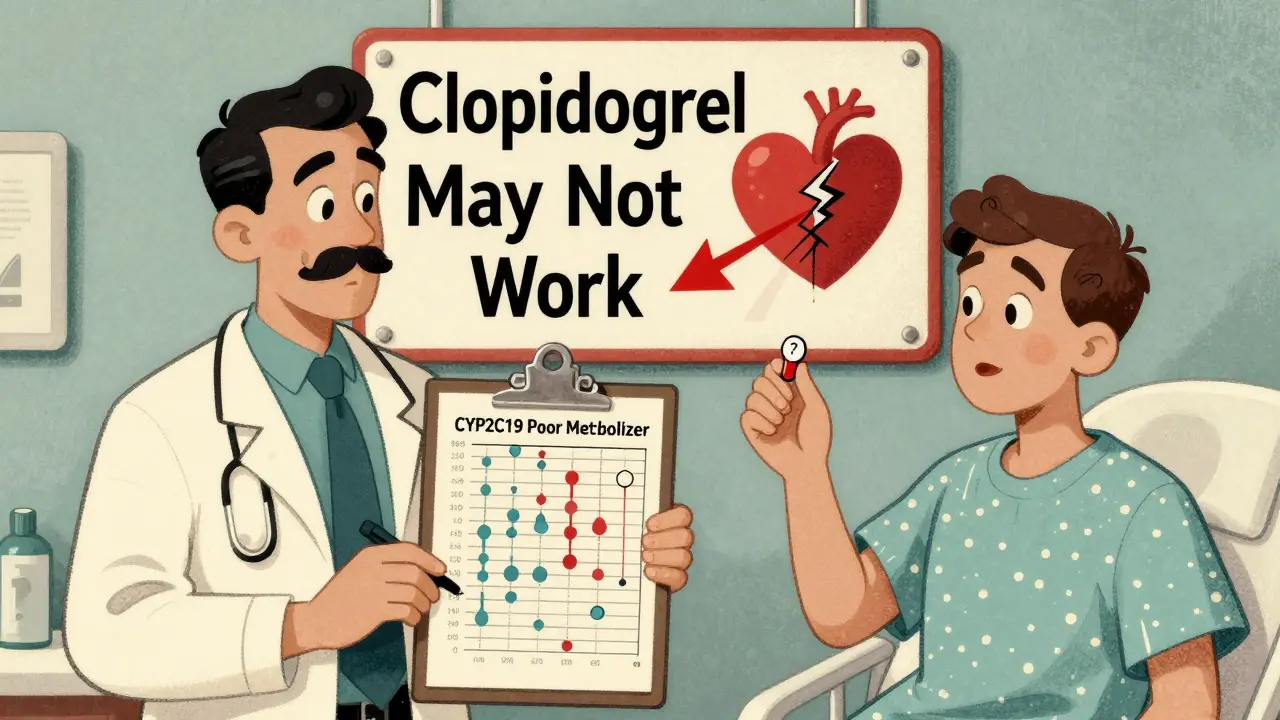

What Happens When You Switch to a Generic?

Generics are required by law to have the same active ingredient, strength, and dosage form as the brand-name drug. But they can have different fillers, coatings, or manufacturing processes. For most people, that doesn’t matter. For people with certain genetic profiles, it might. Take clopidogrel, a generic blood thinner. About 30% of people have a CYP2C19 variant that prevents their body from activating the drug. The brand and generic versions are chemically identical-but if your body can’t convert it, neither works. You’re at risk for a heart attack or stroke. This isn’t a failure of the generic. It’s a failure of one-size-fits-all prescribing. A 2023 study of 10,000 patients who got preemptive genetic testing found that 67% of those with high-risk gene-drug interactions had their medications adjusted. That’s not just a stat. That’s someone avoiding hospitalization.Testing Is Available-But It’s Not Routine

You can get tested. Companies like Color Genomics and OneOme offer panels that check 10-20 key genes for drug response. Costs range from $249 to $499. Some insurance plans cover it, especially if you’re on high-risk meds like warfarin, thiopurines, or certain antidepressants. The problem? Most doctors don’t ask. A 2022 survey of 1,247 clinicians found that while 68% felt confident reading CYP2D6 results, only 32% felt comfortable interpreting HLA-B*15:02 results linked to carbamazepine reactions. And 79% said they didn’t have time to use the data. Electronic health records are slowly catching up. Epic Systems now includes automated alerts for 12 high-priority gene-drug pairs. Vanderbilt’s PREDICT program has tested over 167,000 patients since 2012. Twelve percent had actionable results. That’s tens of thousands of people who avoided serious side effects because someone looked at their genes before prescribing.What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for a doctor to order a test. Here’s what you can do today:- Look at your family’s medication history. Did anyone have a bad reaction to a generic drug? Did a relative need multiple tries to find a working antidepressant or painkiller? Write it down.

- Ask your pharmacist. Pharmacists are trained in drug interactions. Ask if your current meds have known genetic risks. Mention if you have a family history of adverse reactions.

- Check the FDA’s list. Over 300 drug labels now include pharmacogenetic info. Look up your meds at the FDA’s Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers.

- Consider testing if you’re on high-risk drugs. Warfarin, clopidogrel, thiopurines (for Crohn’s or leukemia), and certain antidepressants are top candidates.

The Future Is Personalized-Even for Generics

The goal isn’t to stop using generics. It’s to make sure the right person gets the right dose of the right drug-no matter the brand. By 2025, 92% of academic medical centers plan to expand pharmacogenomic testing. The NIH spent $127 million on this research in 2023, with a focus on underrepresented populations. The All of Us program aims to return genetic results to 1 million Americans by 2026. Polygenic risk scores-using hundreds of genes instead of just one or two-are already showing better accuracy in predicting warfarin needs than older methods. We’re moving from guessing to knowing. Your genes don’t change when you switch from brand to generic. But your doctor might not know that. If you’ve had a bad reaction to a generic-or if your family has-don’t assume it’s just bad luck. It might be biology. And biology can be understood.Common Questions About Genetic Testing and Generic Drugs

Can generic drugs work differently because of genetics?

Yes. Generic drugs contain the same active ingredient as brand-name versions, but your body’s ability to process that ingredient depends on your genes. If you’re a poor or ultra-rapid metabolizer due to variants in genes like CYP2D6 or CYP2C19, you might not get the same effect-even if the pill looks identical.

Is genetic testing covered by insurance?

Sometimes. Medicare covers certain pharmacogenomic tests under its Molecular Diagnostic Services Program, especially for drugs like warfarin or thiopurines. Private insurers vary. Many cover testing if you’ve had a bad reaction or are starting a high-risk medication. Always check with your provider before testing.

What if my doctor won’t order a genetic test?

You can order direct-to-consumer tests from companies like Color Genomics or 23andMe (with health reports). Bring the results to your doctor. Many clinics now use tools like PharmGKB and CPIC guidelines to interpret results. If your doctor is unfamiliar, ask for a referral to a clinical pharmacist or pharmacogenetics specialist.

Are there side effects from genetic testing?

No. Genetic testing for drug response uses a simple saliva or blood sample. There’s no physical risk. But the results can be emotionally complex. Learning you have a gene variant that increases risk for a bad reaction might cause anxiety. That’s why counseling is recommended with some tests.

How long do genetic test results last?

Forever. Your genes don’t change. Once you know your pharmacogenetic profile, it applies to every medication you take now and in the future. Keep a copy and share it with any new doctor or pharmacist.

Can I use my genetic results for over-the-counter drugs?

Yes. Even common OTC drugs like ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and some sleep aids are metabolized by CYP enzymes. If you’re a poor metabolizer, you might build up dangerous levels. If you’re ultra-rapid, they might not help. Your genetic profile applies to all drugs-prescription or not.

Katherine Carlock

So basically if your mom couldn't handle generic ibuprofen, you probably shouldn't trust it either? That makes so much sense. I never thought about family history like this.

Jennifer Phelps

I took generic sertraline and felt like a zombie for 3 weeks then switched back to brand and boom energy returned like magic my doctor said it was placebo but my body knew better

Sona Chandra

THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS FALLING APART NO ONE TESTS FOR GENES THEY JUST GIVE YOU GENERIC PILLS AND SAY GOOD LUCK MY COUSIN DIED FROM A GENERIC CHEMO DRUG AND THE DOCTOR SAID IT WAS JUST BAD LUCK LMAO

Prachi Chauhan

Genetics isn't destiny but it's the silent script written before we're born. If your liver enzyme is a slowpoke, no amount of willpower fixes that. The body doesn't care about corporate cost-cutting. It just reacts. And we're treating biology like it's a software bug we can patch with a placebo.

Pharmacogenomics isn't sci-fi-it's the quiet revolution no one talks about until someone ends up in the ER because a pill didn't work the same way it did for their cousin in Ohio.

We measure cholesterol, blood pressure, glucose-but ignore the enzymes that actually process the drugs? That's like giving someone a key and refusing to check if the lock matches.

My grandmother took warfarin for 12 years. Never had an issue. My aunt got the same dose. Internal bleeding within days. Same drug. Different genes. Same hospital. Different outcomes.

The FDA knows this. The NIH knows this. But the system? It's still stuck in the 1980s. One size fits all. Except it doesn't. Not anymore. Not ever really.

It's not about race. It's about ancestry. It's about lineage. It's about the silent inheritance we never asked for but carry in every cell.

My CYP2C19 is slow. I found out after a bad reaction to clopidogrel. My dad had a stent. He died of a clot. No one tested him. No one asked. Now I get tested before every new med. It's not paranoia. It's survival.

Generics are fine. But they're not magic. They're chemistry. And chemistry doesn't care about your insurance plan. It only cares about your DNA.

We need to stop treating medicine like a grocery store aisle. You can't just grab the cheapest bottle and hope it works. Some of us need the right key. And we're not asking for luxury. Just a chance to not die because someone didn't look at the label on the inside of our cells.

beth cordell

OMG I JUST REALIZED MY MOM HAD THE SAME REACTION TO GENERIC PAINKILLERS 😭 I’M GETTING TESTED TOMORROW 🙏💊 #pharmacogenomics

Lauren Warner

Let me get this straight-you’re blaming the system for not testing everyone’s DNA before prescribing? That’s not medicine, that’s sci-fi bureaucracy. The cost alone would bankrupt the healthcare system. People die from overdoses, not because of bad genetics-they die because they don’t follow instructions. Stop making everything about genes. It’s lazy.

Jose Mecanico

I’ve been a pharmacist for 18 years. I’ve seen this over and over. Two patients, same script, same dose, one fine, one in the ER. We don’t always have the tools, but we’re starting to ask more questions. It’s not perfect, but we’re moving.

Alex Fortwengler

They’re lying. This is all Big Pharma’s plan. They want you to pay for tests so you’ll keep buying their expensive brand-name drugs. Generics are fine. It’s just your body being weak. Stop falling for the genetic fear-mongering. The government’s just trying to control you.

jordan shiyangeni

It is profoundly irresponsible that the medical establishment continues to operate under the assumption of homogeneity in drug metabolism. The fact that we are still prescribing warfarin without mandatory CYP2C9/VKORC1 screening in 2025 is not negligence-it is institutional malpractice. The data has been available since the early 2000s. The guidelines have been published by CPIC and the FDA. The infrastructure exists in academic centers. Yet, in the majority of community practices, clinicians still operate on intuition and anecdote. This is not just a failure of education-it is a moral failure. Families are being broken by preventable adverse events because someone, somewhere, decided that cost savings outweighed biological reality. And now we are expected to be grateful for a pill that might kill us? No. We deserve better. We demand better. And if the system won’t change, then we must bypass it. Get tested. Educate your providers. Share your results. Your genome is not optional.

Abner San Diego

Why are we even talking about this? In America, we don’t need genetic testing-we need better doctors. If your meds don’t work, fire your doc. My cousin took generic Xanax and got dizzy? He switched to a new doctor. Done. No tests. No drama. Just a better prescriber. This whole gene thing is just a distraction. We got real problems.

Eileen Reilly

ok so like i took generic lexapro and felt like a robot and my friend took the brand and said it was fine so i thought i was just weak but then i found out my mom had the same issue with prozac?? like wtf why does no one tell you this??

Monica Puglia

Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen so many patients suffer because no one asked about family reactions. I started asking my patients: ‘Has anyone in your family ever had a bad reaction to a med?’ It changes everything. One woman told me her sister died from 5-FU. We tested her-DPYD variant. Dose changed. She’s now in remission. This isn’t futuristic. It’s basic human care.

❤️

Cecelia Alta

Ugh, another ‘your genes are special’ article. Everyone’s got a cousin who had a bad reaction. That doesn’t mean the whole system is broken. Most people are fine on generics. Stop making everyone feel like they’re broken just because they’re not genetically perfect. Also, testing costs money. Not everyone can afford it. So now we’re supposed to blame doctors for not giving everyone a $500 genetic test? Get real. This is just guilt-tripping people into buying more services. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s not this dystopian nightmare you’re painting. Some people just need to take a pill and shut up.

jordan shiyangeni

And yet, despite the overwhelming evidence, we still treat patients as statistical averages. We don’t test because it’s ‘not cost-effective.’ But how much does it cost when someone has a stroke because clopidogrel didn’t work? When someone dies from 5-FU toxicity because no one asked about their mother’s death? When a child is born with a gene variant that makes them vulnerable to a drug their parent took for years? We don’t calculate those costs. We calculate paperwork. That’s the real tragedy.