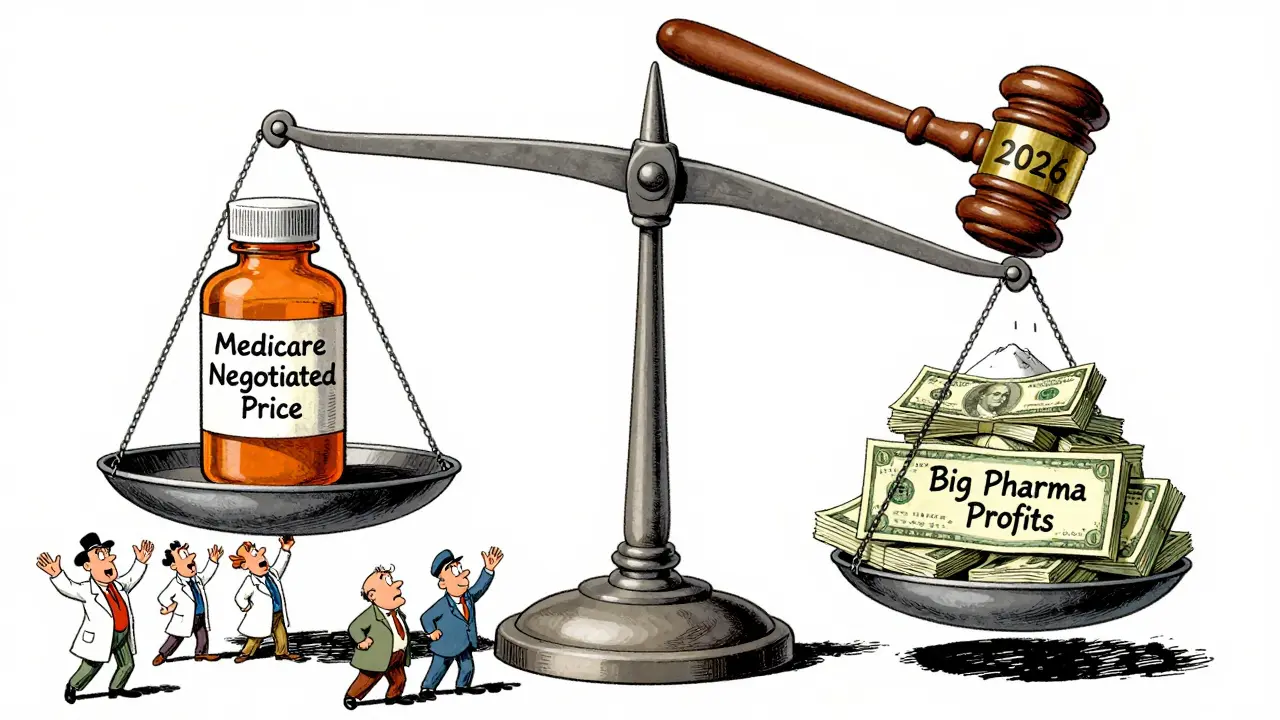

For decades, Medicare couldn’t negotiate drug prices. That changed in 2022, when the Inflation Reduction Act gave the federal government the power to step in and set fair prices for the most expensive prescription drugs. Starting January 1, 2026, this new system is finally kicking in-and it’s already cutting prices by as much as 79% for some of the most commonly used medications.

What’s Actually Changing?

Before this law, Medicare had to accept whatever price drugmakers set. Private insurers could negotiate discounts behind the scenes, but Medicare was locked out. That meant seniors paid more, and taxpayers footed the bill for high list prices. Now, for the first time, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) can directly negotiate with drug companies. They pick the drugs with the highest spending and no generic or biosimilar competition. The first 10 drugs selected include Eliquis (for blood clots), Jardiance (for diabetes), and Xarelto (another blood thinner). These drugs cost Medicare over $50 billion in 2022 alone.The goal isn’t to slash prices to zero-it’s to bring them down to what’s fair. CMS uses a formula based on what other payers pay, how many people use the drug, and whether there are similar treatments available. The final price, called the Maximum Fair Price (MFP), must be lower than the drug’s average market price. For the first round, CMS offered initial prices ranging from 38% to 79% below what drugmakers were charging. Five companies agreed during meetings. The other five agreed after written offers. No one got to keep their old price.

How the Negotiation Process Actually Works

It’s not a backroom deal. It’s a legal process with strict deadlines and public records. Here’s how it played out for the first 10 drugs:- On February 1, 2024, CMS sent each drugmaker an initial price offer, with a written explanation of how they calculated it.

- Drugmakers had exactly 30 days to respond with a counteroffer.

- CMS then held three formal negotiation meetings with each company between March and July 2024.

- By August 1, 2024, all negotiations had to end. The final prices were published on August 16, 2024.

- Starting January 1, 2026, those prices become the new standard for all Medicare Part D plans.

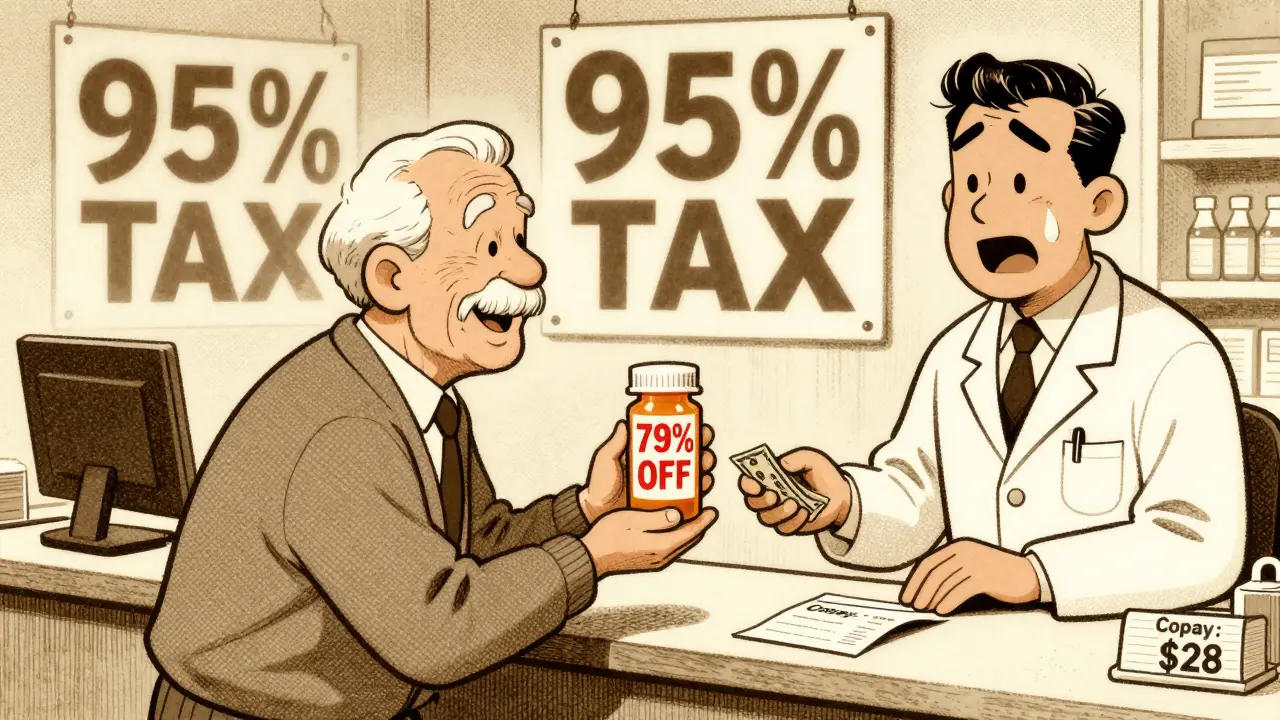

Manufacturers can’t just say, “We won’t sell it for less.” If they refuse to negotiate, they face a steep penalty: a 95% tax on all U.S. sales of that drug. That’s not a threat-it’s a legal requirement. So far, all 10 companies participated. Four of them sued, claiming the law is unconstitutional. A federal judge dismissed those lawsuits in August 2024. Appeals are expected, but the process continues.

What This Means for Your Out-of-Pocket Costs

If you’re on Medicare and take one of these 10 drugs, your costs will drop-sometimes dramatically. For example, Eliquis (apixaban), which cost over $500 a month before negotiations, is now priced at a 79% discount. That could mean your monthly copay drops from $150 to under $30, depending on your plan.But here’s the catch: not everyone feels the savings the same way. If you’re in the “donut hole” (the coverage gap), you’ll see immediate relief because your out-of-pocket costs are based on the negotiated price. If you’re in the catastrophic phase, your 5% coinsurance will still be based on the lower price, so you save too-but the change might not feel as big because you were already paying less.

Some people worry they’ll be forced to switch drugs. CMS says they’ll keep the same formularies unless the negotiated drug is the only option. If your doctor prescribed Eliquis and it’s now cheaper, you’ll likely keep it. But if your plan had a cheaper alternative, they might move you. You’ll get a notice by October 15, 2025, telling you what’s changing.

Why This Matters Beyond Medicare

This isn’t just about Medicare. Private insurers are watching closely. When the government sets a new benchmark price, companies often adjust their own contracts to match. That’s called “spillover pricing.” Stanford Medicine estimates private insurers could save $200-250 billion over the next decade because of this ripple effect. That means even if you get your drugs through an employer plan, you might see lower prices too.Drugmakers say this will hurt innovation. They argue that if they can’t charge high prices, they won’t invest in new drugs. But the Office of Management and Budget says those claims are exaggerated. The real threat isn’t to innovation-it’s to profit margins. The first 10 negotiated drugs represent less than 2% of all prescription drugs, and only 27% of small-molecule drugs even qualify for negotiation (they have to be at least 7 years old with no generics). So most new drugs won’t be affected for years.

What’s Coming Next

The program isn’t stopping. In 2027, 15 more drugs will be added. In 2028, it expands to Part B drugs-those given in doctor’s offices, like injections for arthritis or cancer. That’s a bigger shift because doctors get paid a percentage of the drug’s price. When the price drops, their reimbursement drops too. That’s why some physician groups are pushing back. They’re worried about losing income. CMS is working on new payment models to help practices adjust.By 2029, 20 drugs will be negotiated every year. That means more savings. More transparency. More pressure on drugmakers to stop raising prices every year just because they can.

What You Should Do Now

If you take one of the first 10 negotiated drugs, you don’t need to do anything yet. But here’s what you can do to prepare:- Check your Medicare Part D plan’s formulary in October 2025. You’ll get a notice in the mail.

- Compare your current copay to the projected price. You might be surprised how much you save.

- If you’re on a high-cost drug not on the list yet, keep an eye out. More drugs will be added every year.

- If you’re on a non-Medicare plan, ask your insurer if they’ll match the Medicare price. Many already do.

This isn’t a magic fix. It won’t bring down the price of every drug overnight. But it’s the first real step in the U.S. to say: enough. We’re not going to pay whatever the drug company demands. We’re going to pay what’s fair. And for millions of seniors, that’s already making a difference.

Which drugs are affected by Medicare’s new price negotiations?

The first 10 drugs selected for negotiation in 2026 are: Eliquis (apixaban), Jardiance (empagliflozin), Xarelto (rivaroxaban), Farxiga (dapagliflozin), Linagliptin, Lantus (insulin glargine), Enbrel (etanercept), Stelara (ustekinumab), Revlimid (lenalidomide), and Imbruvica (ibrutinib). These are all high-cost, single-source drugs with no generic alternatives. Starting in 2027, 15 more drugs will be added, and in 2028, the program will expand to include Part B drugs given in clinics.

Will my Medicare premiums go down because of this?

Not directly. Your monthly Part D premium is based on overall plan costs, not just drug prices. But lower drug costs mean plans will have less financial pressure, which could slow future premium increases. Some plans may even reduce premiums slightly in 2026 as a result of the savings. The biggest benefit you’ll see is in your copays and out-of-pocket costs at the pharmacy.

Can I still get my brand-name drug if it’s negotiated?

Yes. The negotiation doesn’t remove your access to the drug-it just lowers the price. If your doctor prescribed Eliquis or Jardiance, you’ll still get it. Your plan might even prefer it now because it’s cheaper. You won’t be forced to switch unless your plan already had a cheaper alternative on file. You’ll be notified if any changes affect your coverage.

Why are some drug companies suing over this?

Four drugmakers sued, claiming the negotiation law violates the Constitution by taking their property without fair compensation. They argue that setting a price they didn’t agree to is unconstitutional. A federal judge dismissed those lawsuits in August 2024, saying the government has the right to regulate pricing in public programs. The companies are appealing, but the law remains in effect. The lawsuits are delaying nothing-negotiated prices are still going into effect January 1, 2026.

Does this affect people who don’t have Medicare?

Yes, indirectly. When Medicare sets a new price for a drug, private insurers often follow suit to keep their own costs down. This is called “spillover pricing.” Experts estimate private insurers could save $200-250 billion over 10 years because of this. So even if you get your drugs through an employer plan, you may see lower prices or smaller increases in your copays. Some pharmacies are already lowering cash prices for these drugs to stay competitive.

What happens if a drugmaker refuses to negotiate?

They face a 95% tax on all U.S. sales of that drug. That’s not a suggestion-it’s a legal penalty. So far, all 10 manufacturers chose to negotiate. Refusing would mean losing almost all their revenue from that drug in the U.S. market. It’s not a viable business option. Even companies that sued still participated in negotiations.

Will this lead to fewer new drugs being developed?

The drug industry claims it will, but evidence doesn’t support that. The law only applies to drugs that are at least 7 years old (or 11 for biologics) and have no generic competition. That means new, innovative drugs aren’t affected for years. The Congressional Budget Office and the Office of Management and Budget both say the program won’t hurt innovation. Most R&D spending goes toward early-stage research, not pricing on older drugs. The real impact is on profit margins, not discovery.

Blair Kelly

This is the most important healthcare reform in a generation. Drug companies have been laughing at us for decades - charging $500 for a pill that costs $5 to make. Now they’re crying foul? Good. Let them sue. The public won’t be bullied anymore.

They claim this will kill innovation? Bullshit. Most of these drugs were developed with taxpayer-funded research. Now we’re finally getting a return on our investment. And guess what? The sky isn’t falling. People aren’t dying because Eliquis is cheaper - they’re living longer because they can afford it.

Let’s not forget: these negotiations only apply to drugs with no generics. That’s 2% of all prescriptions. The rest? Still overpriced. But this? This is the crack in the dam. And I’m here for it.

They’ll try to scare you with ‘slower innovation’ - but innovation isn’t about raising prices every year. It’s about science. And science doesn’t need $10,000-a-pill profit margins to thrive.

Mark my words: this will become the global standard. Europe already does this. Canada does it. Now we’re catching up. The only ones upset? The same CEOs who get bonuses for jacking up insulin prices. They’re not losing money - they’re losing their entitlement.

Gaurav Meena

This is HUGE 😊

From India, I’ve seen how expensive these drugs are - even for middle-class families. I remember my uncle paying $300/month for Jardiance. Here in the US, you’re finally doing something right. This isn’t just about Medicare - it’s about justice.

Hope this inspires other countries too. If America can do it, so can we. Keep going, US! 🙌

And to the drug companies: stop treating patients like ATMs. We’re not your profit center. We’re your neighbors, your parents, your friends.

Jodi Olson

There is a moral dimension here that transcends economics

When a life-saving medication is priced beyond reach, the market has failed

It is not a product like a smartphone or a pair of sneakers

It is a biological necessity

And yet for decades we allowed corporations to treat it as such

This is not socialism

This is basic human decency

The government is not setting prices arbitrarily

It is correcting a systemic failure

And for the first time in decades

We are seeing accountability

Not punishment

But fairness

That is all

Carolyn Whitehead

Just got my Part D notice and my Eliquis copay dropped from $140 to $28 😭

I didn’t even know this was happening until I saw the letter

Feeling so much less stressed now

My mom’s on Jardiance too - she’s gonna be so happy

Thanks to whoever made this happen 🙏

Still can’t believe it’s real

Katie and Nathan Milburn

The notion that this will reduce innovation is a myth propagated by industry lobbyists.

The Congressional Budget Office has repeatedly found no meaningful impact on R&D investment.

Moreover, the 10 drugs targeted represent less than 1.8% of total Medicare Part D spending.

The majority of pharmaceutical R&D is directed toward novel compounds, not price optimization of mature products.

Furthermore, the 7-year exclusivity window ensures that truly innovative drugs remain protected.

The claim that this policy will stifle innovation is not empirically supported.

It is a rhetorical device designed to maintain rent-seeking behavior.

The real threat is to profit maximization, not to scientific advancement.

Beth Beltway

Oh please. You think this is about fairness? It’s about control.

They picked the 10 most profitable drugs - the ones with the highest revenue - and now they’re forcing companies to cut prices to the bone.

What’s next? Will they start negotiating the price of your insulin? Your chemo? Your cancer drug? What if the next round includes a drug that only works for one rare disease?

Then what? You’ll force the company to sell it at a loss? And who pays when they stop making it?

This isn’t negotiation - it’s extortion.

And don’t tell me about ‘spillover pricing.’ That’s just the government setting a price ceiling and pretending it’s not.

Next thing you know, the VA will be setting prices for your private insurance too.

This is the slippery slope. And you’re all cheering it on.

Marc Bains

As someone who’s worked in global health for 15 years, I’ve seen this play out in other countries.

Canada, Germany, Australia - they’ve been negotiating drug prices for decades.

And guess what? Innovation didn’t stop.

People still got their meds.

Companies still made money.

But now, instead of 80% of the cost going to shareholders, 30% goes to patients.

This isn’t anti-business.

This is pro-human.

And if you think this is the end of American pharma, you’re not paying attention.

We’re not killing innovation.

We’re just stopping the exploitation.

Let’s be clear: no one is stopping companies from making great drugs.

They just can’t charge $500 for a pill that costs $5 to make.

That’s not socialism.

That’s basic math.

kate jones

Let’s clarify the regulatory framework: under 42 U.S.C. § 1395w-114, CMS is statutorily mandated to select drugs based on expenditure volume and lack of generic/biosimilar competition.

The Maximum Fair Price (MFP) is calculated using a weighted average of international reference prices, U.S. private payer data, and volume-adjusted cost-per-unit metrics.

Penalties for non-participation are codified under 42 U.S.C. § 1395w-114(i)(3) - a 95% excise tax on net sales, not a ‘fine.’

Legal challenges under the Fifth Amendment were dismissed on standing grounds - the plaintiffs lacked concrete injury, as they retained pricing autonomy for non-selected drugs.

Spillover effects are empirically documented: a 2023 JAMA study showed a 22% average price reduction in private insurance formularies following CMS announcements.

This is not price control - it’s evidence-based cost containment.

And yes, it’s working.

Rob Webber

They’re calling this ‘fair pricing’? What a joke.

These companies spent billions developing these drugs. Now the government comes in and says, ‘We’ll pay you 20% of what you asked for.’

That’s not negotiation. That’s confiscation.

And don’t give me that ‘taxpayer-funded research’ crap - the government didn’t build the labs, hire the scientists, or take the risk.

They just showed up at the end and demanded a cut.

Next they’ll come for your phone, your car, your house.

This is the beginning of the end.

And you people are clapping like it’s a victory.

It’s not.

It’s tyranny dressed up as compassion.

owori patrick

From Nigeria - I want to say thank you.

My sister died because she couldn’t afford her diabetes meds.

Here, we pay $500 for a month’s supply of insulin.

It’s not about politics.

It’s about people.

If the U.S. can do this, maybe we can too.

Don’t let them scare you with ‘innovation’ talk.

What’s the point of innovation if no one can use it?

I hope this spreads.

Peace.

Claire Wiltshire

For those concerned about access: CMS has explicitly stated that all negotiated drugs will remain on formularies without prior authorization barriers.

Additionally, the Inflation Reduction Act mandates that manufacturers must offer discounts to low-income beneficiaries even if they opt out of negotiation - which none did.

Furthermore, the 2026 implementation date allows sufficient time for plan adjustments and patient education.

No patient will be abruptly switched or denied access.

This is a carefully structured, phased transition - not a disruption.

And the savings are real: projected $160 billion in Medicare savings over ten years.

That’s not a threat.

That’s responsibility.

Darren Gormley

LOL at the ‘spillover pricing’ hype 😂

Private insurers are already negotiating better deals than Medicare ever could - why would they follow the government’s lowball offer?

Also, ‘79% discount’? That’s the difference between $500 and $100 - not $500 and $105.

And you think this won’t make companies pull drugs from the U.S. market?

Wait till 2028 when they hit the cancer drugs.

Then watch the shortages roll in.

And don’t get me started on how this will kill startups.

They’re not mad about profits - they’re mad about being treated like a public utility.

Next thing you know, the government will set the price of your coffee.

😂