Why Sodium Levels Matter When Your Kidneys Aren’t Working Right

Your kidneys don’t just filter waste-they’re the main control center for keeping sodium and water in balance. When kidney function drops, even small changes in how much you drink or eat can throw off your sodium levels. Two dangerous conditions can follow: hyponatremia (low sodium) and hypernatremia (high sodium). Together, they affect up to 25% of people with moderate to advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD), and they’re linked to higher hospital stays, falls, confusion, and even death.

Many patients don’t realize their symptoms-like feeling dizzy, confused, or unusually tired-are tied to sodium levels, not just fatigue from kidney disease. And here’s the twist: the very dietary advice meant to protect your kidneys can sometimes make sodium problems worse.

What’s the Difference Between Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia?

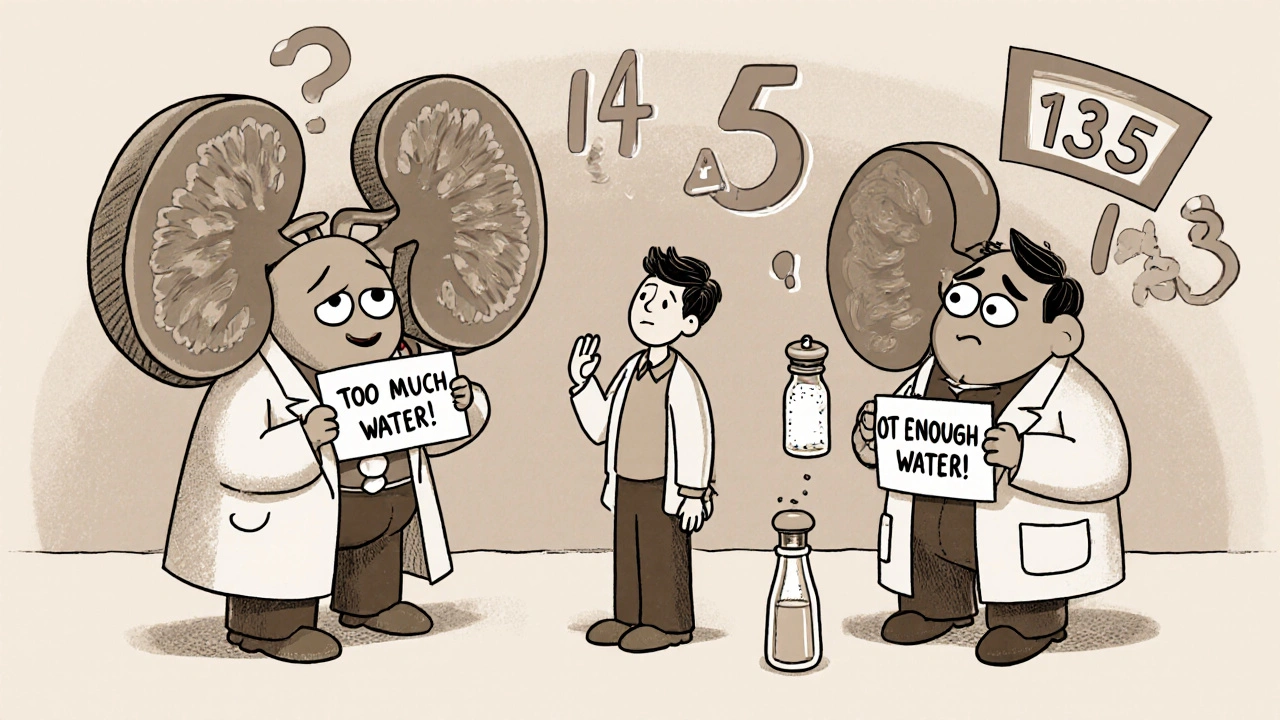

Sodium is measured in millimoles per liter (mmol/L). Normal levels sit between 135 and 145. When it drops below 135, you have hyponatremia. When it climbs above 145, it’s hypernatremia.

Hyponatremia doesn’t mean you’re low on salt overall-it means you have too much water relative to sodium. Your blood gets diluted. Hypernatremia is the opposite: not enough water, so sodium gets too concentrated.

In healthy people, your kidneys adjust urine output to fix this. But in CKD, that system breaks down. By stage 4 or 5 (eGFR below 30), your kidneys can’t make strong urine to flush out excess water or concentrate it when you’re dehydrated. That’s why both conditions show up more often as kidney disease progresses.

Why Do CKD Patients Get Hyponatremia So Often?

About 60-65% of hyponatremia cases in CKD are euvolemic-meaning your total body fluid is normal, but you’re holding on to too much water. This happens because:

- Your kidneys can’t dilute urine properly, even when you drink a lot.

- Medications like thiazide diuretics (common for high blood pressure) become more dangerous as kidney function drops. They reduce sodium reabsorption but don’t help you get rid of water.

- ADH (vasopressin), the hormone that tells your kidneys to hold water, stays active even when it shouldn’t.

- Dietary restrictions on protein, potassium, and sodium can reduce solute intake. Less solute means less ability to excrete water-even if you’re drinking the same amount.

A 2023 Japanese study found that patients on strict low-sodium, low-protein diets for CKD had higher rates of hyponatremia. Why? Less salt and protein in the diet = less solute in the urine = kidneys can’t flush out water effectively. It’s a paradox: the diet meant to help ends up trapping water.

When Does Hypernatremia Happen in Kidney Disease?

Hypernatremia is less common but just as dangerous. It usually shows up when:

- You’re not drinking enough, especially if you’re elderly or have trouble remembering to hydrate.

- You have diarrhea, vomiting, or fever and can’t replace fluids.

- You’re on medications that increase water loss, like osmotic diuretics (mannitol) or high-dose loop diuretics.

- Your kidneys can’t concentrate urine, so even small fluid losses lead to sodium buildup.

Older adults with CKD are especially at risk. They often have a weaker thirst signal, so they don’t feel thirsty even when they’re dehydrated. A simple 24-hour period without fluids can push sodium levels dangerously high.

How Dangerous Are These Conditions?

Hyponatremia isn’t just a lab number-it’s a red flag for serious outcomes:

- People with mild hyponatremia have nearly double the risk of dying (hazard ratio 1.94) compared to those with normal sodium.

- One in four hyponatremic patients over 65 experience falls. That’s nearly twice the rate of people with normal sodium.

- Cognitive decline, bone fractures, and osteoporosis are all more common.

- Even getting hyponatremia while in the hospital raises your death risk by 28%.

Hypernatremia is even more acute. If sodium rises too fast, your brain cells shrink. If you correct it too fast later, they swell. Either way, brain damage can happen. That’s why correction must be slow: no more than 10 mmol/L in 24 hours.

How Do Doctors Diagnose These Problems?

It’s not just about checking sodium. Doctors look at three things:

- Plasma osmolality-measures how concentrated your blood is. Low osmolality confirms hyponatremia is due to too much water.

- Volume status-are you swollen (hypervolemic), normal (euvolemic), or dehydrated (hypovolemic)?

- Urine sodium and osmolality-helps figure out if your kidneys are working right or if something else (like a hormone problem) is causing the imbalance.

For example: If your urine sodium is high but you’re not on diuretics, it might mean your kidneys are trying to get rid of sodium but can’t handle the water load. That’s a classic CKD pattern.

What’s the Right Treatment?

There’s no one-size-fits-all fix. Treatment depends on how fast sodium changed, how sick you are, and your kidney function.

For Hyponatremia in CKD:

- Fluid restriction is the first step. Most people with advanced CKD need to limit fluids to 800-1,000 mL per day-less than a standard water bottle. That’s hard to follow, but it works.

- Stop or switch diuretics. Thiazides are risky below eGFR 30. Loop diuretics like furosemide are safer and more effective.

- Don’t use vaptans. These drugs block ADH and help with hyponatremia in other patients-but they don’t work well in advanced CKD and can cause liver damage.

- Sodium supplements (4-8 grams/day) may help if you have a salt-wasting syndrome, which affects 5-8% of late-stage CKD patients.

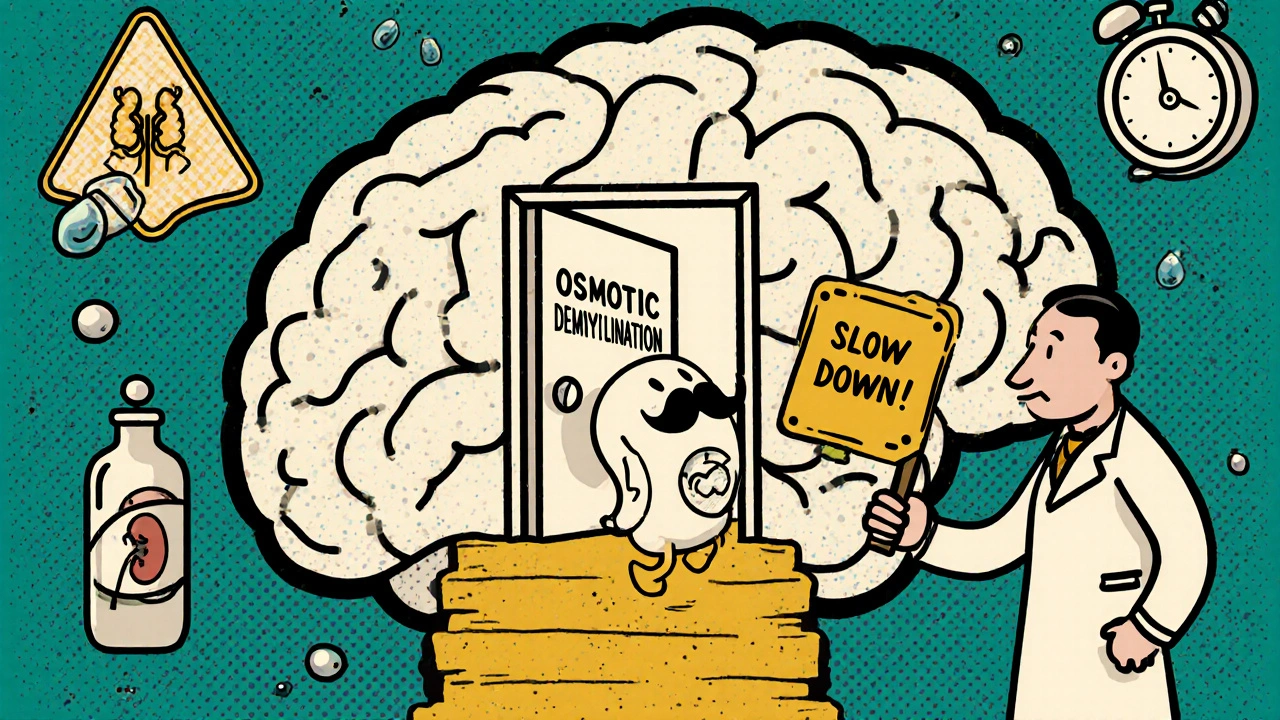

- Correction speed matters. Never raise sodium more than 4-6 mmol/L in 24 hours. Too fast can cause osmotic demyelination-a rare but devastating brain injury.

For Hypernatremia in CKD:

- Slow, controlled water replacement is key. Give fluids over 48 hours if possible.

- Oral water is best if you can drink. If not, use half-normal saline (0.45%) IV.

- Avoid rapid correction. Fixing sodium too quickly can cause cerebral edema and seizures.

Why Diet Advice Can Backfire

Many patients with CKD are told to eat low sodium, low potassium, and low protein. That’s good for controlling blood pressure, potassium levels, and acidosis. But when you cut all three, you reduce the solutes your kidneys need to excrete water.

Think of it like this: Your kidneys need salt and protein to “pull” water out of your body. Less solute = less water excretion = hyponatremia.

A 2020 study found that 22% of hyponatremia cases in stage 4-5 CKD were caused by patients over-restricting sodium and protein. They thought they were doing the right thing-until they started feeling foggy and dizzy.

Working with a renal dietitian is critical. Most patients need 3-6 sessions to learn how to balance all these restrictions without tipping into danger.

What’s New in Managing Sodium Disorders?

In March 2023, the FDA approved a new wearable patch that measures sodium levels in your skin continuously. It’s not a replacement for blood tests, but it gives early warnings when sodium starts drifting-especially helpful for people who can’t check labs often.

Also, the 2024 KDIGO guidelines are expected to recommend personalized fluid targets based on your remaining kidney function, not a one-size-fits-all number. For example, someone with eGFR 25 might need 900 mL/day, while someone with eGFR 45 might safely drink 1,300 mL.

Researchers are also looking at the gut-kidney axis. Early data suggests the intestines might help manage sodium when kidneys fail-opening up new treatment paths down the line.

What You Can Do Right Now

- If you have CKD, ask your doctor to check your sodium level at least twice a year-even if you feel fine.

- Keep a daily fluid log. Write down everything you drink, including coffee, soup, and ice.

- Don’t assume “low sodium” means “no sodium.” Your body still needs some. Talk to a dietitian about the right balance.

- Watch for symptoms: confusion, nausea, headaches, muscle cramps, or sudden fatigue. Don’t brush them off as “just getting older.”

- Make sure your pharmacist knows all your meds. Some blood pressure pills, antidepressants, and pain relievers can worsen sodium imbalances.

The bottom line: Sodium disorders in kidney disease aren’t rare. They’re predictable, preventable, and treatable-if you know what to look for.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can drinking too much water cause hyponatremia in kidney disease?

Yes. In advanced kidney disease, your kidneys can’t get rid of excess water fast enough. Drinking more than 800-1,000 mL per day can dilute your sodium, especially if you’re also on a low-solute diet. Even normal amounts of water can become dangerous if your kidney function is below 30 mL/min/1.73m².

Is low sodium always bad for people with kidney disease?

Not always. Some people with CKD have high blood pressure and benefit from reducing sodium. But going too low-below 1,500 mg per day-can reduce solute intake and make hyponatremia more likely. The goal isn’t zero sodium. It’s balance: enough to control blood pressure without starving your kidneys of the solutes they need to excrete water.

Why are thiazide diuretics dangerous in advanced kidney disease?

Thiazides work in the part of the kidney that stops working when eGFR drops below 30. They lose their ability to lower blood pressure and instead cause sodium and water loss without helping the kidneys excrete water properly. This leads to hyponatremia. The FDA warns against using them in patients with eGFR under 30.

Can I fix hypernatremia by just drinking more water?

Not if you have advanced kidney disease. Your kidneys may not be able to concentrate urine or hold onto water properly. Drinking more might not help-and if you drink too fast, it can cause brain swelling. Always correct hypernatremia slowly under medical supervision.

How often should I get my sodium levels checked?

If you have stage 3 or higher CKD, check sodium every 3-6 months. If you’re on diuretics, have had a previous sodium imbalance, or are over 65, check every 2-3 months. Don’t wait for symptoms-many people don’t feel anything until it’s serious.

Swati Jain

Okay, so let me get this straight-your kidneys are basically the sodium bouncer at a club, and when they quit, the water crashes the party while sodium gets locked out? 🤯 This is why I stopped telling my nephro patient to chug water like it’s a hydration challenge. Also, thiazides in eGFR <30? That’s like giving a toddler a chainsaw. 💀

David vaughan

I... I didn't realize that low sodium diets could cause hyponatremia... 😳 I mean, I thought 'less salt = better'... but now I'm like... wait, so the diet is the problem? That's... that's kinda wild. I need to re-read this. Maybe talk to my dietitian. 😅

David Cusack

The notion that solute intake governs free water excretion is not novel-it’s been textbook nephrology since the 1970s yet somehow this post acts as if it’s breaking news. The real tragedy is that patients are still being misinformed by non-specialists who think 'low sodium' means 'zero sodium'. The KDIGO guidelines have been clear for years. Why are we still having this conversation?

Elaina Cronin

I find it deeply concerning that this information is not being systematically integrated into primary care protocols. Patients with CKD are being discharged with dietary instructions that are not only incomplete but actively hazardous. This is not an isolated case-it is a systemic failure of education, communication, and accountability. We must demand better.

Willie Doherty

Data point: A 2023 retrospective cohort of 1,842 CKD patients showed that those on <1,500 mg sodium/day had a 3.2x higher incidence of hyponatremia compared to those on 2,000–2,500 mg/day (p<0.001). The paradox is quantifiable. The solution? Not more restriction. More precision. And no, 'just drink less water' isn't a strategy-it's a cop-out.

Darragh McNulty

You’re not alone, David! 💪 This stuff is confusing AF but you’re already ahead just by asking questions. 🙌 Talk to your dietitian-seriously, they’re wizards. I had a buddy with stage 4 CKD who thought ‘no salt’ meant ‘no flavor’… until he started eating broth with a pinch of sea salt and suddenly stopped passing out in the shower. 🚿✨ Small tweaks. Big wins.

Cooper Long

The cultural disconnect between Western dietary dogma and physiological reality is profound. In many societies, sodium is not a villain-it is a necessity. The one-size-fits-all approach to CKD nutrition ignores ethnic, socioeconomic, and metabolic diversity. We need context, not commands.

Sheldon Bazinga

so like... ur kidneys are broke so u stop drinking water?? lol that’s why ppl get dumb in old age?? i mean i knew kidney ppl were weird but this is next level. also why tf are we still using 1990s diet rules?? 🤡

Sandi Moon

Let’s not ignore the elephant in the room: the pharmaceutical-industrial complex profits from chronic mismanagement. Vaptans are expensive. Diuretics are cheap. Fluid restriction? Free. But who gets funded? Who gets studied? Who gets marketed to doctors? The answer isn’t in the labs-it’s in the boardrooms.

Kartik Singhal

LMAO this is why I stopped trusting Western medicine. First they tell you to cut salt, then they tell you cutting salt kills you. Then they say ‘oh but don’t drink too much water’-so what am I supposed to do? Eat rocks? 😂 The whole system is a scam. I’m just gonna drink tea and ignore everything. 🤷♂️

Logan Romine

We treat kidneys like broken toasters-swap the part, reboot the system. But the body isn’t a machine. It’s a symphony. And sodium? It’s not just a number. It’s the rhythm. When the kidneys falter, the whole orchestra stumbles. We don’t fix sodium-we try to conduct chaos. And we’re all just guessing which note to play next.

Mark Kahn

Seriously though-this is gold. If you have CKD, go see a renal dietitian. Like, right now. Not next month. Not when you feel bad. Now. They’ll help you eat real food without turning your sodium into a minefield. You don’t need to be perfect-just informed. And you’re not alone. 🙏