When someone is diagnosed with multiple myeloma, the focus often turns to chemotherapy, stem cell transplants, or new targeted drugs. But for more than 80% of patients, the most painful and life-limiting problem isn’t the cancer itself-it’s the damage it does to their bones. Think of it this way: your bones aren’t just passive scaffolding. In multiple myeloma, they become a battlefield where cancer cells hijack the body’s natural repair system and turn it into a weapon. The result? Holes in the bones, fractures from minor bumps, spinal cord compression, and constant pain that no amount of painkillers can fully fix.

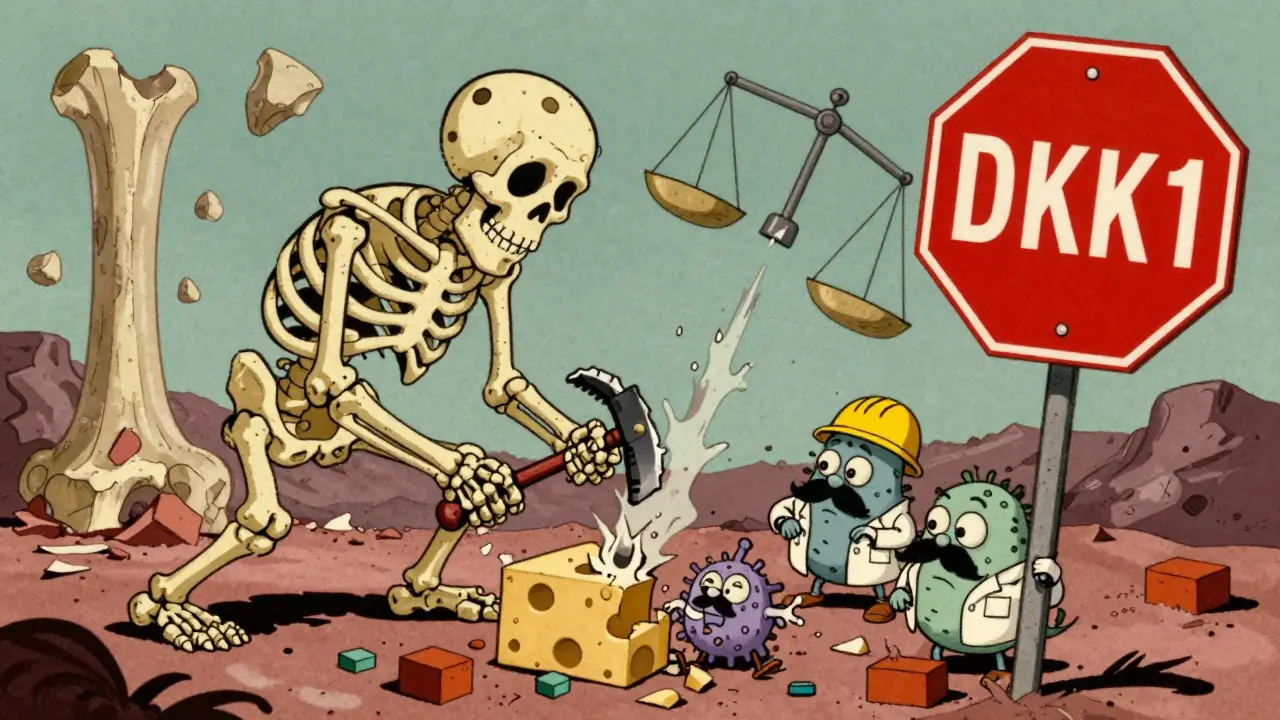

How Myeloma Turns Bones Into Swiss Cheese

Normal bone is always being broken down and rebuilt. Osteoclasts chew away old bone. Osteoblasts lay down new bone. In healthy people, these two teams work in sync. In multiple myeloma, that balance shatters. Myeloma cells flood the bone marrow and start sending out chemical signals that crank up osteoclast activity while shutting down osteoblasts. It’s like having a demolition crew on 24/7 and no construction crew at all.

The most visible sign? Osteolytic lesions-punched-out holes in bones seen on X-rays or CT scans. These aren’t random. They form right where myeloma cells cluster. One key player is the RANKL protein. Myeloma cells and nearby bone cells produce way more RANKL than normal, which tells osteoclasts to go wild. At the same time, levels of OPG, the natural brake on RANKL, drop. The RANKL/OPG ratio can be 3 to 5 times higher in myeloma patients than in healthy people.

But it’s not just RANKL. Myeloma cells also pump out DKK1 and sclerostin-two proteins that block the Wnt signaling pathway, which osteoblasts need to grow and repair bone. Patients with DKK1 levels above 48.3 pmol/L have more than three times as many bone lesions as those with lower levels. Sclerostin, meanwhile, averages nearly 28.7 pmol/L in myeloma patients versus 19.3 pmol/L in healthy individuals. Even osteocytes, the most numerous bone cells, get pulled into the chaos, sending signals that worsen bone destruction.

This isn’t just a one-way street. As bone breaks down, it releases growth factors trapped in the bone matrix-like IGF-1 and TGF-beta-that feed the myeloma cells. So the more the bone is destroyed, the more the cancer grows. And the more the cancer grows, the more bone it destroys. That’s the vicious cycle doctors talk about.

The Standard Tools: Bisphosphonates and Denosumab

For decades, the go-to treatments have been bisphosphonates-zoledronic acid or pamidronate-given as monthly IV infusions. These drugs stick to bone surfaces and kill off overactive osteoclasts. They’ve been shown to reduce skeletal-related events (SREs) like fractures and spinal cord compression by about 15-18% compared to no treatment.

Then came denosumab, a monoclonal antibody that directly blocks RANKL. It’s given as a monthly shot under the skin. In clinical trials, it was just as effective as zoledronic acid at preventing SREs, with fewer kidney problems. That’s a big deal for myeloma patients, many of whom already have kidney damage from the disease. A 2021 Mayo Clinic study found that 74% of patients preferred denosumab over IV bisphosphonates because of the convenience and lower risk of kidney strain.

But here’s the catch: neither drug rebuilds bone. They only slow the destruction. So even if you’re on treatment, your bones stay weak. And over time, some patients develop medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ)-a rare but serious condition where the jawbone starts to die. About 42% of patients on long-term bisphosphonates or denosumab report needing dental procedures because of it.

Other side effects are common too. About 31% of patients get acute phase reactions after IV bisphosphonates-fever, chills, muscle aches. Hypocalcemia (low calcium) affects 18.5% of patients. And for those with kidney issues, dose adjustments are needed in 22% of cases.

The New Wave: Drugs That Don’t Just Stop Damage-They Heal

The real breakthrough isn’t just stopping bone loss. It’s getting bones to heal. That’s where the next generation of drugs comes in.

One of the most promising is romosozumab, an anti-sclerostin antibody. By blocking sclerostin, it wakes up osteoblasts and lets them start rebuilding bone. In a 2021 phase II trial with 49 myeloma patients, romosozumab boosted bone mineral density in the spine by 53% over 12 months. Patients also reported a 35% improvement in pain scores. The FDA is now funding a phase III trial called BONE-HEAL, which will enroll 450 patients to see if this translates into fewer fractures and better survival.

Another contender is DKN-01, which targets DKK1. In a 2020 trial with 32 patients, it cut bone resorption markers by 38%. That means less bone breakdown. Early results suggest it may work best when combined with other myeloma drugs.

Then there’s nirogacestat, a gamma-secretase inhibitor that blocks the Notch pathway-a key driver of osteoclast activation. In animal models, it reduced bone lesions by 62%. Human trials are just beginning, but the potential is clear: a drug that targets the tumor and the bone at the same time.

Even though these drugs are exciting, they’re not without risks. Anti-sclerostin therapies can cause low calcium, so patients need monthly blood tests. Gamma-secretase inhibitors often cause rashes in over two-thirds of users. And because they’re new, long-term safety data is still limited.

Who Gets What-and Why It Matters

Not every patient gets the same treatment. Cost, access, and kidney function play huge roles.

In the U.S., denosumab is used in 78% of cases. It’s more expensive-$1,800 per dose-but easier to administer. In Europe, only 42% of patients get it, mostly because of reimbursement rules. In Asia, bisphosphonates still dominate, used in 89% of cases, partly because they’re cheaper and generics are widely available.

For patients with kidney problems, denosumab is often the better choice. For those who can’t afford it, zoledronic acid remains a solid option. But for younger patients with aggressive bone disease, doctors are starting to consider novel agents-even outside of clinical trials-when standard therapy isn’t enough.

There’s also a growing push to test bone turnover markers early. If a patient’s DKK1 or sclerostin levels are sky-high, they might benefit more from a targeted agent than from a bisphosphonate. The goal? Personalize treatment before fractures happen.

What Patients Are Really Experiencing

Behind the statistics are real people living with constant pain and fear.

On the Myeloma Crowd Reddit forum, one patient wrote: “I broke my rib sneezing. I’m 42. I have two kids. I don’t want to be the guy who can’t pick them up.” Another said, “I had to get three teeth pulled because of jaw bone death. I didn’t know that was a risk when I started the drug.”

But there’s hope. Patients in romosozumab trials report being able to walk without pain for the first time in years. One woman said she started gardening again. Another, who avoided hugs for fear of breaking a bone, now holds his granddaughter.

These aren’t just clinical outcomes. They’re quality-of-life wins.

The Road Ahead: Healing, Not Just Preventing

The future of myeloma bone disease isn’t just about adding more drugs. It’s about combining them smartly. Think of it like treating heart disease: you don’t just lower cholesterol-you also lower blood pressure, stop smoking, and exercise. For myeloma, the ideal approach will combine tumor-killing agents with bone-building drugs.

Researchers are now testing bispecific antibodies that attack myeloma cells while also blocking RANKL or DKK1. RNA therapies are being developed to silence DKK1 at the genetic level. And in labs, scientists are looking at ways to use bone turnover markers to predict who will respond best to which drug.

By 2030, experts believe we’ll be able to not just prevent bone damage-but reverse it. That means fractures, spinal cord compression, and hospital stays due to bone problems could become rare. For patients, that’s not just a medical advance. It’s a return to life.

Right now, the standard of care is still bisphosphonates and denosumab. But if you or a loved one has multiple myeloma and bone pain isn’t improving, ask your doctor: Are we just slowing the damage-or are we ready to start healing?

What causes bone damage in multiple myeloma?

Bone damage in multiple myeloma happens because cancer cells disrupt the normal balance between bone breakdown and rebuilding. They overactivate osteoclasts (cells that break down bone) through proteins like RANKL and suppress osteoblasts (cells that build bone) by releasing DKK1 and sclerostin. This leads to osteolytic lesions-holes in the bone-and weakens the skeleton, making fractures and pain common.

Are bisphosphonates still the best option for myeloma bone disease?

Bisphosphonates like zoledronic acid are still widely used and effective at reducing fractures and other bone complications. But they don’t rebuild bone, and they can harm the kidneys. For many patients, especially those with kidney issues, denosumab is now preferred because it’s given as a shot and doesn’t affect kidney function. Newer agents like romosozumab are showing promise in rebuilding bone, so treatment is shifting from just prevention to actual repair.

What is denosumab and how is it different from bisphosphonates?

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks RANKL, a protein that triggers bone breakdown. It’s given as a monthly injection under the skin. Bisphosphonates, like zoledronic acid, are given intravenously and work by killing osteoclasts. Denosumab doesn’t affect the kidneys, making it safer for patients with kidney problems. It’s also more convenient, but it’s significantly more expensive-about $1,800 per dose compared to $150 for generic zoledronic acid.

Do any new drugs actually rebuild bone in myeloma patients?

Yes. Romosozumab, an anti-sclerostin drug, has shown in clinical trials to increase bone mineral density in the spine by 53% in myeloma patients. It works by blocking sclerostin, a protein that stops bone-building cells from working. This allows osteoblasts to rebuild bone. Other agents like DKN-01 (anti-DKK1) and nirogacestat (anti-Notch) are also being tested to not only stop bone loss but reverse it.

What are the side effects of the new bone-targeting drugs?

Anti-sclerostin drugs like romosozumab can cause low calcium levels, requiring monthly blood tests and calcium supplements. Gamma-secretase inhibitors often cause severe rashes in over 60% of patients. All bone-modifying drugs carry a small risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ), especially if dental work is done while on treatment. Patients need a dental check-up before starting any of these therapies.

How do I know if I’m a candidate for a novel agent?

If you have aggressive bone disease-multiple fractures, severe pain despite standard treatment, or high levels of DKK1 or sclerostin-you may benefit from newer agents. Ask your doctor about bone turnover markers and whether you qualify for a clinical trial. Even if you’re not in a trial, some oncologists are using these drugs off-label for patients who aren’t responding to bisphosphonates or denosumab.

Adrienne Dagg

I broke a rib sneezing 😭 I’m 42 and my kids think I’m made of glass now. This post gave me hope. Romosozumab sounds like magic. I’m begging my oncologist to put me on a trial.

Erica Vest

The RANKL/OPG ratio elevation in multiple myeloma is well-documented in the literature, with a mean increase of 3.8-fold compared to healthy controls (Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2020). Denosumab’s mechanism of action directly targets this pathway, making it pharmacologically superior to bisphosphonates in patients with preserved renal function. However, long-term suppression of bone remodeling carries inherent risks, including atypical femoral fractures and osteonecrosis of the jaw, which require proactive dental management.

Chris Davidson

All this fancy science is just corporate profit machines selling hope to desperate people. Bisphosphonates have been around for decades and they work. Why pay 1800 dollars for a shot when a generic IV costs 150. Pharma is running the show not doctors

Kinnaird Lynsey

I read the entire post and felt seen. I also had three teeth pulled because of MRONJ. No one warned me. I didn’t even know it was a thing until my jaw started crumbling. I’m glad someone finally wrote this. But I’m not holding my breath for romosozumab to be covered by insurance anytime soon.

Andrew Kelly

They say bone healing is possible now but what they’re not telling you is that every new drug is just a Trojan horse for more chemo. They want you hooked on monthly shots so they can keep billing. And don’t get me started on how they use DKK1 levels to scare you into signing up for trials. It’s all a numbers game.

Isabel Rábago

I can’t believe people still use bisphosphonates. You’re literally poisoning your kidneys for a 15% reduction in fractures. That’s not treatment. That’s gambling. And if your doctor won’t even test your sclerostin levels, find a new one. This isn’t 2010 anymore.

Anna Sedervay

The very notion that osteoblasts can be ‘reactivated’ through monoclonal antibody intervention is predicated upon a reductionist paradigm that fundamentally misapprehends the epigenetic complexity of the bone marrow microenvironment. One must consider the pleiotropic effects of Wnt pathway modulation vis-à-vis hematopoietic stem cell niche integrity-this is not a trivial pharmacological maneuver.

Jedidiah Massey

DKK1 inhibition = game changer. The gamma-secretase pathway is the real bottleneck. If you're not tracking TRAP5b and P1NP biomarkers monthly, you're flying blind. Romosozumab’s 53% BMD increase? That’s not a miracle-it’s a statistical artifact. Wait for phase III data. Or better yet, join the trial.

Alex Curran

I’ve been on denosumab for 3 years. Kidneys fine. No jaw necrosis. But I get the chills every time I get the shot. Feels like I’m getting a flu shot from hell. Still better than IVs. My spine feels stronger. I’m hiking again. Not cured. But alive. That’s enough for now.

Lynsey Tyson

My mom started romosozumab last month and she’s actually laughing again. She used to cry when she had to sit down because her back hurt. Now she’s planting tulips. I didn’t think I’d see that again. Thank you for writing this. I showed it to her doctor.

Edington Renwick

They’re selling ‘healing’ like it’s a spa treatment. Bone lesions aren’t a bad hair day. You can’t just ‘reverse’ them with a shot and call it a day. This is cancer. You’re not fixing bones-you’re delaying death. And don’t get me started on the rashes from nirogacestat. One guy I know had to be hospitalized.

Kitt Eliz

YESSSSS THIS IS THE FUTURE 🚀 Bone rebuilding isn’t sci-fi anymore. Romosozumab + anti-myeloma combo = the holy grail. I’m in a trial and my DKK1 dropped 70% in 8 weeks. My spine density is up. I’m not just surviving-I’m thriving. If you’re not asking your oncologist about bone turnover markers, you’re leaving power on the table. GO GET THAT HEALING 💪🩺