Opioid-Antihistamine Risk Calculator

Assess Your Risk

This tool calculates the combined risk of respiratory depression when opioids and first-generation antihistamines are used together based on key patient factors.

Select all options to see your risk assessment

When a patient takes an opioid‑antihistamine interaction is a dangerous pharmacodynamic combination that amplifies central nervous system depression, leading to profound drowsiness and breathing problems. The problem isn’t new, but it’s often hidden because antihistamines are sold over the counter while opioids require a prescription. This article breaks down why the mix is risky, who suffers most, and what clinicians and patients can do to keep safety first.

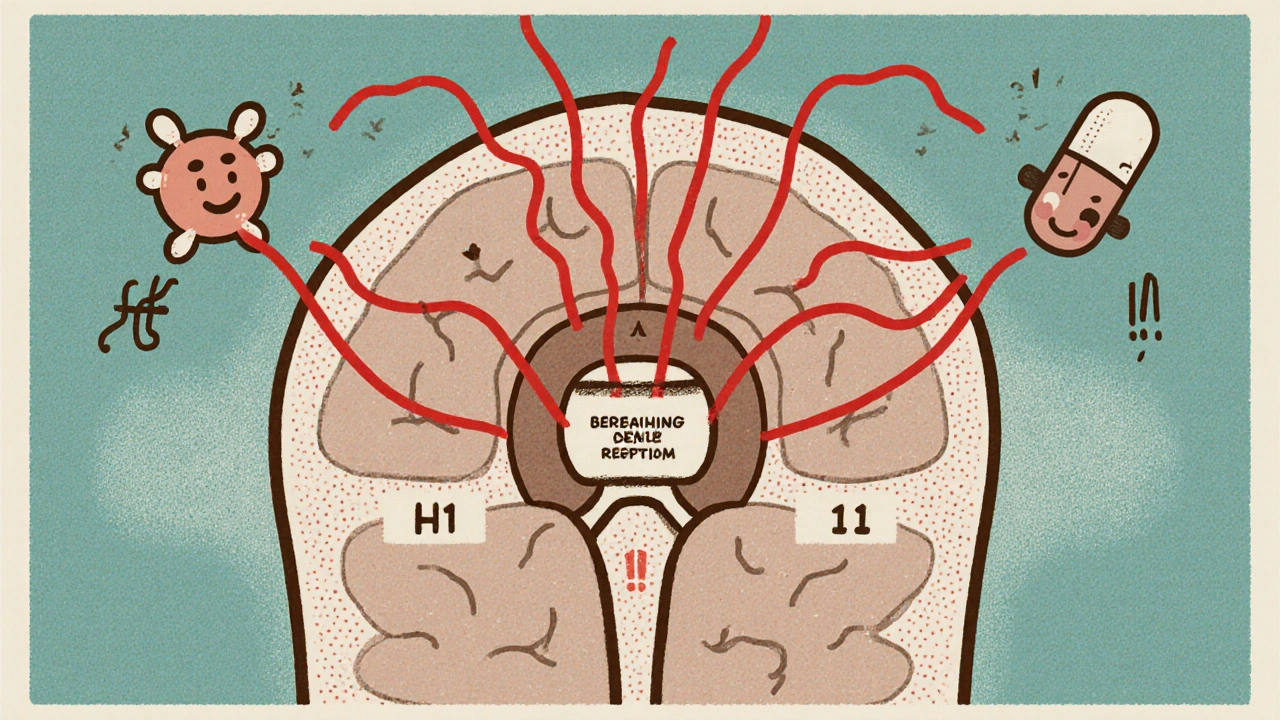

How Opioids and Antihistamines Hit the Brain

Opioids bind to mu‑opioid receptors, easing pain but also dulling the brainstem’s response to carbon dioxide. First‑generation antihistamines cross the blood‑brain barrier and block H1 receptors, producing a “sleep‑on‑pill” effect. When both drugs are present, the brain receives two separate depressant signals at the same time - a classic case of pharmacodynamic potentiation.

Key players in this drama include:

- Opioids such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, and fentanyl

- First‑generation antihistamines - diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, doxylamine

- Respiratory centers in the medulla that regulate breathing rhythm

The FDA’s 2016 safety communication warned that any CNS‑depressant added to opioids can trigger ‘extreme sleepiness, slowed breathing, coma, or death.’ While the agency highlighted benzodiazepines, the same language applies to antihistamines because they depress the same neural pathways.

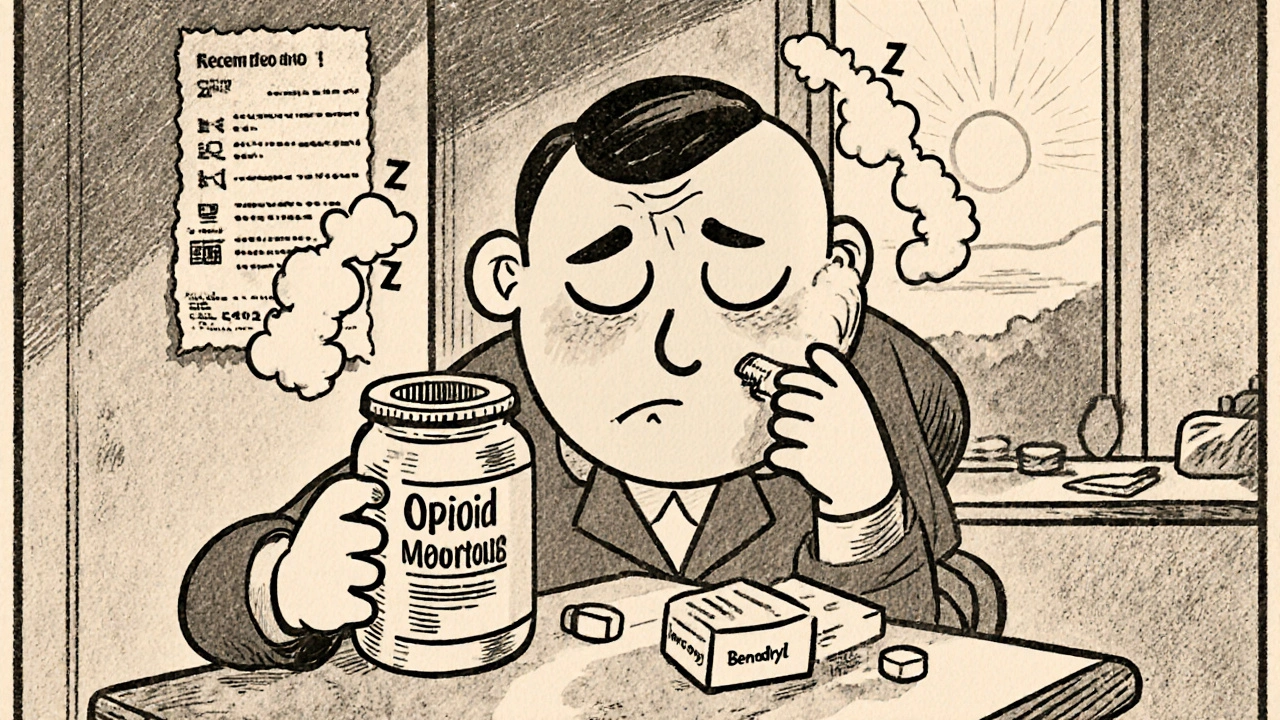

Why Sedation Turns Dangerous

Alone, opioids cause sedation in 20‑60 % of users, especially after dose escalation (AAFP, 2006). First‑generation antihistamines add another 40‑70 % chance of drowsiness, thanks to 60‑70 % brain penetration (Cleveland Clinic, 2023). Stack the two, and the odds of “excess sedation” skyrocket.

Two mechanisms drive the risk:

- Reduced ventilatory response: Opioids blunt the body’s ability to sense CO₂ buildup. Antihistamines further mute the respiratory drive by dampening neuronal firing in the brainstem.

- Anticholinergic load: Many first‑gen antihistamines have strong anticholinergic effects, which can cause dry mouth, confusion, and in the elderly, delirium that masks early respiratory decline.

Because there is no reversal agent for antihistamine‑induced CNS depression (unlike flumazenil for benzodiazepines), clinicians must rely on prevention and vigilant monitoring.

Who Is Most at Risk?

The interaction is especially perilous for:

- Older adults - Beers Criteria flags diphenhydramine as potentially inappropriate for people over 65.

- Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or sleep‑disordered breathing.

- Anyone who has taken alcohol or other sedatives on the same day.

Studies show opioid‑induced respiratory depression (OIRD) spikes within the first 24 hours after surgery, and the presence of a second CNS depressant doubles the odds of a serious event (Boon et al., 2021).

Real‑World Evidence: Numbers and Stories

Large‑scale data on opioid‑antihistamine combos are sparse, but related research paints a clear picture. A North Carolina cohort found overdose death rates ten times higher when opioids were co‑prescribed with benzodiazepines - a trend likely mirrored when antihistamines are added (FDA, 2016).

Case reports add color:

- A 68‑year‑old took hydrocodone for back pain and Benadryl for itching, became unresponsive, and spent 36 hours in ICU (Reddit, 2022).

- A patient on oxycodone fell after severe drowsiness from Atarax, fracturing a hip (PatientsLikeMe, 2021).

- Sermo’s 2023 physician survey logged 147 sedation events involving opioids + antihistamines; 32 % needed naloxone rescue.

These anecdotes echo the ISMP’s 87 reports between 2019‑2022, with 12 resulting in permanent harm or death.

Practical Steps for Clinicians

Guidelines from the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA, 2021) and CDC (2022) recommend a layered approach:

- Screen for OTC use: Ask patients specifically about antihistamines at every visit.

- Electronic alerts: Implement hard‑stop warnings in EHRs. University of Michigan saw a 42 % drop in adverse events after adding an opioid‑antihistamine flag (JAMA Intern Med, 2021).

- Limit dose & duration: When a combination is unavoidable, keep both drugs at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest time.

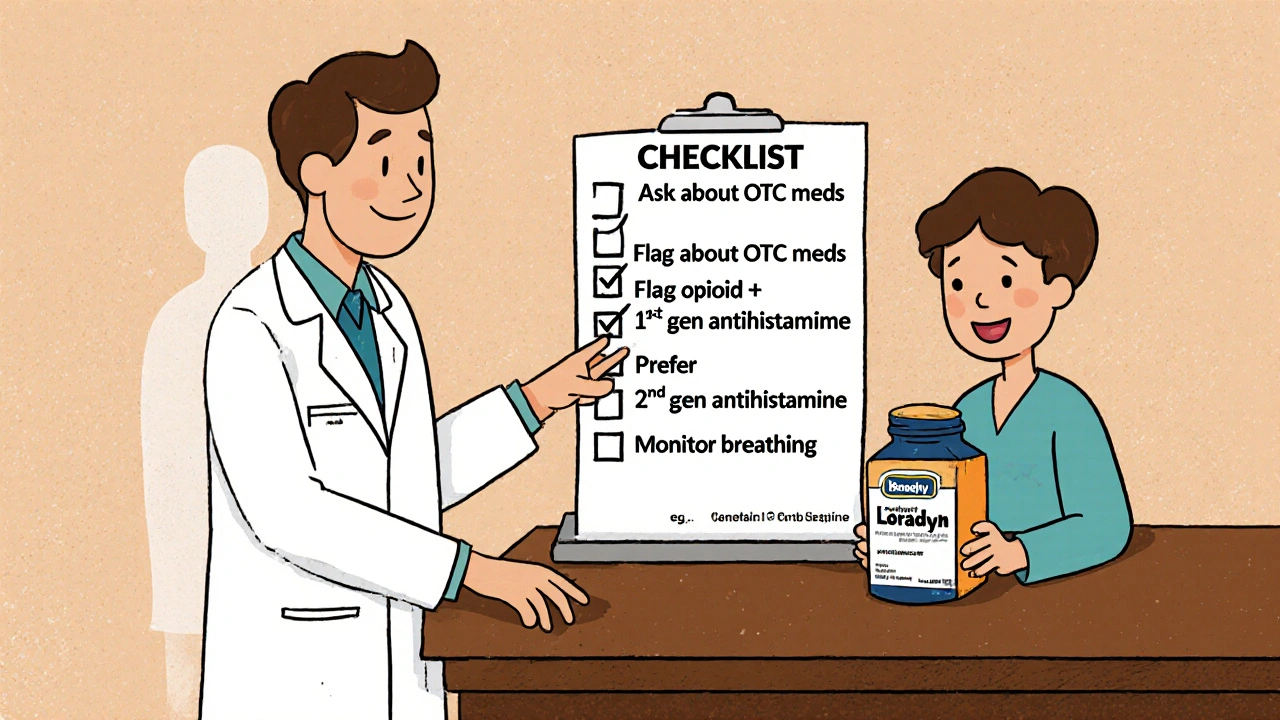

- Choose safer alternatives: Switch to second‑generation antihistamines (loratadine, fexofenadine) that have <1 % brain penetration.

- Monitor closely: Use continuous pulse‑ox and capnography for inpatients; educate outpatients to seek help if breathing slows.

Training programs are now mandatory for over 1.4 million prescribers under the FDA REMS update (2023).

Patient‑Facing Strategies

Patients can protect themselves by:

- Reading the medication guide that comes with every opioid prescription.

- Never self‑medicating with “sleep aids” that contain diphenhydramine.

- Keeping a list of all OTC drugs and sharing it with their pharmacist.

- Choosing non‑sedating allergy relief (e.g., fexofenadine) when possible.

Only 34 % of people on opioids receive comprehensive counseling about drug interactions (CDC, 2022). Raising that number is a quick win for safety.

First‑ vs Second‑Generation Antihistamines: A Quick Comparison

| Antihistamine | Generation | Brain Penetration | Typical Sedation Rating* (1‑5) | Anticholinergic Burden |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) | First | ~65 % | 4 | High |

| Hydroxyzine (Atarax) | First | ~55 % | 3‑4 | Moderate‑High |

| Loratadine (Claritin) | Second | <1 % | 1‑2 | Low |

| Fexofenadine (Allegra) | Second | <1 % | 1 | Very Low |

*Sedation rating is based on patient‑reported drowsiness in clinical trials (Cleveland Clinic, 2023).

Quick Safety Checklist for Providers

- Ask about all OTC meds at each visit.

- Flag any order that pairs an opioid with a first‑gen antihistamine.

- Prefer second‑gen antihistamines for allergy relief.

- Document counseling on sedation and breathing risks.

- Arrange post‑discharge monitoring for high‑risk patients.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take an over‑the‑counter allergy pill with my prescription opioid?

It’s risky, especially if the pill is a first‑generation antihistamine like diphenhydramine. The combination can cause severe drowsiness and breathing slowdown. Choose a non‑sedating option or talk to your doctor first.

Why are antihistamines considered CNS depressants?

First‑gen antihistamines cross the blood‑brain barrier and block H1 receptors in the brain, which leads to drowsiness, slowed reflexes, and reduced respiratory drive-classic signs of central nervous system depression.

What should I do if I notice extreme sleepiness after taking both medicines?

Call emergency services right away. Severe sedation can quickly turn into respiratory failure. If you have naloxone at home (often provided with opioid prescriptions), administer it while awaiting help.

Are there any lab tests that predict who will have a bad reaction?

Pharmacogenetic panels (e.g., Genelex Opioid Risk Panel) can flag CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 variants that affect opioid metabolism, but they don’t predict antihistamine interaction. Clinical risk factors-age, lung disease, concurrent sedatives-remain the main guide.

How do hospitals reduce these events?

Many use hard‑stop alerts in electronic health records, continuous respiratory monitoring for inpatients, and education programs that stress asking about OTC medications at admission.

Understanding the synergy between opioids and antihistamines turns a hidden hazard into a preventable one. By screening, choosing safer alternatives, and keeping patients educated, providers can dramatically cut the odds of excess sedation and life‑threatening respiratory depression.

Jeremy Lysinger

Great reminder to double‑check OTC meds when prescribing opioids. A quick ask‑about‑Benadryl can save a lot of trouble.

Andrew Wilson

People need to stop being lazy with their meds – mixing painkillers and sleepy antihistamines is just asking for trouble. It's not "just a little drowsy", it's dangerous. Wake up and read the warnings!

Shermaine Davis

I totally agree, we should all be more careful. i think a quick chat at the pharmacy could prevent a lot of scary outcomes. Sorry for any typos!

Debra Johnson

The synergistic depression of the central nervous system caused by opioids and first‑generation antihistamines is not a trivial academic footnote.

When both agents converge on the medullary respiratory centers, the ventilatory response to hypercapnia can be blunted beyond the safety margin.

This pharmacodynamic potentiation is analogous to stacking two weighted blankets on a child who already struggles to breathe.

Clinicians must therefore treat the combination as a red‑flag interaction, much like they would with benzodiazepines.

The literature demonstrates that even sub‑therapeutic doses of diphenhydramine can amplify opioid‑induced sedation.

Moreover, the anticholinergic burden contributes to xerostomia, delirium, and impaired mucociliary clearance in vulnerable patients.

The elderly population, whose cholinergic reserve is already diminished, are especially susceptible to these effects.

Respiratory depression in this cohort often masquerades as simple drowsiness, delaying crucial intervention.

Without a specific reversal agent for antihistamine‑mediated CNS depression, supportive measures become the mainstay of treatment.

Rapid assessment of respiratory rate, end‑tidal CO₂, and level of consciousness is indispensable.

Implementation of electronic health record alerts that flag opioid‑antihistamine co‑prescription has been shown to reduce adverse events.

Educational initiatives targeting both prescribers and patients can further mitigate risk by encouraging the use of second‑generation antihistamines.

Encouraging patients to disclose over‑the‑counter medication use during every encounter is a simple yet effective practice.

Pharmacy counseling at the point of sale for antihistamines should include warnings about concurrent opioid therapy.

In sum, a proactive, multidisciplinary approach is essential to prevent the silent yet deadly synergy of these two drug classes.

Joey Yap

This really makes me think about how hidden risks can slip into everyday life. The subtle anticholinergic load often goes unnoticed until it's too late.

We owe it to patients to ask gentle, non‑judgmental questions about their sleep aids.

Understanding their lived experience can reveal patterns we otherwise miss.

Lisa Franceschi

I appreciate the thoroughness of the analysis presented here. It underscores the importance of maintaining professional boundaries while offering guidance.

Diane Larson

From a practical standpoint, switching to loratadine or fexofenadine eliminates the CNS‑depressant risk entirely.

Educating patients about these alternatives can dramatically reduce sedation events.

Clinicians should incorporate this recommendation into discharge instructions.

Michael Kusold

Interesting read, I hadn't thought about OTC antihistamines being that risky. Definitely something to keep in mind.

Narasimha Murthy

Whilst the data are compelling, one must consider confounding variables such as concurrent alcohol use.

Not every patient on a benadryl‑opioid regimen will experience respiratory failure.

Nevertheless, caution is warranted.

Katherine Collins

Wow, this is eye‑opening! 😊

Taylor Nation

Exactly, a quick reminder at the pharmacy can change outcomes.

Let's push for better labeling.

Nathan S. Han

The drama of hidden dangers is real, and the stakes are life‑changing.

We must champion awareness across the care continuum.

Every clinician, pharmacist, and patient has a role.

The collective effort can turn a silent threat into a preventable story.