TB Drug Alternative Selector

Select patient factors and resistance information to get recommendations on alternative TB drugs to Ethambutol:

Key Takeaways

- Ethambutol is useful for preventing resistance but can cause vision problems.

- First‑line alternatives (Isoniazid, Rifampin, Pyrazinamide) are usually more potent but have their own toxicity profiles.

- Second‑line agents like Bedaquiline and Delamanid are reserved for drug‑resistant TB.

- Choosing a replacement hinges on efficacy, side‑effects, cost, pregnancy safety, and local resistance patterns.

- Never switch or stop drugs without consulting a TB specialist.

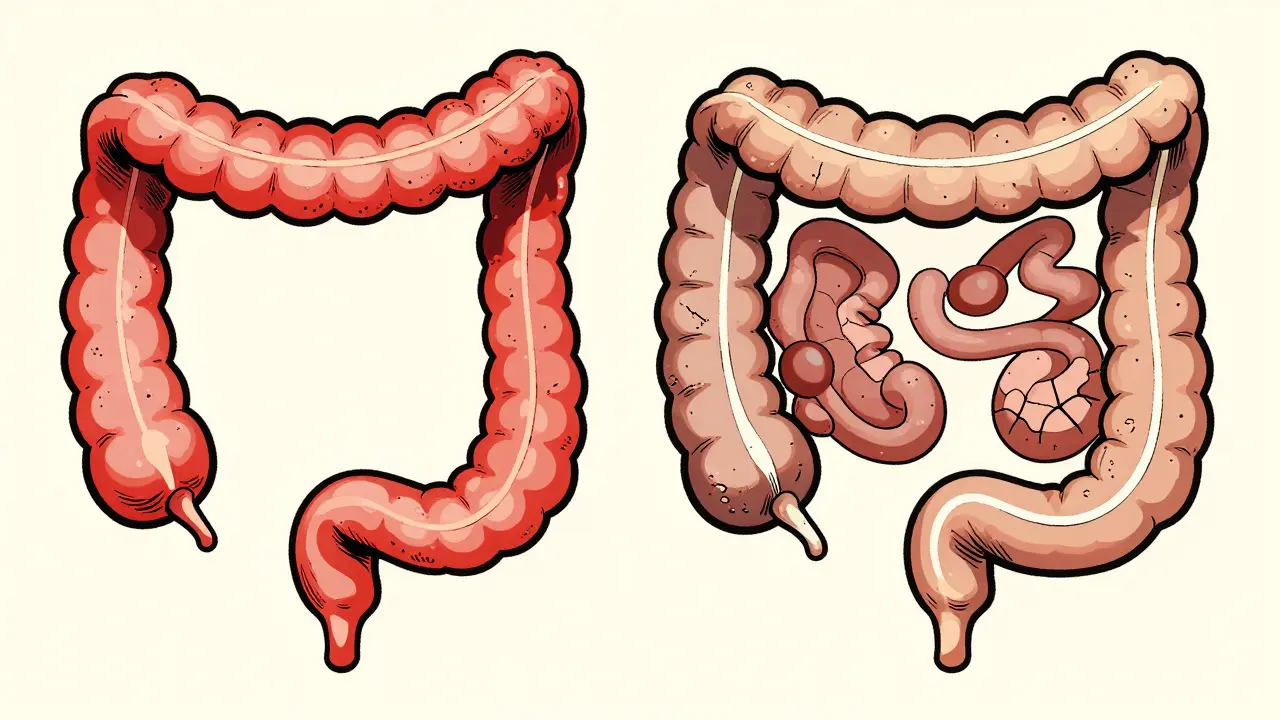

When treating active tuberculosis, Ethambutol is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with the synthesis of the mycobacterial cell wall by blocking arabinosyl transferases. It is typically combined with other first‑line drugs to prevent resistance. In many regimens it appears as the "E" in the classic 2HRZE/4HR (Isoniazid, Rifampin, Pyrazinamide, Ethambutol). Let’s see how it stacks up against the other players on the TB stage.

Ethambutol works by stopping the bacteria from building a sturdy cell wall, which slows growth but doesn’t kill the bug outright. The standard adult dose is 15‑25mg/kg daily, given once a day. It’s taken for the first two months of therapy and then usually dropped unless resistance mandates continuation.

One of the biggest drawbacks is ocular toxicity. Up to 5% of patients develop optic neuritis, presenting as blurred vision or color‑vision loss. The risk rises with higher doses, prolonged use, and renal impairment. Regular visual‑acuity testing is therefore a must.

Resistance to Ethambutol alone is relatively uncommon, but when it occurs it often signals broader multi‑drug resistance. That’s why clinicians keep an eye on susceptibility patterns before discarding it from a regimen.

Below are the most common alternatives, each introduced with a brief definition.

Isoniazid is a potent bactericidal drug that targets the synthesis of mycolic acids in the mycobacterial cell wall. It is the cornerstone of both latent‑TB treatment and the intensive phase of active disease.

Rifampin is a broad‑spectrum antibiotic that inhibits DNA‑dependent RNA polymerase, halting transcription in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It has the strongest early‑bactericidal activity among first‑line agents.

Pyrazinamide is a pro‑drug that becomes active in acidic environments, disrupting membrane energetics of dormant bacilli. It shortens the overall treatment duration.

Streptomycin is an aminoglycoside that binds the 30S ribosomal subunit, causing misreading of mRNA and bacterial death. It’s now a second‑line option due to ototoxicity and injectable administration.

Bedaquiline is a diarylquinoline that inhibits the mycobacterial ATP synthase, leading to energy collapse in resistant strains. Approved for multidrug‑resistant TB (MDR‑TB).

Delamanid is a nitro‑imidazooxazole that blocks mycolic acid synthesis, also reserved for MDR‑TB. It’s oral and works synergistically with Bedaquiline.

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, primarily affecting the lungs but capable of spreading to other organs. Effective therapy relies on a combination of drugs to prevent resistance.

| Drug | Class | Mechanism | Typical Adult Dose | Major Side Effects | Pregnancy Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethambutol | First‑line | Inhibits arabinosyl transferases (cell‑wall synthesis) | 15‑25mg/kg daily | Optic neuritis, rash, elevated liver enzymes | Category C (use if benefit outweighs risk) |

| Isoniazid | First‑line | Blocks mycolic‑acid synthesis | 5mg/kg (max 300mg) daily | Hepatotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy | Category A (considered safe) |

| Rifampin | First‑line | Inhibits RNA polymerase | 10mg/kg (max 600mg) daily | Hepatotoxicity, orange bodily fluids, drug interactions | Category C |

| Pyrazinamide | First‑line | Disrupts membrane energetics of dormant bacilli | 20‑30mg/kg daily | Hepatotoxicity, hyperuricemia | Category C |

| Streptomycin | Second‑line (injectable) | Inhibits protein synthesis (30S subunit) | 15mg/kg IM/IV daily | Ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity | Category D |

| Bedaquiline | Second‑line (MDR‑TB) | Inhibits ATP synthase | 400mg daily x2weeks, then 200mg three times/week | QT prolongation, hepatotoxicity | Category B |

| Delamanid | Second‑line (MDR‑TB) | Blocks mycolic‑acid synthesis | 100mg twice daily | QT prolongation, nausea | Category B |

Decision criteria you should weigh

- Efficacy: First‑line drugs (Isoniazid, Rifampin, Pyrazinamide) offer fastest bacterial kill. Ethambutol adds a protective shield against resistance but is less potent on its own.

- Toxicity profile: If a patient has pre‑existing liver disease, Isoniazid or Pyrazinamide may be risky, making Ethambutol or Rifampin preferable. For someone with glaucoma or color‑vision issues, avoid Ethambutol.

- Cost & availability: In low‑resource settings, the four first‑line agents are cheap and widely stocked. Bedaquiline and Delamanid are costly and often require special procurement.

- Pregnancy considerations: Isoniazid is safest; Rifampin and Ethambutol are Category C, used only when benefits outweigh risks. Streptomycin is contraindicated.

- Resistance patterns: Local labs reporting >10% Ethambutol resistance suggest dropping it in favor of a stronger partner drug or adding a second‑line agent.

Best alternative scenarios

- Visual toxicity concerns: Switch to Rifampin+Isoniazid+Pyrazinamide (HRZ) and omit Ethambutol. Add a fluoroquinolone if resistance is suspected.

- Severe liver disease: Choose a regimen of Rifampin+Streptomycin (injectable) while monitoring renal function.

- Multidrug‑resistant TB (MDR‑TB): Use Bedaquiline+Delamanid in combination with an injectable and a fluoroquinolone, reserving Ethambutol only if susceptibility is confirmed.

- Pregnant patient: Prioritize Isoniazid+Rifampin, add Ethambutol only if the strain is resistant to other agents.

- Cost‑sensitive setting: Stick with the classic 2HRZE/4HR regimen; the cheapness of Ethambutol outweighs its modest toxicity risks for most patients.

Practical tips for patients and clinicians

- Schedule baseline and monthly visual‑acuity tests when Ethambutol is part of the regimen.

- Check liver function tests before starting Isoniazid, Rifampin, or Pyrazinamide; repeat if symptoms appear.

- Ask about other medications - Rifampin induces many drug‑metabolizing enzymes, reducing effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives and antiretrovirals.

- For injectable drugs (Streptomycin), ensure proper technique to avoid nerve injury.

- When moving to Bedaquiline or Delamanid, obtain baseline ECG; monitor QT interval weekly for the first month.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I stop Ethambutol if I develop vision problems?

Yes. Discontinue Ethambutol immediately and inform your doctor. They will likely replace it with another partner drug, such as Rifampin, while continuing the rest of the regimen.

Is Ethambutol necessary for drug‑sensitive TB?

It isn’t strictly mandatory if local resistance data show low Ethambutol resistance. However, most guidelines keep it in the intensive phase because it lowers the chance of developing resistance to the other three drugs.

How does the cost of Bedaquiline compare to Ethambutol?

Bedaquiline can cost several hundred dollars per month in high‑income countries and is subsidized in many low‑resource programs. Ethambutol, by contrast, is a generic tablet that typically costs under $1 per dose.

Is there any cross‑resistance between Ethambutol and other first‑line drugs?

Cross‑resistance is rare because Ethambutol targets a different enzyme than Isoniazid, Rifampin, or Pyrazinamide. However, multidrug‑resistant strains often carry mutations that affect multiple agents simultaneously.

Can pregnant women safely take Ethambutol?

Ethambutol is Category C, meaning animal studies showed some risk but human data are limited. It’s used only when the potential benefit to the mother outweighs any possible fetal risk, typically alongside safer drugs like Isoniazid.

Keri Henderson

When you start a patient on Ethambul, the first thing you do is schedule a baseline visual acuity test; this sets a reference point for any future changes.

Next, you educate the patient on the subtle signs of optic neuritis, such as difficulty distinguishing red from green, because early detection prevents permanent loss.

Make sure the clinic has a Snellen chart or a colour‑vision test like Ishihara ready at each monthly visit.

If the patient reports any blurring, you stop Ethambul immediately and replace it with a partner drug, typically Rifampin, while keeping the rest of the regimen intact.

Document the visual findings in the chart, noting both acuity and colour discrimination scores.

For patients with renal impairment, consider dose‑adjusting Ethambul to the lower end of the 15‑25 mg/kg range to reduce toxicity risk.

Monitor liver function tests regularly if Isoniazid or Pyrazinamide are part of the regimen, because overlapping hepatotoxicity can complicate management.

When dealing with pregnant patients, weigh the Category C risk of Ethambul against the benefit of preventing resistance; often you’ll keep the drug only if the strain is resistant to other first‑line agents.

Cost‑sensitive settings can still afford Ethambul; it’s cheap, and the price of a missed visual test is far higher in the long run.

If local resistance data show >10 % Ethambul resistance, discuss with the microbiology team about dropping it in favor of a fluoroquinolone.

Always involve the patient in shared decision‑making; ask them if they understand the purpose of the visual tests and encourage them to report any changes promptly.

Consider using tele‑health video calls for quick visual checks when patients live far from the clinic, but confirm any concerns with an in‑person exam.

Stay updated on newer agents like Bedaquiline; while they’re expensive, they may replace Ethambul in MDR‑TB cases where resistance patterns shift.

Remember that adherence is king: a patient who forgets doses is more likely to develop resistance than one who tolerates mild visual side effects.

Finally, keep a low threshold for consulting a TB specialist if you encounter atypical toxicity or resistance patterns; their expertise can guide safe regimen adjustments.

elvin casimir

Yo, the article kinda blurs the line between solid guidance and a half‑baked meme‑post.

First off, Ethambul’s ocular toxicity isn’t some myth, it’s documented in peer‑reviewed journals.

Second, you can’t just swap drugs without checking local susceptibility data, that’s basic Infectious Disease 101.

Third, the cost argument is weak; cheap meds are only cheap if you factor in the cost of vision testing later.

Bottom line: follow the guidelines, stop the guesswork.

Steve Batancs

Ethambul functions by inhibiting arabinosyl transferases, thereby disrupting the mycobacterial cell wall.

Its bacteriostatic nature complements the bactericidal actions of Isoniazid, Rifampin, and Pyrazinamide.

This synergy reduces the emergence of resistance during the intensive phase.

When hepatic function is compromised, Ethambul offers a safer alternative, as it is not heavily metabolized by the liver.

Nonetheless, patients with compromised renal clearance require dose adjustment to mitigate optic neuritis risk.

In pregnant populations, the drug is categorized as C, indicating a risk‑benefit analysis is mandatory.

Overall, the decision matrix must weigh efficacy, toxicity, cost, and resistance patterns.

Ragha Vema

Listen, there’s a hidden agenda pushing Ethambul because the big pharma labs want a steady stream of cheap pills.

They hide the fact that the optic nerve damage is often reversible only if you catch it early, which they know most clinicians don’t.

Meanwhile, the newer fluoroquinolones quietly get sidelined in the guidelines.

It feels like a conspiracy, but the data on vision loss is right in front of us.

Stay vigilant, folks, and don’t let the system dictate the patient’s sight.

Scott Mcquain

It is imperative, therefore, to recognize, that cost‑effective therapy does not justify, neglecting patient safety; indeed, the cheapness of Ethambul is no excuse for inadequate monitoring!

One must, unquestionably, schedule monthly visual acuity exams, and any deviation, however minor, warrants immediate cessation of the drug!

Furthermore, the ethical duty to inform patients of potential optic neuritis, cannot be overstated, nor can the responsibility to document every ocular assessment!

When resistance patterns dictate, substituting Ethambul with a more potent partner is not merely advisable, it is morally obligatory!

Thus, the clinician’s role transcends prescription; it encompasses vigilant advocacy, relentless follow‑up, and unwavering adherence to best‑practice standards!

kuldeep singh sandhu

Honestly, Ethambul isn’t the only option, but it works.

Mariah Dietzler

i think the guide is ok but kinda long.

the tables are helpful but u could just give a quick cheat sheet.

also, i wish they mentioned the cheap generic versions more.

overall, solid info but could be more concise.

Nicola Strand

While the authors advocate retaining Ethambul in most regimens, the evidence for its necessity in drug‑sensitive TB is increasingly tenuous.

Meta‑analyses have shown that omission of Ethambul does not significantly affect sputum conversion rates when Isoniazid, Rifampin, and Pyrazinamide are administered as per standard dosing.

Therefore, in settings where visual monitoring resources are scarce, omitting Ethambul may be a pragmatic choice.

Nonetheless, local resistance surveys should guide any deviation from guideline‑recommended combinations.

In short, the drug is optional rather than indispensable.

Jackie Zheng

Great rundown! Just a quick note: the term "Ethambul" seems to be a typo-it's Ethambutol throughout the literature.

Also, remember that the visual toxicity threshold can be lower in patients with pre‑existing ocular conditions.

For those individuals, checking baseline colour vision is essential before starting therapy.

Lastly, the cost advantage is significant, especially in low‑resource programs where a single tablet can cost less than a dollar.

Keep up the thorough summaries; they’re super helpful for clinicians on the front lines.

Hariom Godhani

Let me be perfectly clear: the medical community has been lulled into a complacent rhythm by repeating the same outdated regimens year after year.

Ethambul, while historically useful, is now a relic that clings to the periphery of modern TB therapy.

When you examine the pharmacodynamics, it is merely bacteriostatic-an attribute that pales in comparison to the bactericidal prowess of Rifampin and Isoniazid.

Moreover, the risk of optic neuritis, though statistically low, carries a weighty burden for patients whose livelihoods depend on clear vision.

Imagine a fisherman in a rural setting losing colour discrimination; the socioeconomic fallout is profound.

Adding to this, the drug’s Category C classification during pregnancy raises ethical dilemmas for obstetricians making treatment decisions.

In contrast, newer agents such as Bedaquiline, despite higher costs, offer potent, targeted activity against resistant strains and do not jeopardize visual health.

Cost arguments are often weaponized by politicians to keep cheap, sub‑optimal drugs on the market, thereby maintaining a status quo that benefits pharmaceutical lobbyists.

Furthermore, the reliance on visual monitoring imposes an infrastructure demand that many low‑income clinics simply cannot meet.

Consequently, patients in those regions endure an avoidable risk that could be mitigated by either removing Ethambul or substituting it with a better‑studied partner drug.

For those advocating the retention of Ethambul, I urge a re‑evaluation of the data: systematic reviews have shown no statistically significant advantage in sputum conversion when Ethambul is included in a regimen already containing Rifampin, Isoniazid, and Pyrazinamide.

In light of these findings, the continued blanket recommendation feels more like tradition than evidence‑based practice.

Therefore, I challenge clinicians to scrutinize each prescription on a case‑by‑case basis, prioritizing patient safety over institutional inertia.

End of story.

Jackie Berry

I totally get the balancing act between efficacy, cost, and side‑effects; it’s a daily reality for us on the wards.

What helped me most was creating a simple checklist: baseline vision test, liver panel, pregnancy status, and local resistance data.

Once that was in place, adjusting the regimen became a matter of ticking boxes rather than endless debate.

I also found that involving patients in the discussion-explaining why we’re doing a vision test-boosted adherence dramatically.

In my experience, the cheapness of Ethambul shines when you have the capacity to monitor, but if you lack that, opting for a more straightforward regimen with fewer monitoring requirements can be kinder to both patient and clinic.

Bottom line: tailor the regimen to the resources at hand and keep communication open.