Blood Pressure & Kidney Disease Risk Calculator

Enter Your Health Information

Your Risk Assessment

When your blood pressure stays high for months or years, it’s not just a number on a cuff-it can silently scar the kidneys. Understanding why high blood pressure and kidney disease are linked helps you break the cycle before irreversible damage sets in.

What Is High Blood Pressure?

High Blood Pressure is a chronic condition where the force of blood against artery walls consistently exceeds the normal range (typically >130/80mmHg). Over time, the excess pressure damages blood vessels, heart, and vital organs. The condition is also called hypertension and affects roughly 1 in 3 adults in the United States.

What Is Kidney Disease?

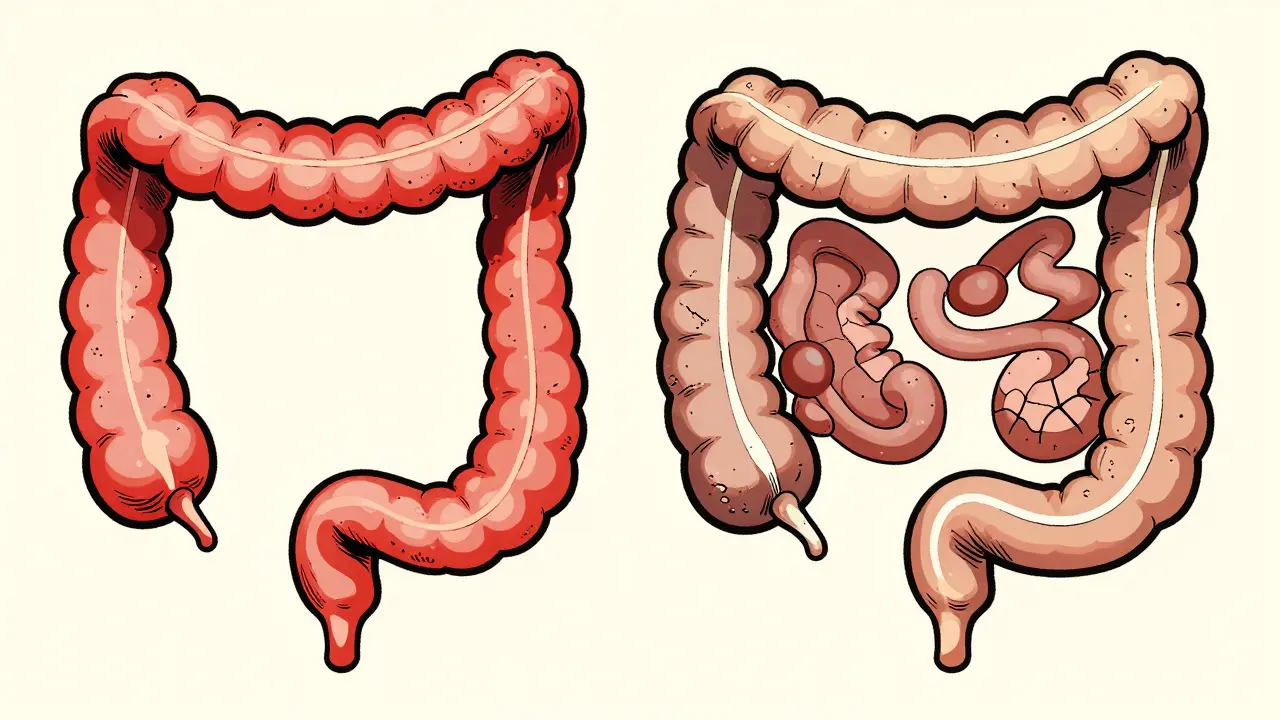

Kidney Disease refers to any long‑term loss of kidney function. When the disease progresses to a stage where the kidneys can no longer filter waste effectively, it’s termed chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD affects about 15% of U.S. adults, and many cases go unnoticed until the later stages.

How Hypertension Hurts the Kidneys

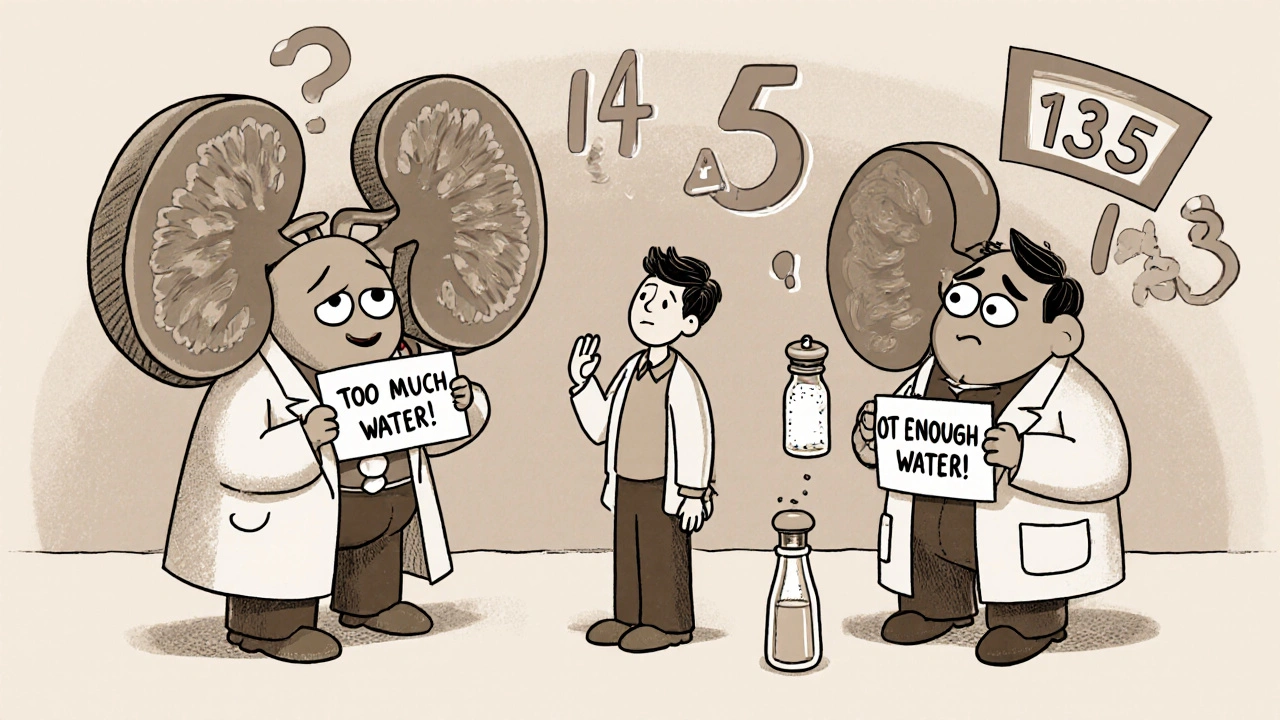

The kidneys rely on a delicate network of tiny blood vessels called glomeruli. Each glomerulus is a bundle of capillaries that filters blood, extracting waste while returning clean fluid to circulation. When blood pressure spikes, the glomerular capillaries experience higher shear stress, leading to three key problems:

- Arteriosclerosis: The walls thicken and lose elasticity, narrowing the filter’s pores.

- Protein Leakage: Damaged filters allow proteins like albumin to slip into urine, a hallmark sign called proteinuria.

- Nephron Loss: Over time, scarred nephrons drop out of service, reducing the kidneys’ overall filtering capacity.

The process is fueled by the renin‑angiotensin system (RAS), a hormonal cascade that regulates blood pressure and fluid balance. In hypertension, the RAS stays over‑active, causing blood vessels to constrict and sodium retention to increase, further raising pressure on the kidneys.

Early Warning Signs and Tests

Because kidney damage can be silent, regular screening is crucial for anyone with hypertension.

- Blood Pressure Check: Aim for < 130/80mmHg. Consistently higher readings warrant tighter control.

- Urine Albumin Test: Detects micro‑protein (albumin) that indicates early glomerular injury. Values < 30mg/g are normal.

- Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR): eGFR estimates how much blood the kidneys filter per minute. An eGFR above 90mL/min/1.73m² is healthy; below 60 suggests CKD.

- Serum Creatinine: Elevated levels signal reduced kidney clearance.

These tests together form a simple, low‑cost monitoring package that can catch damage before symptoms appear.

Lifestyle Moves That Slow the Damage

Changing everyday habits can dramatically lower both blood pressure and kidney strain.

- Reduce Sodium: Aim for <1500mg per day. Processed foods, canned soups, and salty snacks are the biggest culprits.

- Eat Potassium‑Rich Foods: Bananas, sweet potatoes, and beans help counteract sodium’s effect on blood pressure.

- Stay Active: At least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic exercise weekly improves vascular elasticity.

- Maintain a Healthy Weight: Every 5kg lost can drop systolic pressure by 5-10mmHg.

- Limit Alcohol: No more than two drinks per day for men, one for women.

- Quit Smoking: Tobacco narrows arteries and spikes blood pressure spikes instantly.

Medications That Protect the Kidneys

When lifestyle alone isn’t enough, doctors turn to drugs that both lower pressure and shield the kidneys.

- ACE Inhibitors: ACE inhibitors block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, easing arterial tone and reducing proteinuria.

- ARBs (Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers): Offer similar benefits for patients who can’t tolerate ACE inhibitors.

- Thiazide Diuretics: Help the kidneys excrete excess sodium and water, lowering volume‑related pressure.

- Calcium Channel Blockers: Relax arterial smooth muscle; useful in combination therapy.

Choosing the right regimen often depends on other health issues, especially diabetes.

Managing Co‑existing Conditions

Two conditions exacerbate the hypertension‑kidney loop:

- Diabetes: High blood sugar damages the glomeruli similarly to pressure. Managing glucose (HbA1c <7%) cuts CKD risk by 30%.

- Obesity: Excess fat raises cardiac output and activates the RAS. Weight‑loss programs can drop systolic pressure by 10-15mmHg.

When both hypertension and diabetes are present, a combined approach-tight blood pressure control (<130/80mmHg), aggressive glucose management, and kidney‑protective meds-offers the best chance to preserve kidney function.

Quick Takeaways

- High blood pressure damages the kidney’s filtering units (glomeruli) through arteriosclerosis, protein leakage, and nephron loss.

- Early detection via urine albumin and eGFR can catch damage before symptoms appear.

- Cut sodium, boost potassium, stay active, and keep a healthy weight to lower pressure naturally.

- ACE inhibitors or ARBs are the first‑line drugs that protect both heart and kidneys.

- Control diabetes and obesity simultaneously for the strongest defense against CKD.

Comparison Table: Hypertension Stages vs. CKD Stages

| Stage | Blood Pressure Range (mmHg) | eGFR Range (mL/min/1.73m²) | Typical Symptoms | Primary Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated / Stage1 | 120‑129 / <130 | >90 (Normal) | Usually none | Lifestyle changes, monitor |

| Stage2 Hypertension | 130‑139 / 80‑89 | 60‑89 (Mild CKD possible) | Fatigue, mild edema | ACE/ARB + lifestyle |

| Stage3 Hypertension | ≥140 / ≥90 | 30‑59 (Moderate CKD) | Visible swelling, decreased urine | Combination therapy, stricter diet |

| Stage4‑5 CKD | Often ≥150 | <30 (Severe CKD) | Uremic symptoms, anemia | Nephrology referral, possible dialysis |

Action Checklist for Patients with Hypertension

- Measure blood pressure at home at least twice weekly.

- Get a urine albumin test and eGFR every 12 months (more often if you have diabetes).

- Limit daily sodium to <1500mg; read nutrition labels.

- Take prescribed ACE inhibitor or ARB exactly as directed.

- Schedule follow‑up visits to adjust medication based on lab results.

- Adopt a DASH‑style eating plan (lots of fruits, veg, low‑fat dairy).

- Stay active-walk, bike, or swim for at least 30 minutes most days.

- Track weight; aim for a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can high blood pressure cause kidney failure on its own?

Yes. Persistent hypertension narrows and scars the glomeruli, reducing filtration. Without treatment, the damage can progress to end‑stage renal disease.

Is protein in urine always a sign of kidney disease?

Not always. Acute fever or intense exercise can raise urine protein temporarily. However, consistent micro‑albumin (>30mg/g) in a hypertensive patient usually indicates early kidney damage.

Do ACE inhibitors work for everyone?

Most people benefit, but some develop a persistent cough or elevated potassium levels. In those cases, an ARB is a good alternative.

How often should I get my eGFR tested?

If you have controlled hypertension without other risk factors, an annual test is sufficient. Add a test whenever medication changes or if you develop diabetes.

Can dietary changes reverse kidney damage?

Early damage (stage1‑2 CKD) can stabilize or improve with strict blood pressure control and a low‑protein, low‑sodium diet. Later stages usually require medical management and possibly dialysis.

maurice screti

One must appreciate the exquisite interplay between hemodynamic forces and renal microarchitecture, a relationship that the article elegantly outlines yet scarcely does justice to the depth of physiological nuance involved. The glomerular filtration barrier, composed of endothelial cells, basement membrane, and podocytes, is exquisitely sensitive to shear stress, and chronic elevation of systolic pressure inexorably leads to endothelial dysfunction. When the intravascular pressure persistently exceeds the autoregulatory set point, the afferent arterioles undergo maladaptive remodeling, culminating in luminal narrowing and hyperfiltration of the remaining nephrons. This hyperfiltration paradoxically accelerates nephron loss, a phenomenon that can be traced back to the seminal studies of Brenner in the 1980s. Moreover, the renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone system (RAAS) serves not merely as a regulator of systemic blood pressure but as a potent local modulator of intrarenal hemodynamics, fostering angiotensin II‑mediated vasoconstriction and pro‑fibrotic signaling. Angiotensin II also upregulates transforming growth factor‑beta, which orchestrates extracellular matrix deposition, thereby stiffening the glomerular capillary walls. Consequently, proteinuria emerges as the harbinger of glomerular injury, reflecting the breach of the filtration barrier's size-selective properties. The article’s risk calculator, while user‑friendly, must be contextualized within this broader pathophysiological framework; the point system oversimplifies a continuum of risk that is modulated by genetic predisposition, salt intake, and concomitant comorbidities such as diabetes. Lifestyle interventions, particularly sodium restriction and aerobic exercise, have been shown in randomized trials to attenuate RAAS activation, thereby mitigating the trans‑glomerular pressure gradient. Pharmacologically, ACE inhibitors and ARBs confer renoprotective benefits beyond mere blood pressure reduction, a fact that should be emphasized to clinicians counseling patients. In addition, emerging therapies targeting endothelin receptors hold promise for curbing the progressive scarring of renal tissue. Regular monitoring of eGFR and urinary albumin‑to‑creatinine ratio remains indispensable, as early detection permits timely therapeutic adjustments before irreversible fibrosis ensues. One cannot overstate the importance of patient education; many individuals remain blissfully unaware that a seemingly innocuous elevation of blood pressure can sow the seeds of chronic kidney disease over decades. Ultimately, a comprehensive approach that integrates vigilant screening, tailored pharmacotherapy, and sustained lifestyle modification constitutes the most effective bulwark against hypertension‑induced renal decline.

Abigail Adams

From a clinical standpoint, the article adeptly highlights the triad of hypertension, proteinuria, and eGFR decline, which constitute the cornerstone of CKD surveillance. It is imperative that primary care providers not only target a BP <130/80 mmHg but also prioritize RAAS blockade in patients exhibiting micro‑albuminuria, as evidence suggests a 30% reduction in progression to end‑stage renal disease. Moreover, the integration of lifestyle counseling-particularly sodium restriction to <1,500 mg/day-cannot be overstated.

Belle Koschier

I really appreciate how this piece breaks down the mechanisms without drowning us in jargon. The step‑by‑step explanation of how high pressure damages the glomeruli makes it clear why regular BP checks are so vital. Also, the reminder to get a urine albumin test is something many folks overlook, so thanks for that practical tip!

Allison Song

Considering the kidney as a delicate filtration system, it is philosophically intriguing to view hypertension as an external force that distorts the inner harmony of bodily functions. When the equilibrium is disrupted, the cascade of compensatory mechanisms-RAAS activation, sodium retention-reflects a deeper struggle for homeostasis. This underscores the importance of viewing blood pressure not just as a number, but as a symptom of systemic imbalance.

Joseph Bowman

Honestly, everyone’s quick to blame pharma for high blood pressure, but the real culprits are hidden-like the subtle mineral additives in processed foods and the covert data‑collection methods that push us toward a sedentary lifestyle. If you look beyond the obvious, you’ll see a network of interests that keep us hooked on medication while our kidneys silently suffer.

Singh Bhinder

I’m curious about the exact threshold where the RAAS system flips from protective to damaging. Is there a specific systolic value beyond which the renin‑angiotensin cascade becomes irreversible, or does individual genetics play a bigger role? Some clarification would help people gauge their personal risk.

Kelly Diglio

Thank you for the thorough overview. It’s reassuring to see clear guidance on both lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic options. Consistent monitoring of blood pressure, urine albumin, and eGFR can truly make a difference in catching early kidney damage before it escalates.

Carmelita Smith

Great summary! 😊

Liam Davis

Nice points!; I’d add that staying hydrated and limiting caffeine can also support kidney health; regular check‑ups are key; 👍

Arlene January

Let’s keep the momentum going, folks! Remember, every small step-like swapping out salty snacks for fresh fruit-adds up. Your kidneys will thank you, and you’ll feel more energetic in the long run!

Kaitlyn Duran

Just wondering, does the calculator factor in race or ethnicity? I’ve heard there can be differences in CKD progression.

Terri DeLuca-MacMahon

💡 Pro tip: Pair your BP meds with a DASH diet-lots of veggies, whole grains, and low‑fat dairy. It’s a win‑win for heart and kidneys! 🌱👍

gary kennemer

From a practical perspective, I’d suggest setting a monthly reminder to log your BP readings in a spreadsheet; trends become evident faster, and you can share precise data with your physician during visits.

Payton Haynes

They don’t tell you that the big pharma pushes the high‑BP drugs so they can keep us buying their stuff while our kidneys get damaged. Wake up!

Earlene Kalman

These articles are always the same.

Brian Skehan

Honestly, I’m not convinced this calculator does much. Most of us won’t even follow the advice anyway, so it’s just another pointless tool.