Facing pregnancy while living with Sickle Cell Anemia is a unique journey. Hormonal shifts, increased blood volume, and the stress of gestation can amplify the classic sickle‑cell crises, yet with the right preparation you can protect both your health and your baby’s development. This guide walks you through the science, the risks, and the practical steps you need to take so you feel confident from the first trimester to postpartum.

What Is Sickle Cell Anemia?

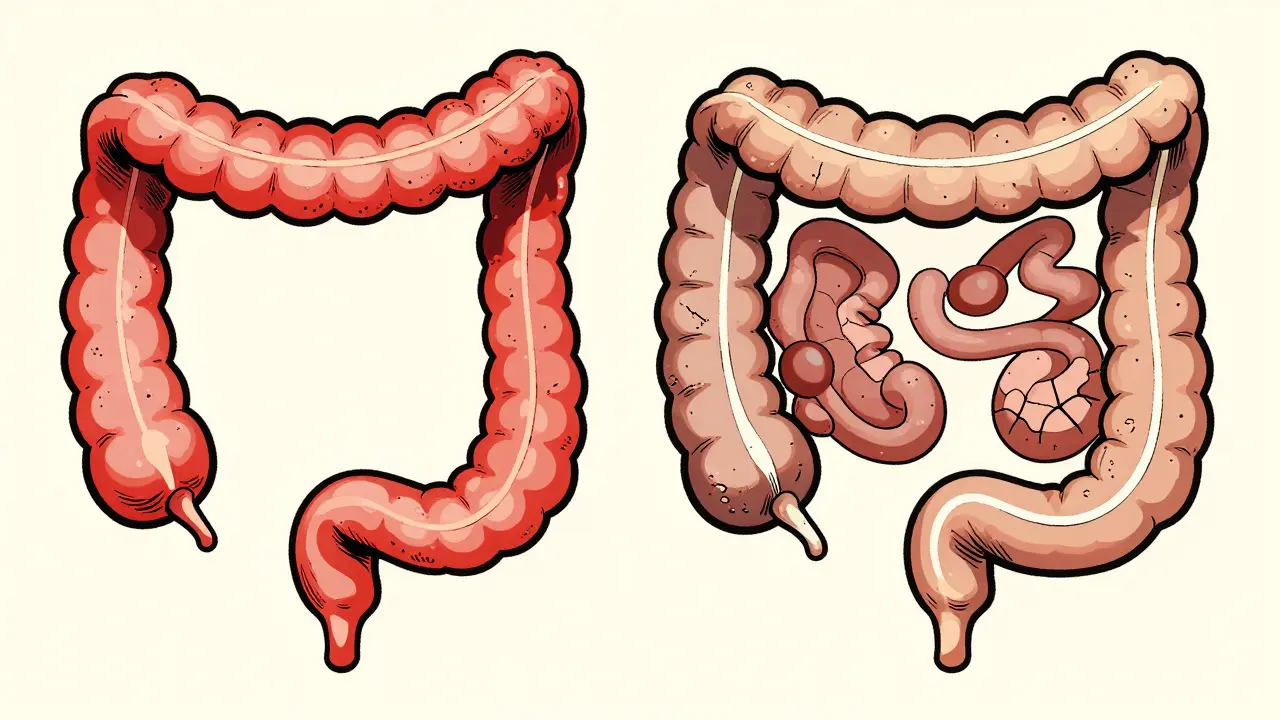

Sickle Cell Anemia is a hereditary blood disorder caused by a mutation in the beta‑globin gene (HBB). The abnormal hemoglobin (HbS) forces red blood cells to assume a rigid, crescent shape that can block small vessels, leading to pain episodes, organ damage, and chronic anemia. Worldwide, about 300,000 babies are born with the disease each year, with the highest prevalence in sub‑Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and parts of the United States.

Pregnancy and Its Impact on Sickle Cell

When you add Pregnancy into the mix, your circulatory system works overtime. Blood volume expands by roughly 40‑50 %, and oxygen demand rises to support the growing fetus. For someone with sickle‑cell disease, these changes raise the likelihood of vaso‑occlusive crises, infections, and complications such as pre‑eclampsia. On the flip side, careful monitoring can significantly reduce risks, and many women with sickle cell successfully deliver healthy infants.

Key Risks by Trimester

| Trimester | Primary Risks | Management Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| First (0‑13 weeks) | Increased vaso‑occlusive episodes, early miscarriage risk | Baseline blood work, start folic acid 4 mg/day, avoid dehydration, schedule hematology consult |

| Second (14‑27 weeks) | Growth restriction, pre‑eclampsia, infection susceptibility | Monthly ultrasounds, blood pressure monitoring, prophylactic penicillin if splenectomy history, careful pain‑management plan |

| Third (28‑40 weeks) | Pre‑term labor, acute chest syndrome, delivery complications | Plan for early delivery at 38 weeks if stable, transfusion protocol for high‑risk cases, coordinate with maternal‑fetal medicine team |

Preparing for Pregnancy

- Genetic counseling: Confirm your genotype (e.g., SS, SC, Sβ⁰) and discuss partner testing. If your partner carries the sickle gene, there is a 25 % chance of having a child with sickle cell disease.

- Pre‑conception health check: Get a full blood panel, iron studies, and a cardiopulmonary assessment. Baseline hemoglobin, reticulocyte count, and organ function tests guide future interventions.

- Vaccinations: Ensure you’re up to date on influenza, pneumococcal, and COVID‑19 vaccines. Infections can trigger crises.

- Medication review: Discontinue teratogenic drugs (e.g., certain antineoplastic agents). Discuss safe alternatives for pain control, such as acetaminophen, and whether to continue hydroxyurea (usually stopped before conception).

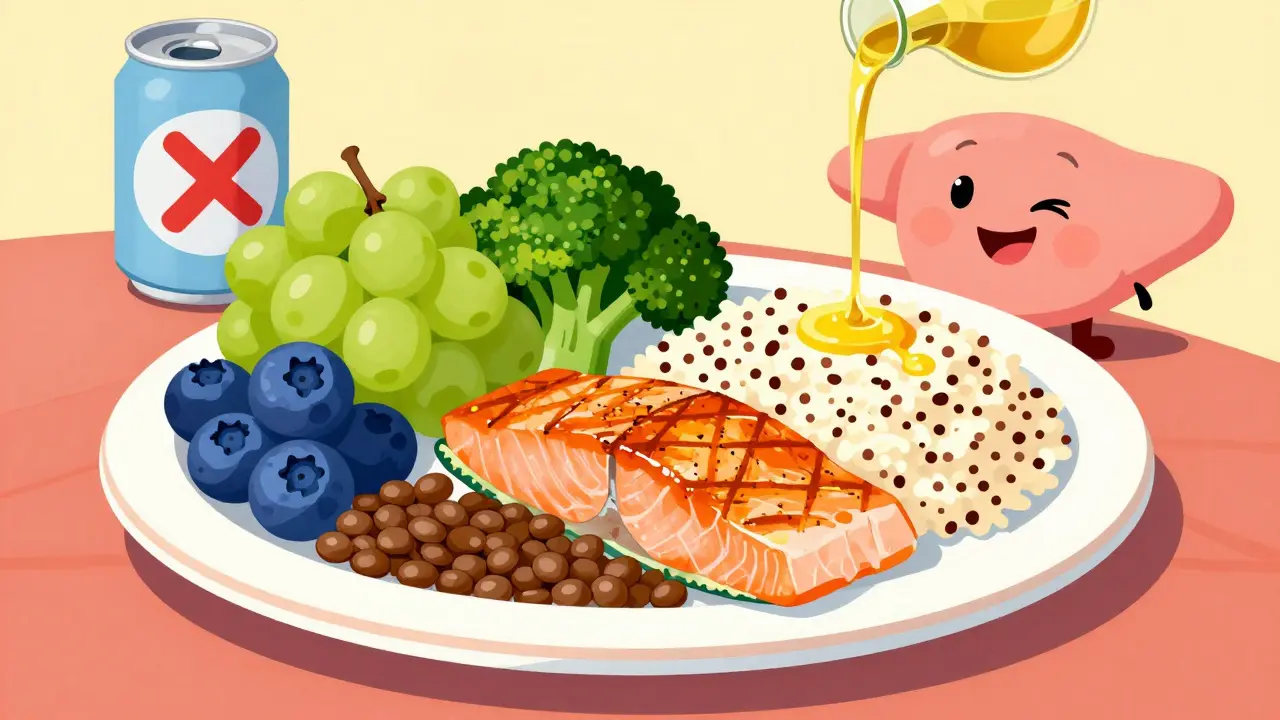

- Nutrition and hydration: Aim for at least 2‑3 L of fluid daily and a diet rich in folic acid, iron, and vitamin D.

Managing Health During Pregnancy

Once you’re pregnant, the focus shifts to vigilant monitoring and timely interventions.

- Regular hematology visits: Schedule appointments every 4‑6 weeks. Your doctor will track hemoglobin levels, assess organ function, and adjust treatment plans.

- Transfusion therapy: For women with a history of severe crises or when fetal growth falters, exchange transfusion can reduce HbS concentration below 30 %. This lowers the chance of vaso‑occlusion and improves oxygen delivery.

- Pain management: Non‑opioid options (acetaminophen, low‑dose NSAIDs in the first two trimesters) are first‑line. If opioids become necessary, use the lowest effective dose and involve a pain specialist.

- Infection prevention: Prompt treatment of urinary tract infections or respiratory illnesses is critical. Carry a rapid‑response plan for fever >38 °C.

- Blood pressure tracking: Sickle cell patients have a higher risk of pre‑eclampsia. Home blood pressure cuffs and weekly prenatal visits help catch early signs.

Delivery Planning

Most women with sickle cell can have a vaginal delivery, but the mode of birth should be individualized.

- Timing: Aim for 38‑39 weeks if maternal health is stable; earlier delivery may be indicated for worsening anemia or a rise in HbS%.

- Location: Deliver at a tertiary center with a dedicated maternal‑fetal medicine unit and a hematology team on standby.

- Labor analgesia: Epidural anesthesia is generally safe and can reduce the stress‑induced sickling during labor.

- Transfusion protocol: Many experts recommend a pre‑delivery exchange transfusion for women with a history of severe crises or if HbS% remains high.

Postpartum Care

The first six weeks after birth are a vulnerable window. Hormonal shifts can trigger new pain episodes, and breastfeeding mothers need to consider medication safety.

- Continue close follow‑up: See your hematologist within two weeks of delivery, then monthly for the first three months.

- Hydroxyurea considerations: This drug is safest to resume only after breastfeeding ends, unless the benefits outweigh risks-in which case a low‑dose approach may be approved.

- Iron supplementation: Assess iron stores; excessive iron can be harmful, especially if you received multiple transfusions.

- Contraception counseling: Discuss reliable, non‑hormonal methods if you wish to delay another pregnancy, as hormonal contraceptives can affect blood viscosity.

Common Myths Debunked

- Myth: Women with sickle cell cannot have children.

Fact: With modern care, over 80 % of pregnancies result in live births. - Myth: All pain medication is unsafe during pregnancy.

Fact: Acetaminophen and carefully monitored opioids are permissible; your doctor will tailor the regimen. - Myth: Hydroxyurea must be stopped forever.

Fact: It is often paused before conception and restarted postpartum if needed.

Checklist for Expectant Mothers with Sickle Cell

- Confirm partner’s sickle‑cell status.

- Schedule pre‑conception hematology appointment.

- Update all vaccinations.

- Start folic acid 4 mg daily.

- Maintain hydration - 2‑3 L of water daily.

- Arrange monthly blood work and ultrasound monitoring.

- Discuss transfusion plan with your obstetric team.

- Prepare a rapid‑response plan for fever or severe pain.

- Identify a tertiary delivery center with sickle‑cell expertise.

- Plan postpartum follow‑up and contraception options.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I have a natural vaginal delivery?

Yes, most women with sickle cell can deliver vaginally. The decision depends on your anemia status, any previous complications, and whether a pre‑delivery transfusion is planned.

Is it safe to breastfeed while on sickle‑cell medication?

Acetaminophen and most antibiotics are compatible with breastfeeding. Hydroxyurea is usually avoided during lactation because it passes into milk; discuss alternatives with your doctor.

What should I do if I develop a fever?

Contact your obstetrician or hematology team immediately. Fever can precipitate a sickle‑cell crisis; prompt antibiotics or antipyretics are often required.

Do I need extra vitamin supplements?

Folic acid 4 mg daily is essential. Your doctor may also prescribe vitamin D and calcium, especially if you have bone‑density concerns.

How often should I be monitored?

Initial visits are every 4‑6 weeks, increasing to bi‑weekly in the third trimester. Ultrasound assessments are typically done monthly to track fetal growth.

Understanding the interplay between sickle cell anemia pregnancy and careful medical planning empowers you to navigate the challenges confidently. By staying informed, keeping hydrated, and maintaining a strong care team, you give both yourself and your baby the best chance at a healthy outcome.

Joe Moore

Yo folks, real talk – they’re hiding the real cure for sickle cell from pregnant women. The pharma giants are in cahoots with the government to keep you on endless pain meds while they cash in. Stay woke, keep your water intake high, and don’t trust the first doc who tells you “everything’s fine.” They’ll say it’s just “normal pregnancy symptoms,” but we know the hidden agenda. Remember, the vaccine schedules are a smokescreen for micro‑chips, not health care.

Drew Waggoner

The weight of every crisis feels like a stone lodged in my chest, and reading this guide only amplifies the dread. It’s hard to breathe when you think about another flare‑up during labor, and the constant monitoring feels like an endless parade of appointments. I wish there were a way to silence the relentless anxiety that follows each lab result. This knowledge is both a lifeline and a torture.

Matthew Miller

Hey powerhouse moms! Let’s channel that fierce energy into staying hydrated, scheduling those hematology visits, and crushing each trimester like a boss. You’ve got a superhero’s blood, and with the right plan you’ll turn every challenge into a victory dance. Keep shining, stay fierce, and let’s slay these sickle‑cell hurdles together!

Liberty Moneybomb

Oh my god, can you even imagine the drama of trying to give birth while your blood decides to turn into tiny icebergs? The whole medical establishment is clearly out to sabotage us, feeding us half‑truths while they hide the ultimate protocol – a secret transfusion regimen that they refuse to share. Every ultrasound feels like a ticking time bomb, and the nurse’s smile is just a mask for the hidden agenda. I’m calling out the shadowy board that decides who gets the safe delivery room and who gets left in the dark. Wake up, sisters!

Alex Lineses

For all expectant mothers navigating hemoglobinopathies, implementing a multidisciplinary care algorithm is paramount. Aligning obstetric ultrasound metrics with serial hemoglobin electrophoresis results enables proactive risk stratification. Initiate prophylactic penicillin in splenectomized patients per CDC guidelines, and consider exchange transfusion protocols when HbS fraction exceeds 30 %. Collaboration between Maternal‑Fetal Medicine, Hematology, and Neonatology ensures optimal perinatal outcomes. Remember, your care team functions as an integrated network-don’t hesitate to voice concerns during each visit.

Brian Van Horne

Your succinct summary eloquently captures the essential monitoring milestones for sickle‑cell pregnancies.

Norman Adams

Ah yes, because clearly the easiest solution is to simply ignore the labyrinthine pathophysiology and hope the fetus will perform a miracle on its own. One can almost hear the angels singing as we prescribe a generic painkiller and call it a day, while the underlying vaso‑occlusive cascade continues unabated. Truly, the hallmark of cutting‑edge medicine is the ability to pretend complexity doesn’t exist.

Margaret pope

You’ve nailed the checklist there it’s a solid roadmap for anyone dealing with sickle cell during pregnancy however remember to keep a personal log of symptoms and share it with your team regularly it makes a huge difference in early detection.

Karla Johnson

Navigating a pregnancy complicated by sickle cell anemia demands a level of vigilance that most expectant mothers can scarcely imagine.

From the moment conception is confirmed, the body embarks on a physiological marathon, expanding blood volume, altering oxygen transport, and reshaping hormonal landscapes.

These changes, while natural for a typical gestation, intersect with the pathophysiology of sickle cell in ways that amplify vaso‑occlusive risk.

Consequently, the first trimester becomes a critical window during which baseline hematologic assessments must be painstakingly documented.

A comprehensive panel including hemoglobin electrophoresis, reticulocyte count, and renal function tests provides the necessary foundation for individualized care plans.

Moving into the second trimester, fetal growth trajectories must be monitored at least monthly, as placental insufficiency can arise from microvascular obstruction.

Blood pressure surveillance is equally vital, since the confluence of sickle cell disease and pregnancy elevates pre‑eclampsia incidence beyond the general obstetric population.

Patients should be educated about early signs of infection, given that febrile episodes can precipitate a sickle crisis with alarming rapidity.

Prophylactic penicillin, when indicated, offers a shield against pneumococcal and other invasive pathogens that thrive in asplenic individuals.

Nutrition cannot be overstated; a daily intake of 2–3 liters of water, alongside folic acid supplementation of 4 mg, supports erythropoiesis and reduces sickling events.

When the third trimester approaches, interdisciplinary coordination becomes paramount, involving obstetricians, hematologists, anesthesiologists, and neonatologists.

A pre‑delivery exchange transfusion aimed at reducing HbS levels below 30 % has been shown in multiple studies to diminish both maternal and fetal complications.

The mode of delivery should be individualized; while many women can experience vaginal birth, a planned cesarean may be warranted for those with severe anemia or acute chest syndrome.

Post‑partum, the hormonal surge can reignite pain episodes, making prompt follow‑up within two weeks essential for adjusting therapy.

Breastfeeding considerations must also be addressed, as certain medications cross into milk and may affect the newborn.

In sum, the synergy of diligent monitoring, proactive transfusion strategies, and patient education forms the cornerstone of a successful pregnancy outcome for women living with sickle cell disease.

Tracy O'Keeffe

Well, if you think the mainstream protocol of scheduled exchange transfusions is the be all and end all, you’re simply buying into the medical establishment’s narrative. I’ve read clandestine reports that suggest a low‑dose hydroxyurea regimen might actually stabilize hemoglobin levels better than constant transfusions, yet no one dares to publish that. It’s almost theatrical how they parade around guidelines while ignoring off‑label successes. So, before you blindly follow the “official” checklist, consider the hidden data and the possibility that the safest path could be the uncharted one. Let’s not be sedated by consensus.

Albert Fernàndez Chacón

I hear you – juggling appointments, pills, and worrying about the baby can feel overwhelming. Remember to take a moment each day to breathe deeply and remind yourself that you’re doing the best you can. Your care team is there to help, so don’t hesitate to ask for clarification on anything that seems confusing.

Mike Hamilton

Life’s journey through a sickle‑cell pregnancy mirrors the ancient river that must carve its path through rugged stone; the water persists, finding new routes when the old ones are blocked. We must embrace this fluid resilience, allowing each trimester to teach us humility and strength. In the grand tapestry of exisistence, each heartbeat is a thread that weaves the story of survival, and our choices are the loom that shapes destiny.

Linda A

The existential weight of a sickle‑cell pregnancy is a silent storm, unseen yet profoundly felt. One must accept the quiet turmoil while moving forward.

Ayla Stewart

Your outline is thorough; I would add a note about the importance of mental health screening each trimester.

Poornima Ganesan

Let’s cut to the chase: most of the guidelines you’re following are borrowed from studies that excluded high‑risk populations, so they’re not a perfect fit for you. You need a personalized protocol that accounts for your specific genotype, previous crisis frequency, and organ function. Ignoring these nuances is akin to reading a cookbook and ignoring the allergy warnings. Demand a tailored plan from your hematologist; otherwise you’re gambling with both your life and your baby’s.